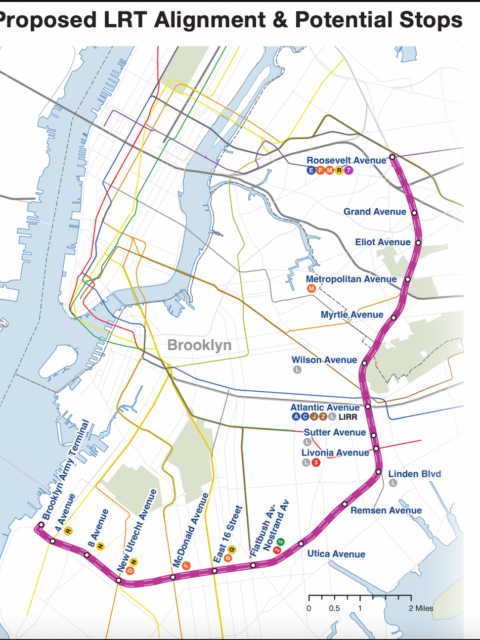

When the Interboro Express (IBX) was announced in January, 2022 by Gov. Kathy Hochul, it came as a welcome surprise to many who had been following the saga of the Triboro Line, a circumferential transit line connecting Brooklyn, Queens and the Bronx, first proposed by the Regional Plan Association in the mid 1990s. Running along the LIRR Bay Ridge Branch and over the Hell Gate Bridge, the Triboro Line was going to slash travel times between the outer boroughs, especially between the Bronx and Queens. But when the IBX was presented, many were shocked to see that no connections to the Bronx were included.

When asked about this, the MTA claimed that there was not enough capacity [PDF, pg. 2] on the Hell Gate Bridge to support the IBX as well as existing freight and passenger traffic. The MTA even claimed that if the IBX were to ever continue to the Bronx, it would need a new bridge. In 1925, a new East River Bridge might seem sensible, but in 2025 the idea seems as distant as landing men on the surface of Pluto. Given that the Hell Gate Bridge is far from operational capacity, why can’t the IBX use it to reach the Bronx?

Background

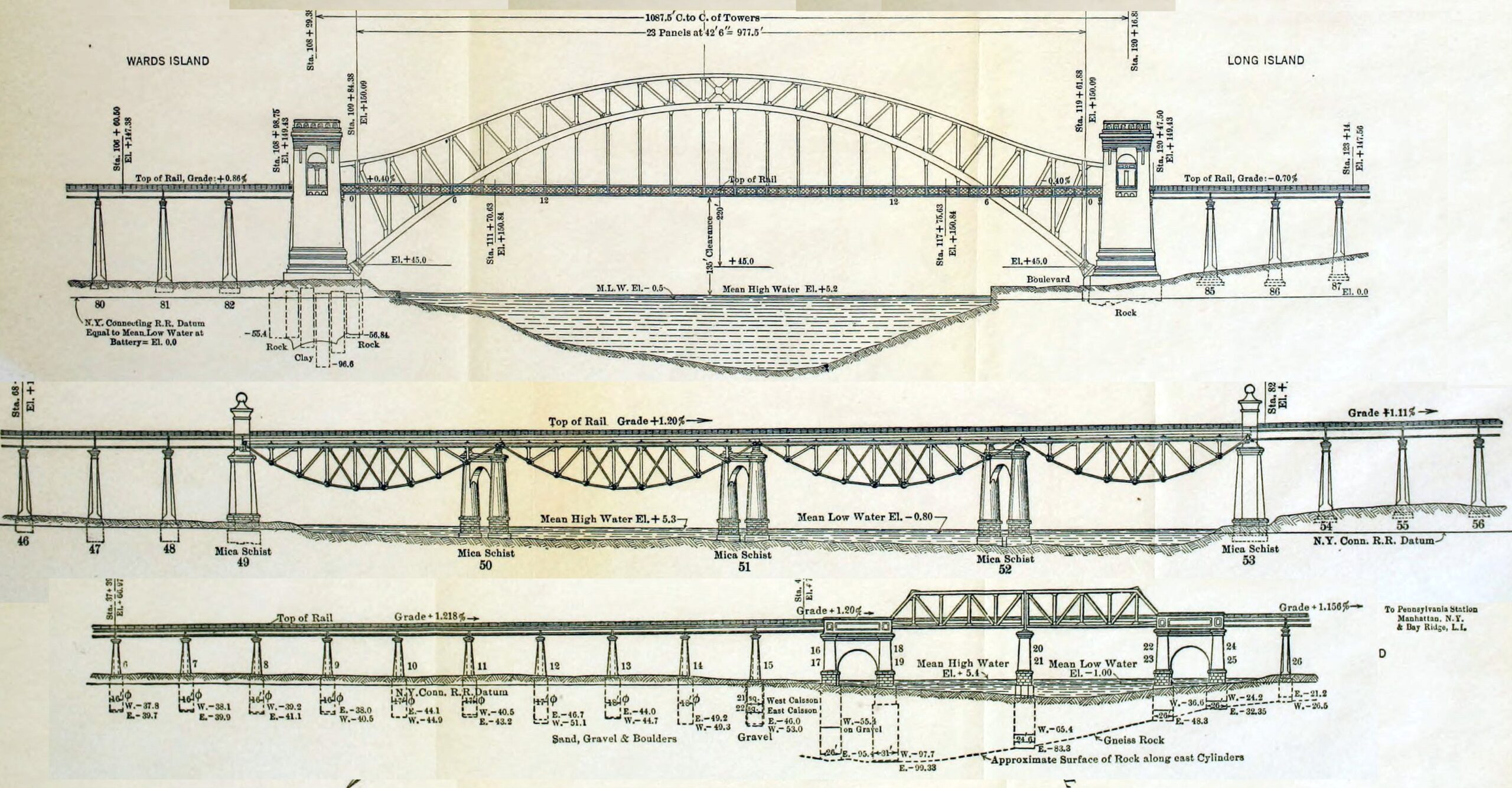

On the surface, the Hell Gate Bridge, with three active tracks and a fourth that could be easily reactivated, seems to have more than enough capacity. To understand why this might not be the case, we must first understand how the Hell Gate Bridge is used today, and what is planned for it tomorrow.

