When Duke Ellington wrote “Take the A Train” he wasn’t talking about Brooklyn. Today, the A train runs from Washington Heights at the upper tip of Manhattan, to southern Queens and the Rockaway peninsula. It is, in fact, the longest subway line in the city (especially when it runs local late at night.) But while the A in Manhattan is a venerable workhorse, once it reaches Brooklyn, things change.

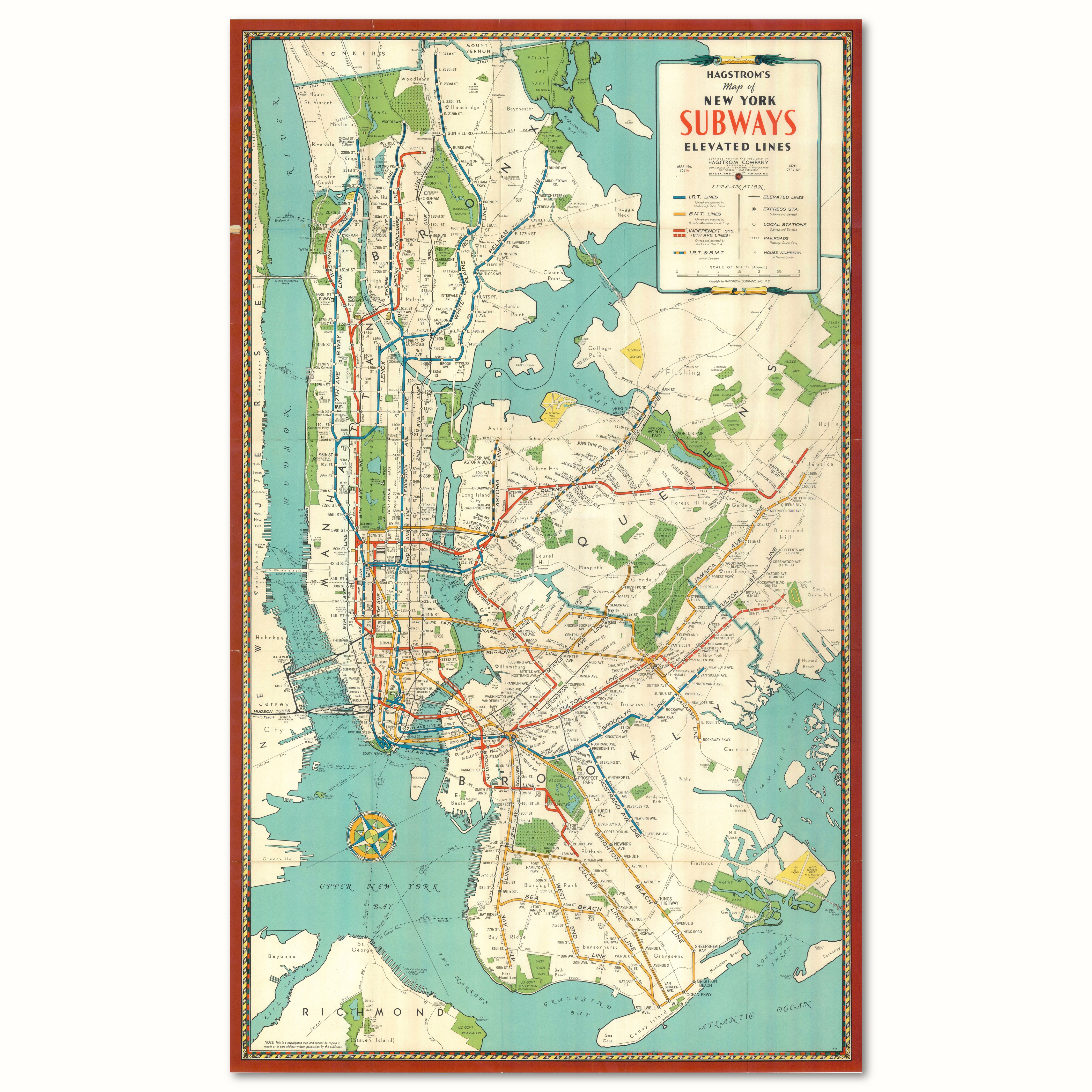

The A train formed the backbone of the entire Independent City-Owned Subway System, better known as the IND. From the beginning, the IND 8th Ave Line, along which the A runs, was designed as a massive passenger sorter, taking in riders from Washington Heights, Harlem, the Bronx, Queens, and Brooklyn, and sifting them all throughout Manhattan.