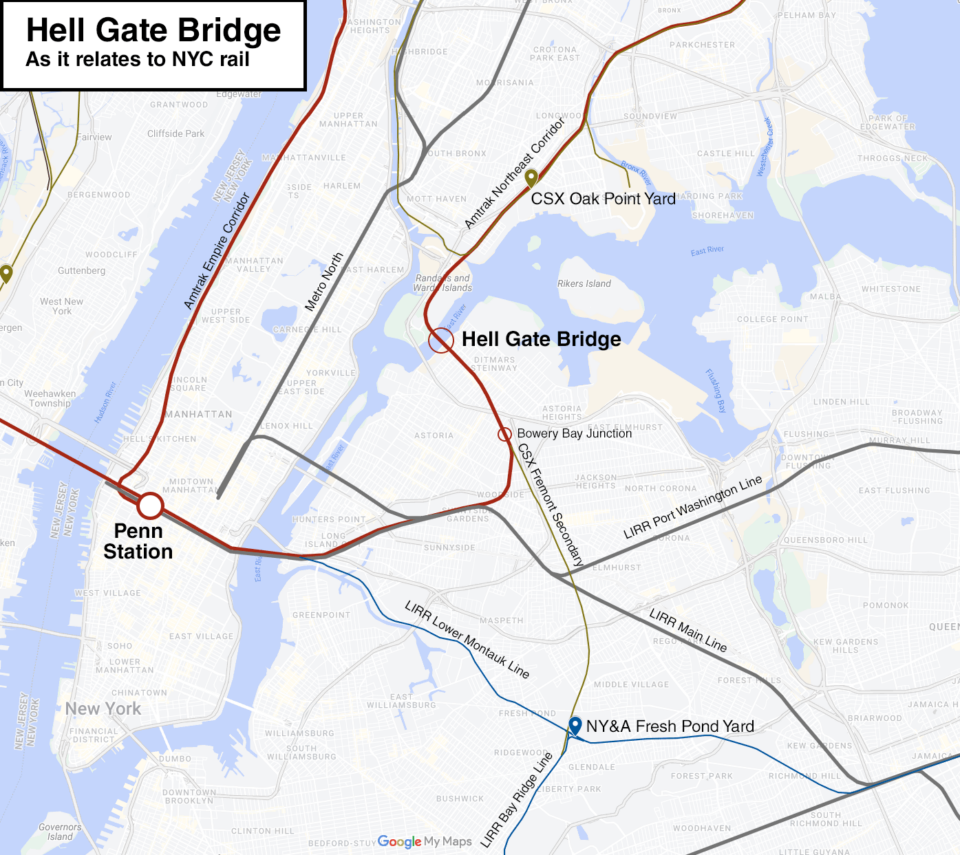

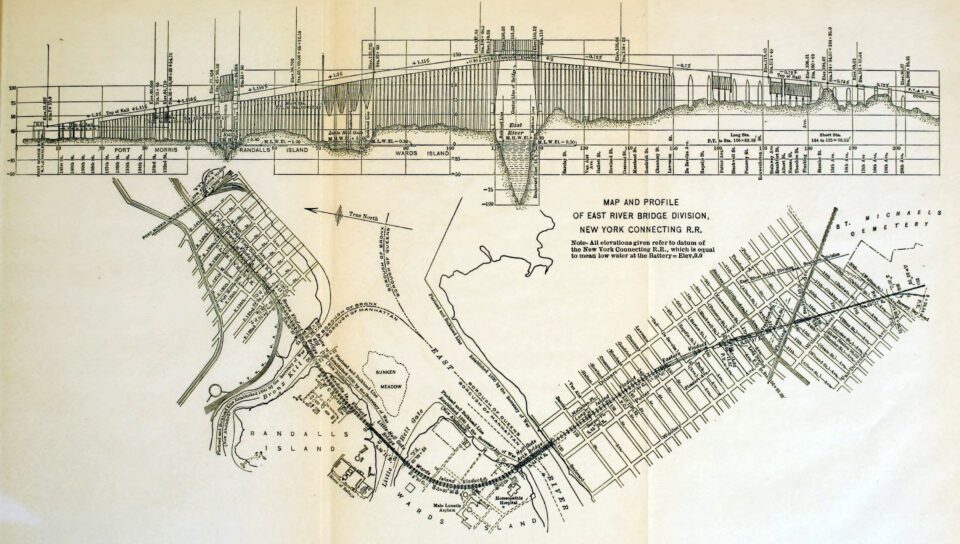

The Hell Gate Bridge was opened in 1912, built by the New York Connecting Railroad (which was co-owed by the Pennsylvania and New Haven Railroads). Since 1975, the bridge is owned by Amtrak. Built with four tracks, two for passenger service and two for freight, today Amtrak uses the bridge for its Northeast Corridor (NEC) regional and Acela trains. A third track is used for CSX (the fourth track was removed in the 1970s). CSX owns the Oak Point Yard at the base of the bridge in the Bronx, and the Fremont Secondary, a single track running off the bridge into Queens. The Fremont Secondary connects to the Fresh Pond Yard, and the LIRR Bay Ridge Branch south of there, which is owned by the LIRR (MTA).

When the Triboro Line was first proposed in the mid-1990s, the Hell Gate Bridge was only used by a few Amtrak NEC passenger trains, and a maybe-once-a-day freight train run by CSX. Amtrak has since increased service on the NEC, and is looking to increase service in the future. CSX currently runs between 1 and 3 freight trains per day over the bridge.

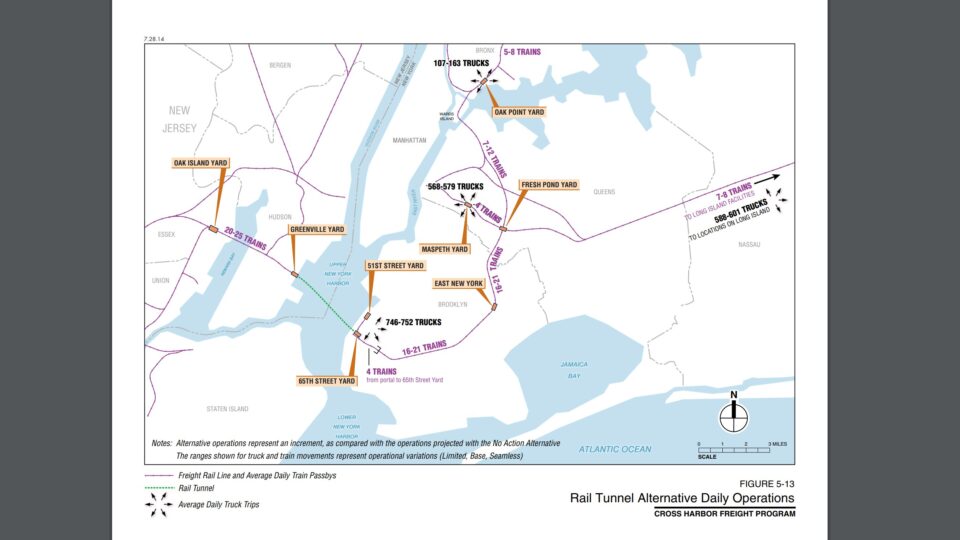

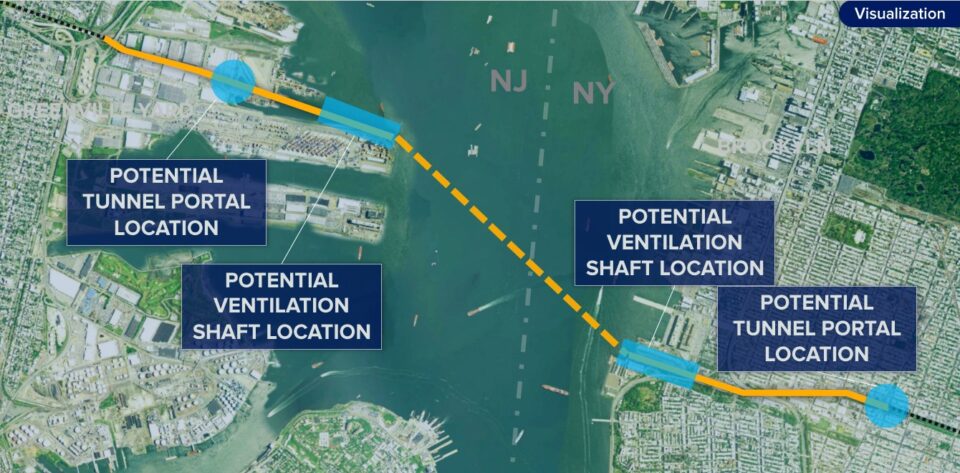

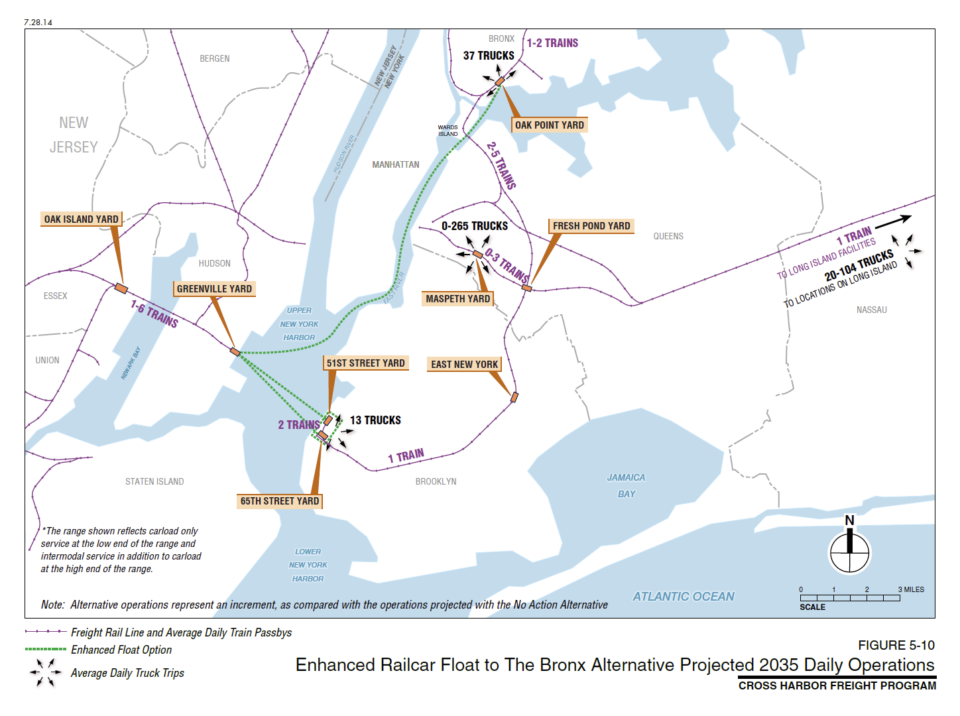

Freight traffic on the Bay Ridge Branch comes mostly from a car float that moves freight cars across New York Harbor on barges. Traffic has tripled in the last 30 years, and the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey (PANYNJ) has struck a deal with New York State to provide space along the IBX for future freight service. The PANYNJ is moving forward with a Tier II EIS for their Cross Harbor Rail Tunnel, which aims to connect the Greenville Yard in Jersey City, NJ with the Bay Ridge Branch in Brooklyn. The PANJNY projects up to 21 trains per day will use the tunnel, and up to 12 trains per day will cross the Hell Gate Bridge.