These branches are not all the same. The lines which truncate along Central Park West, and those which come in from Queens, are usually packed with straphangers, usually pushing subway capacity to its limits. But in Brooklyn, tunnels see far fewer riders and can handle fewer trains. Riders might complain about packed trains on Queens Blvd, but at least those come ever 2-3 minutes. On Fulton St, if you catch a C train in 8 minutes, you’re lucky.

Why is there such an imbalance? It’s the typical tale of money, power and changing times. The sorry state of the A train in Brooklyn wasn’t supposed to be this way. The city had high hopes for the line, and for what it could do for the borough. But in the end, the IND Fulton Line was to be the last subway that the city built in the borough of Brooklyn, left unfinished, with dreams of better service long forgotten.

Early Days

Like so many things in Brooklyn, it all began with the bridge. Before the Brooklyn Bridge opened in 1883, the city was more of a dense suburb that still had working farms on its outskirts. With a direct connection to New York, Brooklyn came into its own. Trolleys over the bridge opened up vast estates for redevelopment. This development boom created what we today consider the most quintessential neighborhoods in Brooklyn: Park Slope, Prospect Heights, Fort Greene, and Clinton Hill (even though that’s a much more modern name for the area). A sleepy crossroads known as Bedford soon began to urbanize.

Rail transportation in Brooklyn was not new. The Long Island Rail Road began in 1834 from Brooklyn as a means of reaching Boston via Greenport. By the 1880s, Coney Island had become a summer destination for well-to-do families from New York and Brooklyn. Many of them reached Coney Island by means of a ferry to short railroads. None of these lines were really set up for commuting as we think of it today, nor was suburban development all that prevalent before the Brooklyn Bridge opened.

Elevated mass transit as we think of it today saw its development in New York after the Civil War. In Brooklyn, the first elevated line opened in 1885 from the Fulton Ferry to Broadway, via Washington St and Gates Ave. Many of the steam railroads ran north-south to serve Coney Island, but the east-west lines were still horse-drawn trolleys. The new El train whisked riders above the streets and congestion.