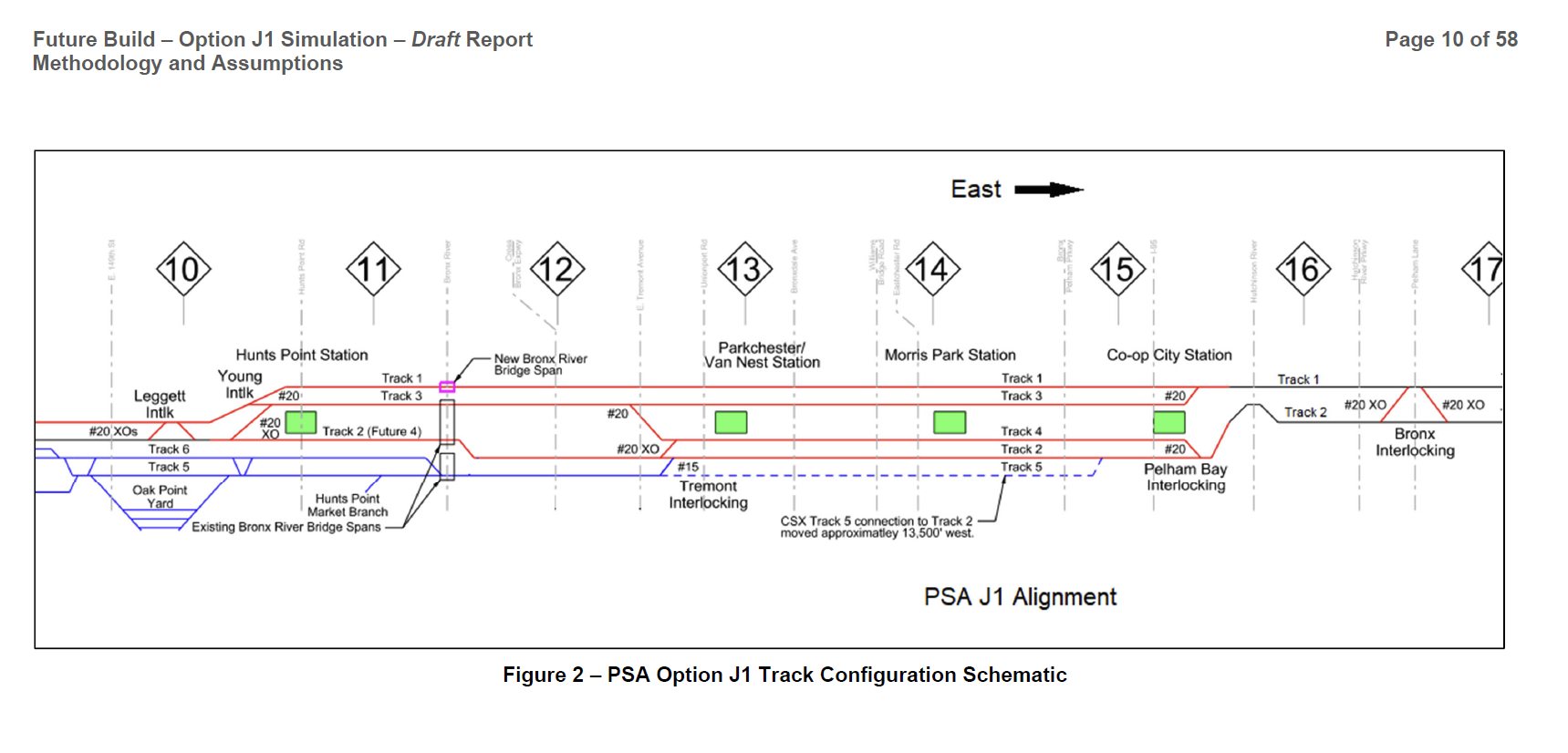

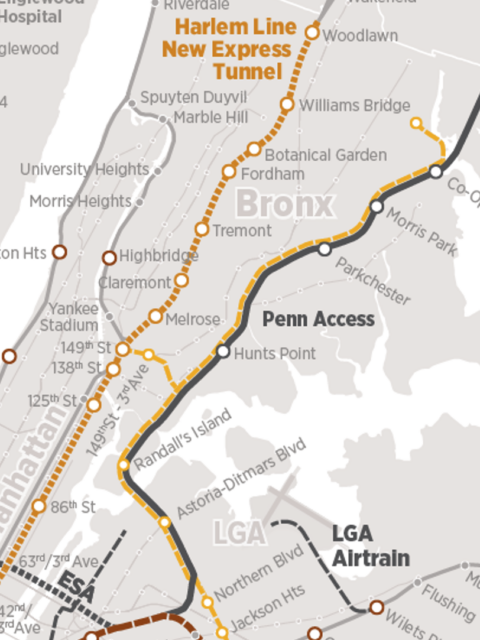

In the Bronx, the MTA is currently building out Penn Station Access (PSA) which will upgrade the NEC to allow for a new Metro North service serving Penn Station. PSA is being designed to so that each service is segregated: Amtrak trains will use the outer tracks and not stop, while Metro North will use the inner tracks and stop at island platform stations.

In their EIS for PSA [PDF], the MTA projects that once operational, 161 combined Metro North/Amtrak passenger trains per day will cross the Hell Gate Bridge. Broken down, there is an average of 3.3tph in either direction, though up to 6tph in peak directions. Trains will be scheduled around open slots at Penn Station and on the New Haven Line. PSA trains are planned to turn around at New Rochelle, so headways will be determined on when PSA trains can slip past through-trains between Grand Central Terminal and New Haven.

Freight

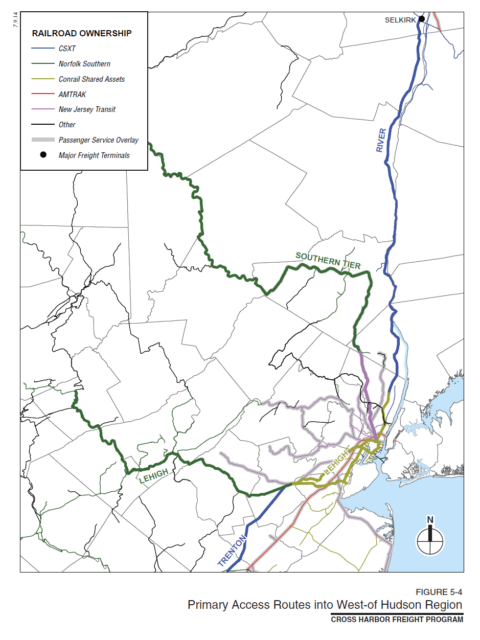

Most freight that comes into the New York region is destined to pass on through (most through the Port of Elizabeth). Rail freight arrives in New Jersey from the west and south via CSX and Norfolk Southern railroads. From the north, CSX runs freight down the west side of the Hudson River from the Selkirk Yard just outside of Albany. Norfolk Southern brings in freight from the south and west. In New Jersey, the freight is either moved to container ships, placed on trucks, or moved to rail yards. Within a certain zone in New Jersey, all freight is switched to Conrail Shared Assets railroad, a legacy carrier left over from the Conrail consolidation in the 1970s.

A small amount of freight runs down from Selkirk along the east side of the Hudson, along the Amtrak Empire Corridor and Metro North Hudson Line. This traffic ends at Oak Point Yard in the Bronx, at the foot of the Hell Gate Bridge. While CSX does have operation rights along the NEC, because of the high volume of passenger service on the line, freight into Connecticut is usually run from Selkirk through Massachusetts first, and then down into CT. Freight that runs over the Hell Gate Bridge is mostly destined for Long Island. Freight to and from Long Island is mostly trash, construction materials (like lumber or gravel), and beer.

The only traffic that crosses the harbor itself does so on barge floats run by the PANJNY. This operation is run as a relay between a number of small rail carriers at yards along the way. Beginning at the Greenville Yard in Jersey City, NJ, barges move the cars to the 65th St Yard in Sunset Park, Brooklyn, which sorts them. Next, the New York & Atlantic RR connects these cars and runs them to the Fresh Pond Yard in Queens. From here, CSX will take some trains over the Hell Gate Bridge, and the rest will be sent to Long Island over the LIRR. In the last half decade, the PANYNJ has invested heavily into this operation, with new barges that can carry more tonnage.