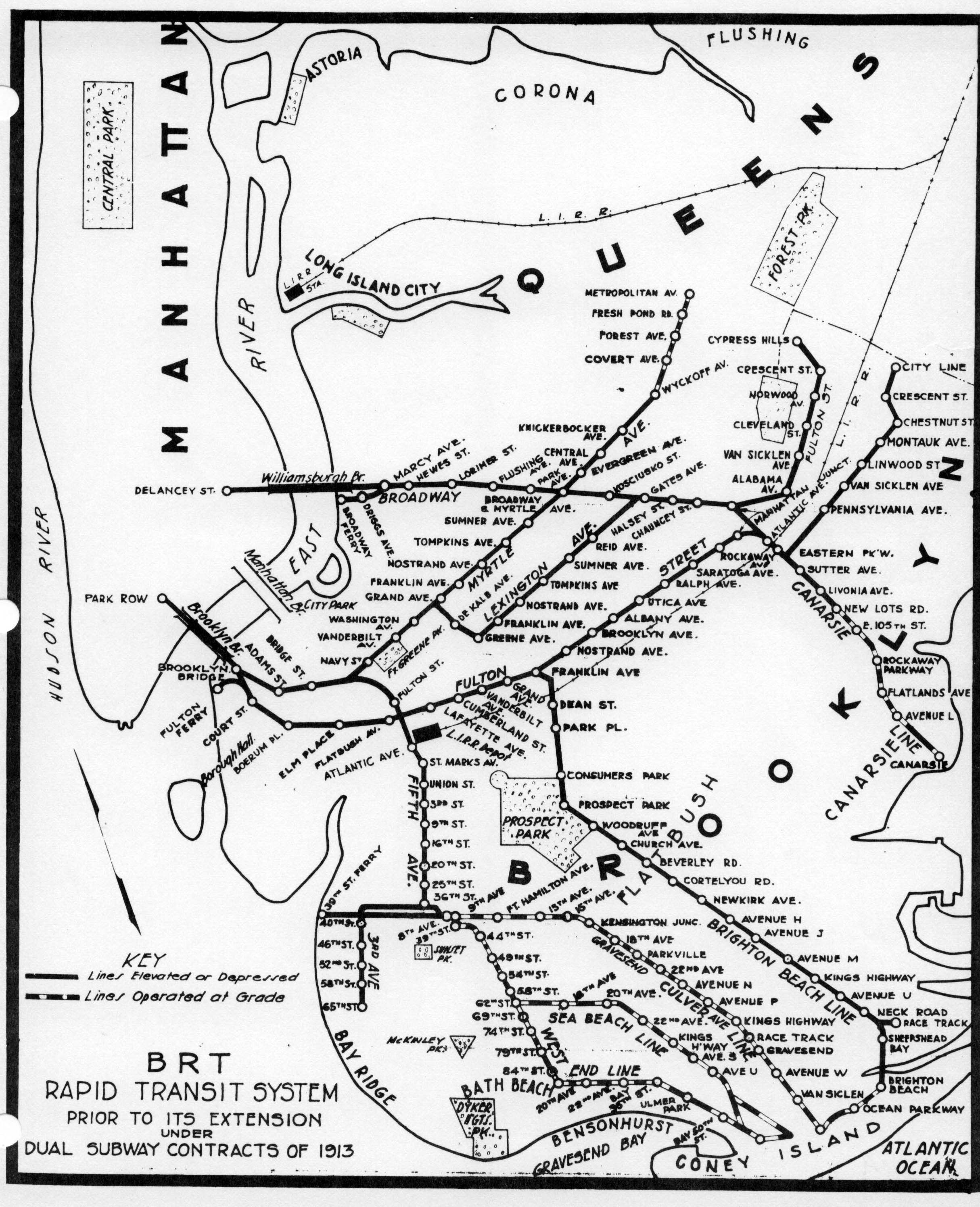

The predecessor of the IND Fulton St Subway was the Kings Country Elevated Railroad which opened in 1888. Originally, the line ran from the Fulton Ferry Landing, down Fulton St, to Albany Ave. From there it was extended east to Ralph Ave. The line was reincorporated as the Fulton Elevated Railroad in that same year to allow it to expand from Ralph Ave to the city line (it also had the right to build a north-south elevated line into Greenpoint, which was perhaps the first inkling of what became the IND Crosstown Line.)

The line was extended to Manhattan Junction (today, Broadway Junction), then down Van Sinderen Ave to Pitkin Ave in 1889, then along Pitkin Ave to Grant Ave in 1894. The company leased the Brooklyn and Brighton Beach Railroad in 1896. This steam railroad ran from the corner of Bedford and Atlantic Aves, through Crown Heights, all the way to Brighton Beach. The connection to the Fulton St El converted the line to electric power and allowed rapid transit trains from New York to directly run to Brighton Beach.

The Subways

In 1898, the City of Brooklyn ceased to exist. By popular vote (just barely in Brooklyn) the City of New York had annexed Brooklyn and a number of small towns in Queens and Richmond Counties (the Bronx had been annexed in two parts, the first in 1874 and the second in 1895). Part of the reasoning behind this consolidation was the New York had the resources (money and water) to grow, while Brooklyn, Queens, the Bronx, and Richmond (before it was officially changed to Staten Island) had the land for growth, but not the resources.