Mixing freight and passenger service is something that the United States is particularly bad at, even in the days of mass long distance train travel. Most Amtrak routes run on rail owed by private freight carriers. Legally, Amtrak always has the right-of-way on private lines. But in practice, Amtrak trains are routinely delayed by freight trains.

Freight trains are longer, heavier, and slower than the average passenger train. Freight trains do not run on tight schedules in the same way that passenger rail does. In a region with such high passenger rail volumes as New York, most freight traffic is segregated on their own tracks. While CSX owns its tracks on the west side of the Hudson, most of the tracks on the east side are owned by the MTA or Amtrak. Ultimately, Amtrak has the final say in who gets to use their bridge.

A freight rail tunnel under the harbor has been discussed in some way since the late 1800s. Due to the size of the project, it was always going to be massively expensive, whereas moving freight cars around the harbor on barges was relatively cheap. As freight shifted to trucks, new automobile bridges and tunnels were built to connect the region, and the need for a rail tunnel dwindled. But with the growth in freight and traffic over the last 30 years, the idea for a tunnel has come back. Calls for the tunnel have been championed by Congressman Jerry Nadler, and supporters claim that the tunnel will help take hundreds of trucks off of local crossing and roads.

This claim is somewhat debatable because, eventually, the containers on the rail cars will shift to the backs of trucks; Last-mile operations ultimately require this transfer. It’s that by building new transload facilities (where freight is moved from train to truck) within the city or on Long Island, trucks are making more local deliveries and fewer cross-regional deliveries. Frewer trucks criss-crossing the region is better for the roads, traffic, and the air. Moving more rail by freight doesn’t so much take trucks off of all roads, just key congested crossings.

Moving more freight through the region by rail is a stated policy goal of NYS DOT. DOT projects that in the next 25 years, the region will see an increase of 34% in “commodity flow volume”, and most of this traffic will be brought in on the backs of trucks. To keep our roads from being a giant parking lot of trucks, the city and state will invest in transload facilities over the next decade. Located mostly in Brooklyn, Queens, and Long Island, these transfer facilities will keep trucks out of Manhattan and congested regional crossings.

The real improvement that a tunnel offers is in efficiency. Instead of taking apart a freight train in New Jersey and having multiple operators move the cars around, then reassemble the train in New York (which can take up to two days), with a tunnel, a single operator can take one train from beginning to end. If the same operator were to do that today, it could take up to 48 hours to run up to Selkirk and back down. Freight that today must wait days to be moved across the region wastes space for trains further afield. Moving freight through the region at a fraction of the time speeds up traffic all the way from Chicago and Virginia.

IBX Planning

The IBX is planned to run along the Bay Ridge Branch and a small portion of the CSX-owned Fremont Secondary from Bay Ridge to Jackson Heights. The MTA is designing the IBX not to impede future freight rail growth. The ROW varies in width: most of the route is at least 2-tracks wide, while other portions are 4-tracks or more. To provide at least three tracks along the entire route (two for IBX, one or more for freight), the MTA plans to cut back embankment walls and rebuild bridge abutments where the ROW is most narrow.

Based on a preliminary feasibility study, the MTA chose light rail vehicles (LRV) to run along the IBX. While light rail is a bit of a catch-all term, here the MTA is talking about low-floor vehicles that are capable of running on both a dedicated ROW and in the street. While LRVs are new to the MTA ecosystem, they are currently being run on the Hudson Bergen Light Rail in Jersey City. Light rail stations are able to have cheaper, low level platforms for ADA accessibility, where CR trains require more expensive, high level platforms.

The MTA primarily runs conventional rail (CR) on Metro North and the LIRR. The FRA classifies rail types in a more structured way than the average person. To the FRA, even the subway is considered light rail, as by their definition, conventional rail is rail that is made up of train cars that are heavy enough to withstand hitting a freight train. Neither a subway car nor LRV are heavy enough, so these trains can not run on the same tracks as the LIRR, Metro North, or freight rail.

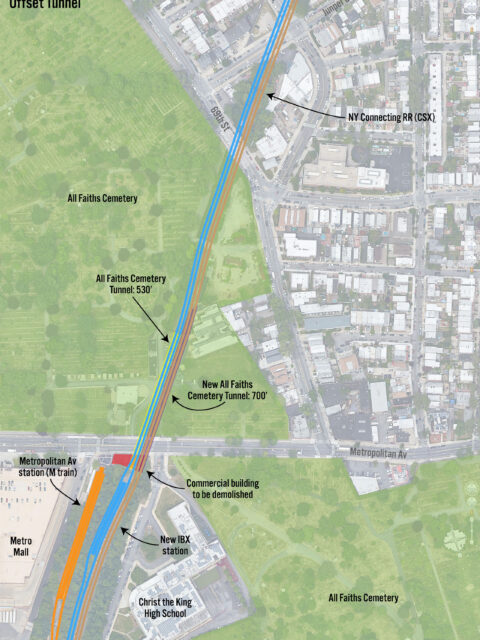

LRVs were also chosen because they could fit in the narrow East NY Tunnel (which is too narrow for wider M9 or B-Division subway car bodies), and so that they could run along the street on a short section in Middle Village to avoid building a second tunnel through the All Faiths Cemetery. For the East NY Tunnel, the issue was that using larger rail cars that run on third-rail power requires adding a bench wall along the sides of the tunnel. These walls are so that workers can pass through the tunnel away from the third-rail, as well as when passengers need to be evacuated in case of an emergency. By using overhead catenary wires, workers and passengers can walk along the tunnel floor instead.

Famously, the MTA did not consult the cemetery while it was working on the IBX Planning study. Because of this, their consultants drew up plans for a potential 1-mile-long tunnel for CR that would dive well below the existing tunnel. Alternatively, if LRVs were to be adopted, the cemetery was to be bypassed via street running on local roads. While the MTA was clearly leaning towards LRVs, the street-running concept cemented the idea.

In a previous post, I looked at why this was such a disastrous decision. The MTA held a number of public meetings to elicit feedback, and judging from the ones I attended, the street running was the number one problem people brought up. After this backlash, the MTA wisely went back and took another look at the tunnel. President of MTA Construction & Development Jamie Torres-Springer announced in late 2024 that the MTA had changed course and were considering a tunnel through All Faiths Cemetery.

While the MTA has not said anything publicly, there are many that believe that a major reason that the MTA wants to go with LRVs is that they can be autonomous vehicles, or at the very least One Person Train Operation (OPTO). Systems in Paris, China and Montreal have gone this route, which keeps labor costs to a minimum.

CR may fall under the same labor agreements as the LIRR and Metro North have now, meaning that they will have to be staffed by at least two, if not more, conductors, greatly adding to the operation costs. It should go without saying, but mixing automated passenger rail with non-automated rail (Amtrak and Metro North) on the same tracks is not feasible. So should the IBX be built as an automated LRV, it would be very costly to convert it to the more labor-intensive CR.

Hell Gate Scenario

This begs the question, is it possible to develop an IBX scenario that can use the Hell Gate Bridge in the future? The Hell Gate Bridge, and its approach viaducts in the Bronx and Queens, is 4-tracks wide. Today, only three tracks are active, two used for Amtrak and one for CSX. If the IBX were to use low-floor CR train cars that are FRA-rated to run on freight tracks, would it be possible to use the existing Hell Gate tracks to extend the IBX to the Bronx?

Presently, the bridge sees at most 3 Amtrak trains an hour (usually once an hour after peak times), and one to three CSX freight trains a day. However, when PSA is operational, the passenger tracks will see double the service. This equates to an average of one passenger train (Metro North or Amtrak) every 10 min. The IBX is planned to have a peak frequency of 12tph, with trains running every 5 min at peak times. On paper, the combined frequencies of IBX, Metro North, and Amtrak should be manageable at 18tph with two tracks. In practice, the frequencies of all three services won’t be harmonious due to the fact that Metro North and Amtrak will be scheduled around Penn Station slots.

If all three services are run together on the existing passenger tracks, there will be frequent times when one of the services is delayed. Having a buffer of a few minutes is fine at longer intervals, as is very often the case with Metro North. But with more frequent headways, the IBX can’t afford to lose that much time. Delays will not be localized in New York, but would ripple up and down the NEC. A simple solution may be to find the most common instances where trains conflict and short turn IBX trains at Roosevelt Ave. The IBX should be capable of at least 24tph on modern signal systems, so the MTA is starting with 12tph means they will gauge demand and add service if necessary. Short turning IBX trains would permanently reduce service on any Bronx branch of the IBX, which would be seen as a non-starter. This also means that any Amtrak or Metro North service would be capped as well.