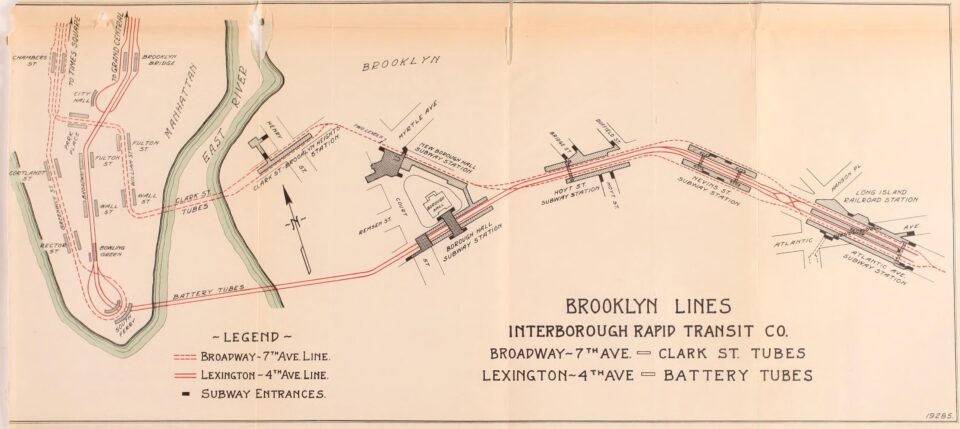

The first subway opened in New York in 1904, and 4 years later had been extended through Brooklyn Heights to Atlantic and Flatbush Aves. The original contract for service was awarded to the Interborough Rapid Transit Co. (IRT) which controlled the streetcar and elevated lines within Manhattan and the Bronx. The many private lines operating across Brooklyn had been consolidated, one after another, into the Brooklyn Rapid Transit Co. (BRT). This company didn’t look too kindly to this interloper from New York entering their territory, and soon began to fight for the rights to build and operate new lines from Brooklyn to Manhattan.