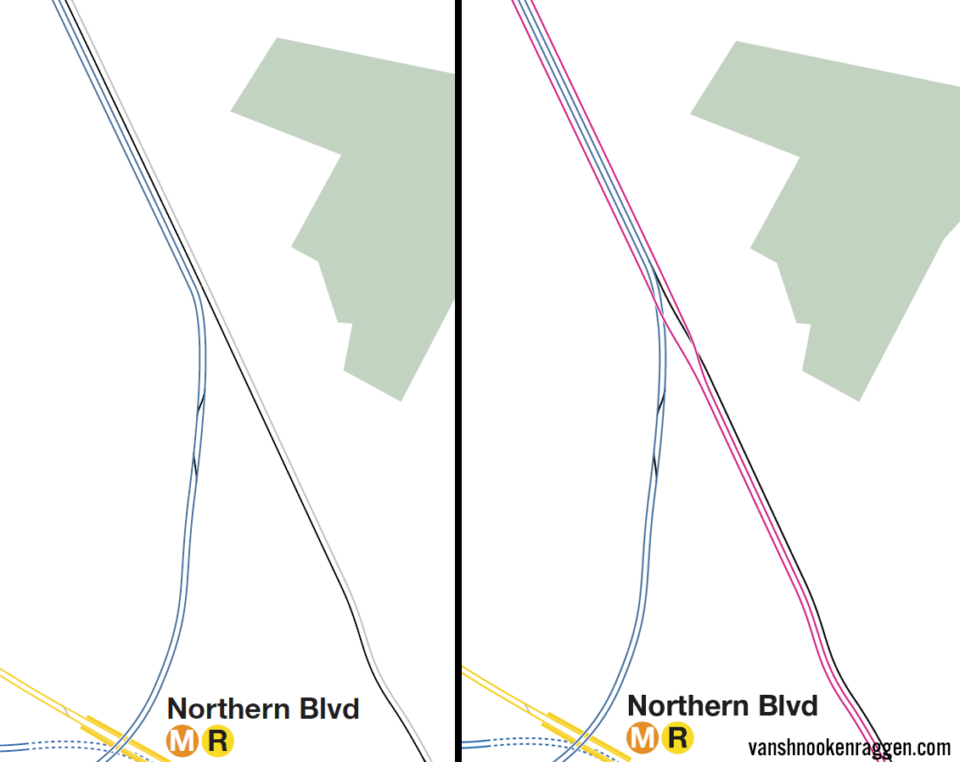

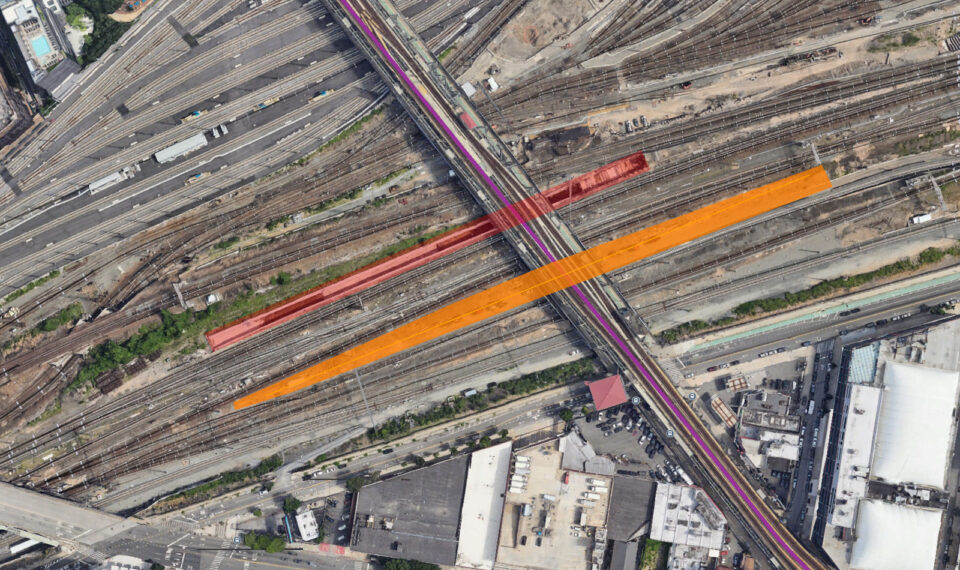

If the IBX is to use the Hell Gate Bridge, all four tracks must be used. The outermost tracks will be used exclusively for IBX, while the inner tracks will be for the other services. This allows the IBX to run traditional LRVs, or even automated trains, without scheduling problems. To facilitate this, the tracks at Bowery Bay Junction (where the NEC meets CSX and IBX in Astoria) need to be realigned. The existing NEC tracks shifted to run down the middle of the bridge. Both tracks of the IBX would flyover the NEC and Fremont Secondary tracks.

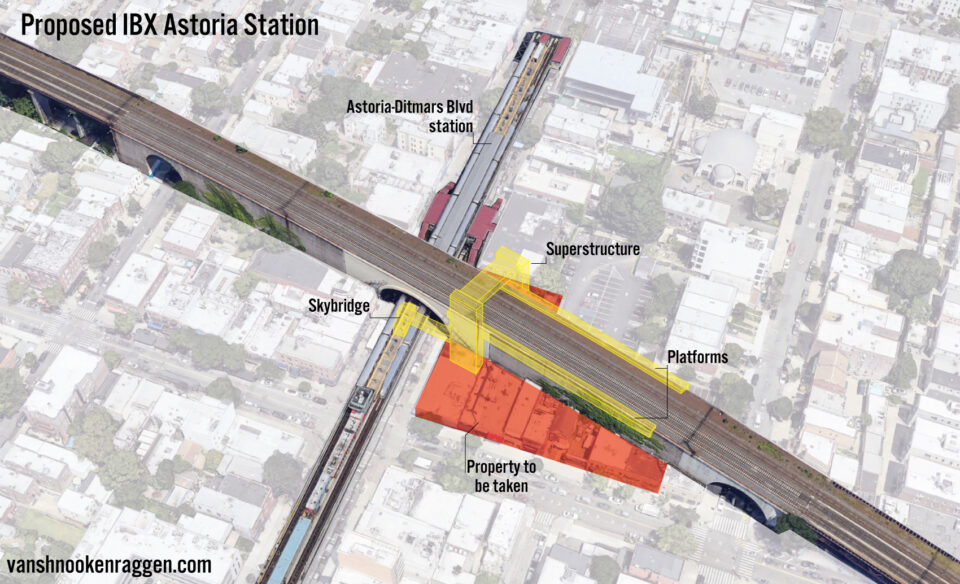

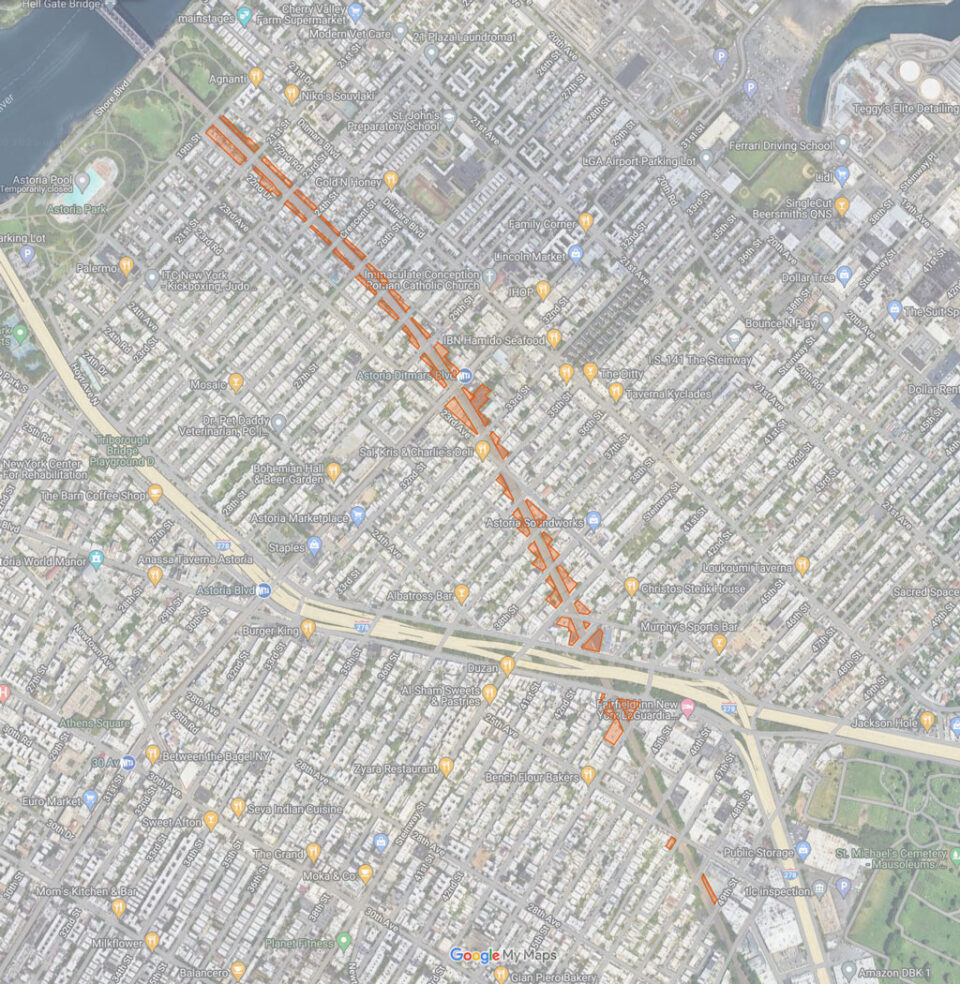

The Hell Gate Bridge approach viaduct rises over Astoria and crossed the NYCT Astoria Line (N/W trains) right above the Ditmars Blvd terminal. No station on the Hell Gate was ever planned for Astoria, as the bridge opened before the subway. Any new station will require expensive rehabilitation and adaptation of the structure, which is a masonry arch span in poor condition. Station platforms would have to hang off either side of the structure. The homes and businesses, which are built directly up against the viaduct, need to be demolished for construction and vertical access. The station would only serve the IBX.

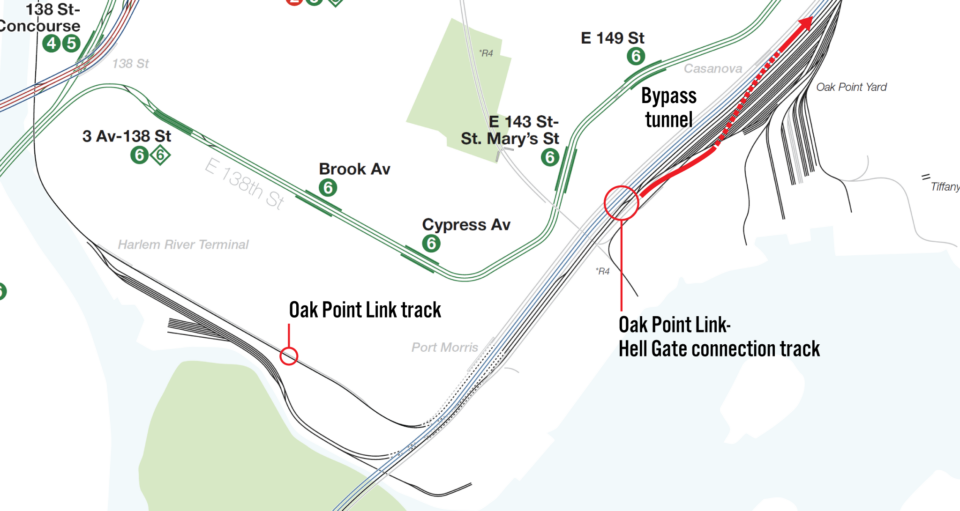

The viaduct splits down the middle as it enters the Bronx, allowing two additional trackways to enter between the central bridge tracks and pass under the bridge. This connects to the Oak Point Link track, a single track that shirts the Harlem River, used by CSX trains coming down the east side of the Hudson River. This is the only point south of the Selkirk Yard where trains can access New England. Therefore, the Oak Point Yard tracks cannot be obstructed.

Presently, the two passenger tracks on the west side of the bridge do not conflict with the freight track on the east side. But if all four tracks are to be used for passenger service, the eastern pair of tracks would need to bypass the track connection into the Oark Point Yard. A 2-track tunnel will need to be constructed under the southern edge of the Oak Point Yard, which would come above ground between the 149th St and Leggett Ave bridges. The center two tracks would still connect to the yard, and passenger trains would avoid the junction.

ROUTE

The RPA had proposed two different alignments for their Triboro Line through the Bronx. The first would continue trains up along the NEC to Co-Op City. The second reused the abandoned Port Morris Railroad tunnel, which ran from the banks of the East River in Port Morris to 149th St and 3rd Ave through St. Mary’s Park.

Each alignment has their pros and cons. The Co-Op City/NEC alignment seems the simplest, as IBX trains could run on existing tracks. However, the PSA project is building the new Metro North stations on the inside pair of tracks along the NEC. With the IBX tracks running on the outside of the bridge, this would require another flyover to allow IBX trains to access the Metro North stations. Building a new set of tracks for the IBX is also possible, but would be the most costly option.

Further, sending the IBX to Co-Op City would change the nature of the line. The IBX is a circumferential line, meaning it runs around the center of the city and connects different radial lines which run between the city center and suburbs. By shifting the IBX into a radial line, it focuses ridership that is bound for the core of the city to transfer unnecessarily, and would cause congestion on Manhattan-bound trains. This is exaclty why the G train was removed from the Queens Blvd Line, in favor of more Manhattan-bound service.

There is a strong argument to be made that a cross-Bronx subway is needed. However, if the IBX is to run along the NEC, it doesn’t fill this role. In fact, it would provide only one transfer to an existing subway line, the 6 train at Hunts Point Ave. This further reduces its ridership potential.

The Port Morris Line, running along an abandoned rail tunnel, does continue the circumferential nature of the line, creating a cross-Bronx transit line which directly serves The Hub of the Bronx. But this seemingly more logical alignment has issues as well. The actual track connection between the bridge and tunnel never existed in the first place, requiring adjacent buildings to be demolished to make such a connection. A new station near the 6 train at Southern Blvd and 142nd St would require demolishing adjacent buildings, and constructing a long passage to the subway. The new tunnel section would need to navigate around the existing tunnels near 3rd Ave, likely requiring deep and expensive stations.

FREIGHT

Given how long it has taken to get the Gateway Tunnel between New Jersey and Penn Station under construction, not to mention the immense cost, it is hard to imagine that an even longer, more expensive tunnel that will see far less service, and is not necessarily a vital link in the nation’s rail network, will be built anytime soon. The PANJNY even quietly acknowledges this by proposing a first phase of the project that sets up a single operator for the combined rail and barge operation between Greenville Yard and Bay Ridge, and a new operation to Oak Point Yard in the Bronx.

While the IBX gained political support due to the inclusion of freight rail improvements, there is little to suggest that this means the Cross Harbor Rail Tunnel is actually going to be built anytime soon. Under an enhanced rail and barge scenario, the PANYNJ projects that the Hell Gate Bridge will still only see up to 5 freight trains a day. In their EIS for the Cross Harbor Rail Tunnel [Warning: 37mb PDF], the PANYNJ forecasts between 7 and 12 freight trains a day will use the bridge once the Cross Harbor Rail Tunnel is open.

A question that I have seen asked time and time again by passenger rail advocates is “why can’t freight just run at night?”. The truth is, it already does. While freight rail does run on dedicated tracks over the Hell Gate Bridge and Bay Ridge Branch, it still must work around the very busy LIRR passenger service. Most deliveries to businesses along the LIRR are done at night. This leaves little extra room for moving larger trains over the Hell Gate Bridge at night (which already happens, too). Even if Metro North/Amtrak service was segregated to a single track between 11pm and 6am (when service is the lightest), it would be hard to move every freight train in that window.

The issue isn’t actually the bridge; with a window of 5 or 6 hours, you can easily move 6 or 7 freight trains over the bridge. The problem is that once on the other side, you need to put those trains somewhere. Freight operations require trains to be disassembled and rebuilt at either the Oak Point Yard in the Bronx, or Fresh Pond Yard in Queens. While both PSA and IBX are planning on improving freight-used tracks along both corridors, service will always be limited to a single track.

There simply is not enough track space on either side of the bridge for each one of these trains to wait all day, cross the bridge at night, and be unloaded. To say nothing of the man power (i.e. labor costs) involved with this type of operation each night. CSX would have to redesign its entire freight service through the northeast to manage this. More likely, they would simply choose to not use the bridge at all, continuing with their round-about service through Selkirk, adding more trucks to regional highways.

Would it be possible to run more, but shorter trains, that would fit within the frequency of Metro North and Amtrak service throughout the day? Yes, however, it would greatly reduce efficiency and greatly increase costs. What makes freight rail so efficient is that a lot of tonnage can be moved at once, making them incredibly cost effective. Running shorter trains would take far more man-hours to build and run. In fact, the main benefit of the Cross Harbor Rail Tunnel is that with a single operator, more freight tonnage can pass through the region quicker, and more affordably for customers.