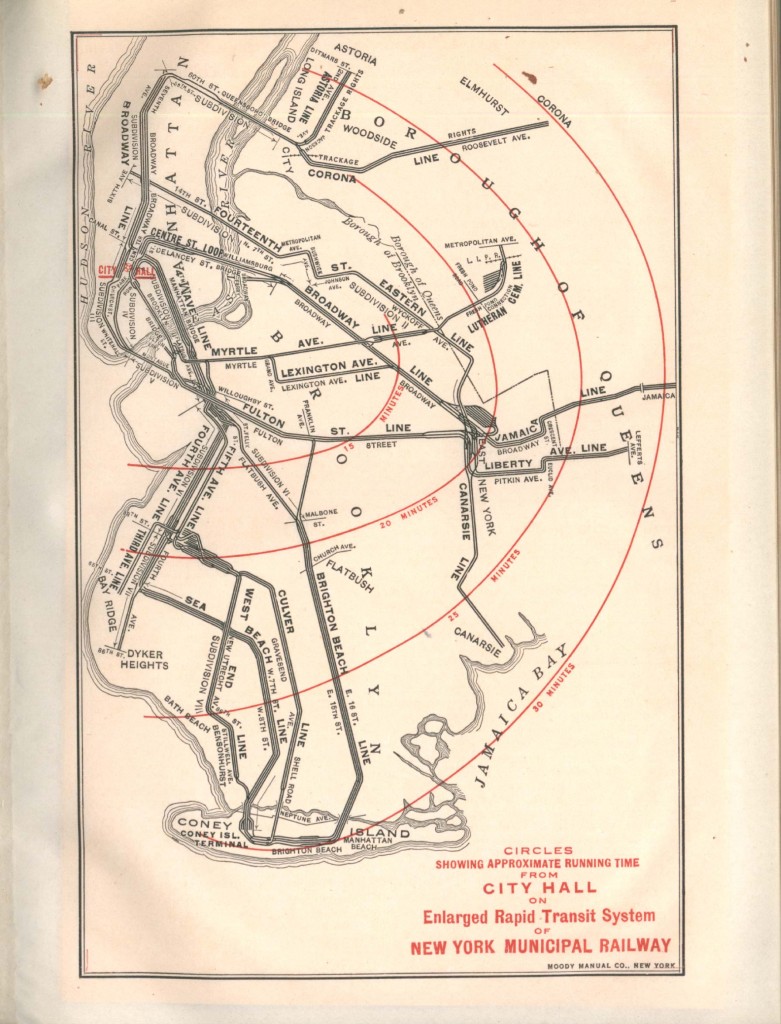

The BRT operated a massive network of streetcars and elevated lines which all funneled riders to the two bridges between the boroughs, the Brooklyn and Williamsburg Bridges. The Manhattan Bridge was built with space for two subways and trolleys, but the dispute between the city, IRT and BRT meant that no one knew who would run them. At the time, many, but not all, lines crossed each bridge and deposited their riders at large terminals on the Manhattan side. The BRT wanted to build subway tunnels to connect these lines deeper into New York. Doing this would also create demand at the other ends of the lines, sparsely settled areas in southern and eastern Brooklyn. That potential ridership meant money.

The Dual Contracts, a story in its own right, were signed in 1911 between the City of New York, the IRT and the BRT. These contracts divvied up the new subway lines, and allowed the BRT to rebuild many of their older lines for the new service. The old steam lines to Coney Island had been converted to electric power in the 1890s. Many of these still ran on rails at grade, down the center of city streets. These were rebuilt on large new elevated structures, much stronger than the elevated lines from the 1880s. The Fulton St El was reinforced, and a third track was added to allow for partial express service.

Their plan was simple: connect all the elevated lines with new subways that loop trains through Manhattan and back into Brooklyn. The heart of the BRTs new subway system was DeKalb Ave station. Through this station would funnel trains from southern Brooklyn, looping through Lower Manhattan or heading uptown and into Queens. Trains from eastern Brooklyn would mainly use the Brooklyn and Williamsburg Bridges, looping trains via the new Centre St Subway.

On paper, this plan worked. In practice, the subways created so much new demand for service that DeKalb Ave station became an intense bottleneck that limited service on each branch. The original plan to have Williamsburg trains loop back over the Brooklyn Bridge was scrapped when the connection to the Brooklyn Bridge from the Chambers St subway station was built, but the BRT refused to pay an extra fee to the city to use it. A new tunnel connection under Broad St was held up due to engineering challenges, and wouldn’t open until 1931. The loss of these two connections meant that far more trains had to run through DeKalb Ave than was originally planned.

The BRT originally wanted to connect the Fulton St El and Brighton Beach Lines to DeKalb Ave via a ramp at Ashland Place. However, planners foresaw that such a connection would make DeKalb Ave even more congested and that a new subway would eventually be needed. A provision was built into the subway tunnel at the corner of Fulton St and St. Felix St, where the Brighton Beach Line connects to the DeKalb complex, for a future Ashland Pl connection.

Brighton Beach trains were rerouted along Flatbush Ave for a direct connection to Manhattan. The former elevated connection at Fulton St and Franklin Ave was cut back to a shuttle train, with some direct service to Coney Island in the summer. The MTA still runs this service today as the Franklin Ave Shuttle.

What to do about Fulton?

With subway service opening up new areas for suburban development, the 1920s saw a vast outflow of residents from the Lower East Side and older areas of downtown Brooklyn into the fields of Gravesend and Flatbush. Property owners in the older brownstone neighborhoods began to cut up homes into apartments and flop houses. This lowered property values and dismayed landowners. They saw the old El trains as an impediment to development and wanted them gone; keeping property values higher would retain wealthier residents.

Before the opening of the subways, the elevated lines to downtown Brooklyn all converged at a giant, multi-level complex at the base of the Brooklyn Bridge, the Sands St Station. This structure dominated the heart of downtown Brooklyn. The station was really three stations: a terminal for former trains to Fulton Ferry (which was itself served by shuttle trains), a through station for trains over the bridge, and a loop for trains which couldn’t fit. When the subway opened, the Sands St complex saw a drop in ridership as passengers chose to take the subway into Manhattan instead. Business owners and landlords began to petition the city to remove the structure.

The BRT 4th Ave Subway had meant that the old 5th Ave El was redundant and antiquated. But subways to the east had not yet been built (a subway along Lafayette Ave was proposed by both the IRT and BRT), but the BRT was not interested in building expensive tunnels when there were a number of money making elevated lines already running.