Unlike passenger rail, freight trains often operate when they are ready to go; freight doesn’t have to be in the office at 9am. Passenger rail trains strive to hit an on-time window of a few minutes. Freight rail strives to hit this same window in hours. This is what makes mixing freight and passenger rail such a bad idea.

NO ERRORS, NO GROWTH

Passenger and freight rail operators are looking at how to accommodate future growth. Trying to fit all these services across a finite crossing creates a scenario where there is no room for error, and certainly no room for growth. Anytime there is a train delayed on the NEC, it will ripple down the line, and potentially affect the IBX and CSX. I’ve talked before about the problems with interlining on the New York City subway. There, each service runs on roughly the same frequencies, and there are switches that allow trains to use other tracks as bypasses. There are no such luxuries on the Hell Gate Bridge. Worse, the investment needed to bring the Hell Gate Bridge up to capacity for the IBX, not to mention the additional tunneling needed in the Bronx, means that billions will be spent for a project that we can today see will be problem ridden and obsolete the day it opens.

While there is a scenario that gets the IBX to the Bronx, it does so by limiting Metro North, Amtrak and freight traffic. Since Amtrak owns the Hell Gate Bridge, why would they ever agree to such an agreement? Even if the projected freight traffic doesn’t appear, we know that passenger traffic will. With investments like the Gateway Tunnel and new bridges on the NEC in Connecticut, Amtrak is looking towards the future, where there is more regional and high-speed rail on the NEC. Metro North service will likely be popular as well. If the IBX is shoehorned over the Hell Gate Bridge, these investments will be artificially capped in their potential for improving regional travel.

The Hell Gate Bridge was designed by famed bridge builder Gustav Lindenthal. Lindethal overengineered the bridge so that it could support more weight in the future. There are two wide trackways on either side of the main span. These trackways, along with the small decorative arches in the towers on either side (above, in orange), are wide enough for trains to pass through should any serious proposals for streetcar service have been proposed. In 1920, when the parallel Triborough Bridge was first proposed, Lindenthal proposed an alternative that would add a second deck on the Hell Gate Bridge for cars. But even Lindenthal admitted that while the main span could support additional levels (or tracks on the side), the approach viaducts could not, and that new approaches would be needed.

Should the IBX over the Hell Gate Bridge be popular, there will come a day when more capacity over the bridge is required. But while the main span can support up to six tracks, the viaducts on either side cannot. The most realistic scenario is not to rebuild the viaduct, but built single track viaducts on either side of the existing span. This will require extensive property takings. On the Astoria side, up to 128 properties would need to be removed on either side of the viaduct for new tracks to be built.

Running all services (IBX, Metro North, Amtrak, CSX) over the Hell Gate Bridge only works if you can reduce service on each, and manage when trains use the bridge. If Metro North/Amtrak service during the midday is reduced from every 15-20 min to every 20-30 min, you can squeeze in room for an additional freight train. Assuming that the Cross Harbor Tunnel is not built anytime soon, this might be enough of a balance to make it all work. But when trains get overcrowded and riders demand more service, there will be nowhere to go.

The costs and complexities of such a scheme are not to be taken lightly. While the entire IBX is projected to cost $5.5 billion, which will more likely reach close to $7 billion with the design changes and added tunnel. It’s safe to assume that a Bronx extension could cost close to the same, due mostly to the needed tunneling and underground stations. If service will always be limited, this seems like a foolish investment.

Stopgap: Metro North-IBX Station?

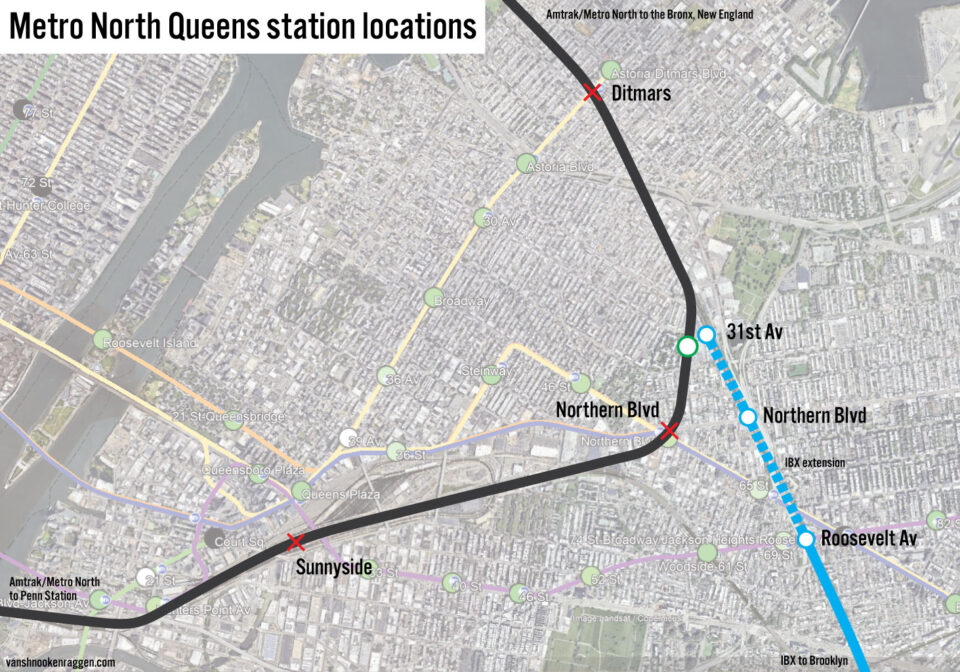

If the MTA is building PSA and the IBX through northeastern Queens, could a simple stop-gap solution be a station for both? When PSA was first being discussed, some transit activists called on the MTA to add a station in Queens. Building a stop on the line would, at the very least, provide a real connection between boroughs. The MTA considered two locations:

The first was the aforementioned station at the Ditmars Blvd terminal on the N/W trains. The cost of building a station here would be very high, including eminent domain and rehabilitation of the +100-year-old concrete arch. Due to the double fare between subway and Metro North, the MTA saw few riders making the trip. Most riders from the Bronx, Westchester, or Connecticut have little reason to get off in Astoria, which is a heavily residential neighborhood. Likewise, few residents in Astoria would be making a reverse commute who would also be willing to give up their cars.

A second location was considered in Sunnyside Yards. While the MTA was building East Side Access (ESA), they left room at the southern end of the complex Harold Interlocking, at Queens Blvd, for a station on the LIRR Main Line. A component of ESA was building bypass tracks under Harold Interlocking for Amtrak trains to cross over the LIRR Main Line without blocking service. As Amtrak uses the middle platforms at Penn Station, it needs to access them via the southern pair of tracks of the four East River Tubes. The southernmost track has a bypass track, but the northern one doesn’t.

Neither the station nor bypass tracks were built, but the tunnels for them were constructed. The portal for the westbound tunnel was built parallel to the proposed station. The track grade in this portal is too steep for an ADA compliant platform. The complex design of Harold Interlocking means there is virtually no way that Amtrak/Metro North trains could stop anywhere near the proposed Sunnyside Station.

A third location (which I’ve proposed in the past) is where the NEC crosses Northern Blvd and Broadway. Unfortunately, the large curve in the track is too wide for ADA compliant platforms. The track could be straightened out, but this would require taking a number of homes and businesses next to the tracks. The station would face the same double fare issues as the Astoria-Ditmars stop as well.

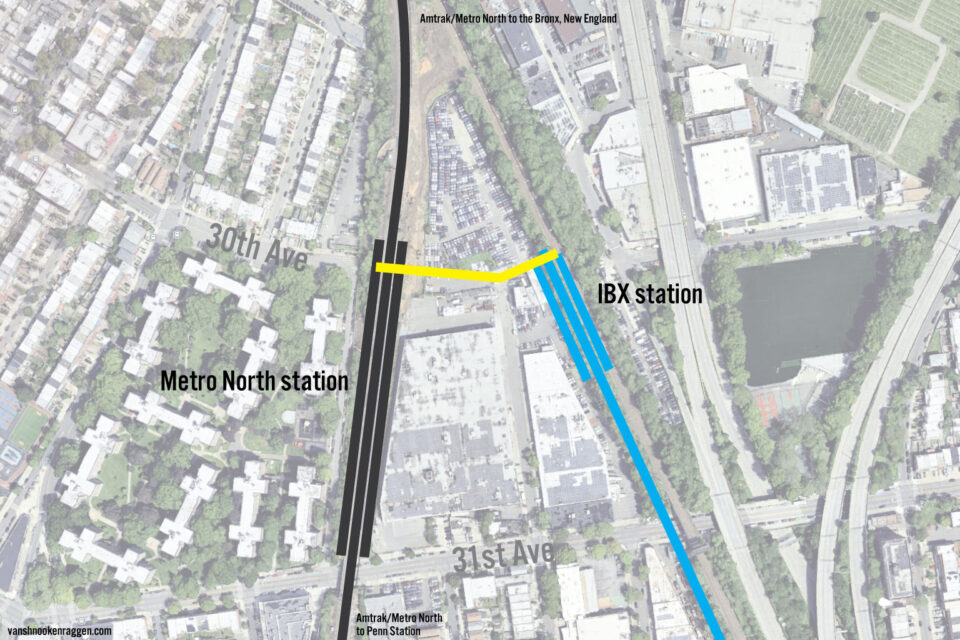

Along the NEC through Astoria, before the NEC meets the Fremont Secondary tracks at Bowery Bay Junction, there is a straight section of track that crosses over 31st Ave between 56th St and 57th St. If the IBX were to be extended north to 30th Ave, the station would be almost 400 feet away from the Metro North station.

On paper, this works for such a station. However, this side of Astoria doesn’t have much in the way of development (it sits at the southern edge of St. Michael’s Cemetery), or other transit connections to draw ridership. The headways of each service would mean that riders from the IBX would face longer wait times when transferring to Metro North, on top of a double fare. Metro North trains stopping here would also delay Amtrak trains behind them. This is why PSA is being designed with separate tracks between Amtrak and Metro North. With few existing transit connections between the Bronx and Queens, this will make building ridership a costly uphill battle. Anything short of a direct line connecting the two won’t be enough to build long term ridership. Alone, neither of these stations would support themselves.

Conclusion

All things considered, it’s no wonder why the MTA eliminated the Hell Gate Bridge from the IBX plans from the very beginning. Ultimately, with possession being 9/10ths of the law, anything related to the bridge is at the discretion of Amtrak. If they see the IBX as an impediment to their service, it’s a non-starter, no matter if it’s technically feasible in a narrow window.

It’s also worth pointing out that it will take time for the IBX to be financed and built, meaning that there is a point in the not too distant future where we will have a better idea of traffic and demand, and potentially Amtrak will feel differently. After all, it was Metro North which held up construction of the new Tappan Zee Bridge because they insisted on space for a new train line, until Gov Andrew Cuomo killed the idea and pushed the bridge to completion.

In a strange twist of fate, transit activists should be careful what they’ve wished for here. It wasn’t so long ago that the Hell Gate Bridge was being looked at more for it’s value as scrap rather than transit. Today, the bridge is seeing many suitors. In the near future, we will see more Amtrak inter-city service, a new Metro North service to Penn Station, and more freight that is being removed from congested crossings. The Hell Gate Bridge can be many things, but it can’t be everything.

Special thanks to Jared Maldonado for helping with this post.

Cross Harbor Freight Tunnel is going nowhere: https://bqrail.substack.com/p/no-activity-on-the-cross-harbor-rail

PANYNJ is leaning towards increased float traffic, not building a boondoggle tunnel at this point. Hell, one of the main reasons the PANYNJ was created was to build that tunnel, they’ve got over 100 years of history that says it will likely never be built …

https://junipercivic.com/juniper-berry/article/letters-to-the-editor-update-on-cross-harbor-and-ibx its actually not dead ! That same person wrote this three months later and i have spoken to a Port Authority rep as well that said the Cross Harbor Frieght Program is advancing.

Thanks for this look at why it is not practical for the IBX to reach the Bronx at this time, especially given that the Hell Gate Bridge is controlled by Amtrak. If there was a way to do it, though, it would certainly be advantageous for travel between The Bronx and Queens. And this would be true regardless of whether it simply went to Co-Op City. If the IBX is reasonably successful, then perhaps some time in the future, an additional connection to The Bronx bypassing the Hell Gate Bridge might be financially feasible. One result of the IBX may be further crowding at Roosevelt Avenue, 74th St., Broadway. That station complex has been about number 10 in ridership in the entire system. The other thing I wonder about is whether the presence of the IBX will have a negative effect on trying to get the QueensLink accomplished. It would only run a little to the East of the IBX and not be as useful. In a world of limited resources, I could see it losing out, which would be a shame.

With regard to Bronx-Queens service, what about leveraging the new stations that are being built for PSA, and running a heavy-rail passenger service from them that connects to the Bay Ridge branch? That could use the existing (single track) CSX trackage over the Hell Gate – it might not be as frequent, but it could still provide a useful connection, both to the subway (the tracks go under Roosevelt Ave just east of the existing #7 Broadway station) and to the LIRR (a joint station between Queens Blvd and 51st Ave could serve both the Port Washington line and the LIRR Main Line as well as the Bronx-Queens service).

Frequent, reliable service is attractive to riders. Infrequent service, which also costs more to run because of LIRR/Metro North labor contracts, will absolutely not attract enough ridership to justify its existence.

As a Bronx native, I’ve got to agree. Even if the IBX (a name I really don’t like because it sounds like a bad intestinal disorder) were closer to the original Triboro Rx proposal, I feel that it would be of limited benefit to Bronx transit riders heading to Queens if it remained entirely on the Northeast Corridor. To benefit a greater amount of transit riders it would need to break off from the Corridor and travel crosstown across The Bronx and connect with most of the borough’s subway lines and the existing Metro-North lines. But that would require tons of money for significant new construction. I think Penn Station Metro-North is a better option for areas of the eastern Bronx that the Corridor passes through. I wonder if it would be possible to add a station somewhere in Long Island City which can connect to several Queens transit services that converge there. Possibly also LIRR. That would be a direct Bronx-Queens connection right there.

The TriboroRX extension to the Bronx is feasible. If anything the TriboroRX should be extended to Hunts Point. I don’t see Metro North ridership into Manhattan having a high demand.

Thanks for the detailed explanation. Many assume that just because a track exists, there’s room for another service. But mixing speeds, frequencies, and the lack of a takt schedule, makes some concepts impossible. For the same reason, it seems that Amtrak to Ronkonkoma is a bad idea. So is Cross-LI Sound HSR, (even if America could build such a tunnel project anymore), via Mainline or an electrified PortJeff. Would need new ROW and many many takings. (Been reading a lot of pedestrian observations dot com).

Grew up in Co-op City in the 70’s when it first opened. Boy, how we would have loved a one stop extension from Pelham Bay -6-. Pres Ford told NYC to drop dead, and that was it. Fifty thousand people live in Co-op City; Bay Plaza attracts a lot of E.Bronx car traffic that would otherwise have gone to Cross County (Yonkers) or other similar.

The new Penn Access station will be in the extreme southern corner of the neighborhood, an easy walk for only 1/3 of the people, the opposite end is a 30 min walk, or a 15 min bus ride. Station is squeezed between the Hutch R. and a mess of highway ramps, no one from Pelham Bay will come. For a $7 rush hour City Ticket, it will get some use, as Co-op is I think the most heavily used of the E.Bx. express buses. Having Einstein Hosp. two minutes away will be great; Ability to reverse commute to New Rochelle and Stamford without a car will help.

Question

How will Penn Access be able to keep to schedule, given that —

— construction of replacement bridge over the Hutch not starting until 2029;

— construction of a flyover at Shell Interlocking (New Rochelle) has no date nor funding.??

Thanks so much for the great response. You’re right that Co-op City deserves more. Yet, you don’t even here leaders in the Bronx calling for it.

Can’t answer your questions about PSA, I’ve not been following it that closely.

Excellent explanation (as usual). I have only one quibble. There is no significant difference in costs of high level vs. low level platforms. The reason why the cost estimates for IBX stations in the CR mode was greater than in the LR mode was primarily because platforms were twice as long for CR and were heated for snow and ice removal, which the LR platforms were not. Also, these costs were a tiny part of the total project cost.

Thank you. BTW, your page, and your work, is great.

Question: What is the basis for suggesting that a “bench wall” (side walkway) is not necessary in a tunnel when power is provided by an overhead catenary, rather than a third rail? My understanding is that it is required in any case by the fire safety rules, so passengers can exit by side doors. (See https://bqrail.substack.com/p/full-size-trains-for-the-interborough).

It’s purely safety. It’s a massive liability to have people walking along the tracks when there is an active third rail next to them. It’s one thing for a track worker (which is also why it’s such a dangerous job), but for the riding public it’s non-negotiable. With an overhead wire, you don’t have to worry about this.

As for the fire code, a bench wall is needed for high-level rail cars because how else would passengers get down? But with low-level LRVs, they are already close enough to the ground.