At Broadway Junction, the Fulton St El met up with the Broadway El trunk line (which itself had branches along Myrtle Ave, Lexington Ave, and Jamaica Ave), the Canarsie Line, and the Liberty Ave El. Here, riders could transfer, or have direct one-seat-rides, to a number of destinations in Brooklyn, Manhattan, and Queens. These complex service patterns made the prospect of expanding subways out this way more complicated, but it also meant that any number of these lines could act as feeders into the new tunnel, providing more service and higher ridership.

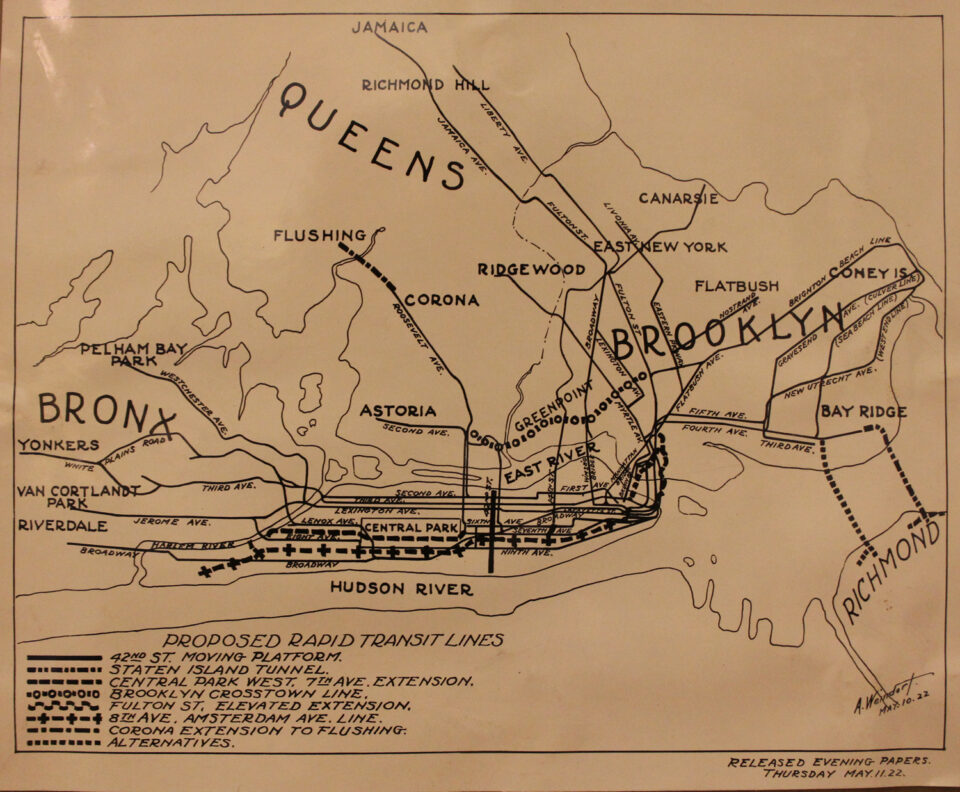

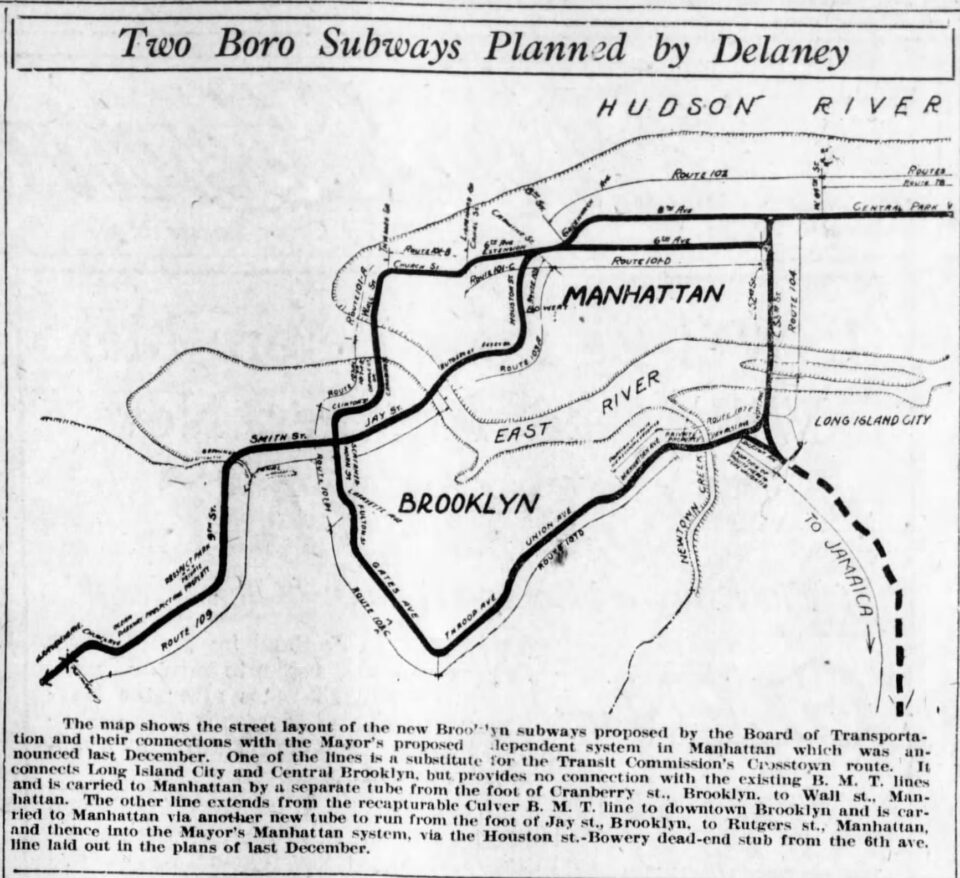

After the lines of the Dual Contracts were completed, the city began preparations for a new round of tunnels. The city was interested in a new Manhattan trunk line for the west side, a crosstown line between Queens and Brooklyn (which the BRT had the right to build, but faced backlash against a new elevated line since they refused to build a subway), and a new tunnel under the East River for the Fulton St El to use. While the original 8th Ave Line was proposed to consist of 8 tracks, it did not include a connection to the proposed Fulton St tunnel.

The tunnel would begin at Clermont Ave at Fulton St in what is today Clinton Hill. The elevated train would drop into a tunnel which would run along Fulton St, then turn north under Fort Greene Pl, turn west along DeKalb Ave, where a transfer station would be built. After Flatbush Ave Ext, the tunnel would cut across private property to Livingston St, running west to Clinton St.

Google Map showing existing subway tunnels between Lower Manhattan and Brooklyn, 1922, and the proposed Fulton St Connection (heavy black and gray lines). The eventual IND Fulton St tunnel, under Cranberry St, is shown for context, though it did not exist in 1922. Source: NY Times 05/12/1922

After this point there were two alternatives: the first would cut a direct path under the East River to Broad St, running north under Broad St to Nassau St, and then passing under Park Row to link up with the lower level of the BMT City Hall station (the lower level was built but has never been used for revenue service.) The second alternative would turn the tunnel north, under Clinton St to Old Fulton St, then cross under the river to Beekman St, to Ann St, finally curving north under Broadway to connect with the lower level of the City Hall station.

Then came John Hylan.

A Third Party

John Hylan was a lawyer who was first elected mayor of New York in 1918. So the story goes, Hylan was fired from his motorman job at the BRT when he missed a stop and caused a crash. Supposedly, he was so incensed that, once mayor, he vowed to get back at the private “traction interests”, as the IRT and BRT were known at the time. Though most of the Dual Contracts had been built by the time Hylan was in office, he was able to thwart the private subway operators from expanding and raising the fare.

When it came time to develop new subway lines, Hylan was intent on having the city build them instead. He was not alone, as many reformers accused the private companies of running dirty, crowded trains to keep costs down and revenues high. There were calls for having the city unify the subways under municipal control. But, since the IRT and BRT had the rights for 50 years, there wasn’t much the reformers could do.

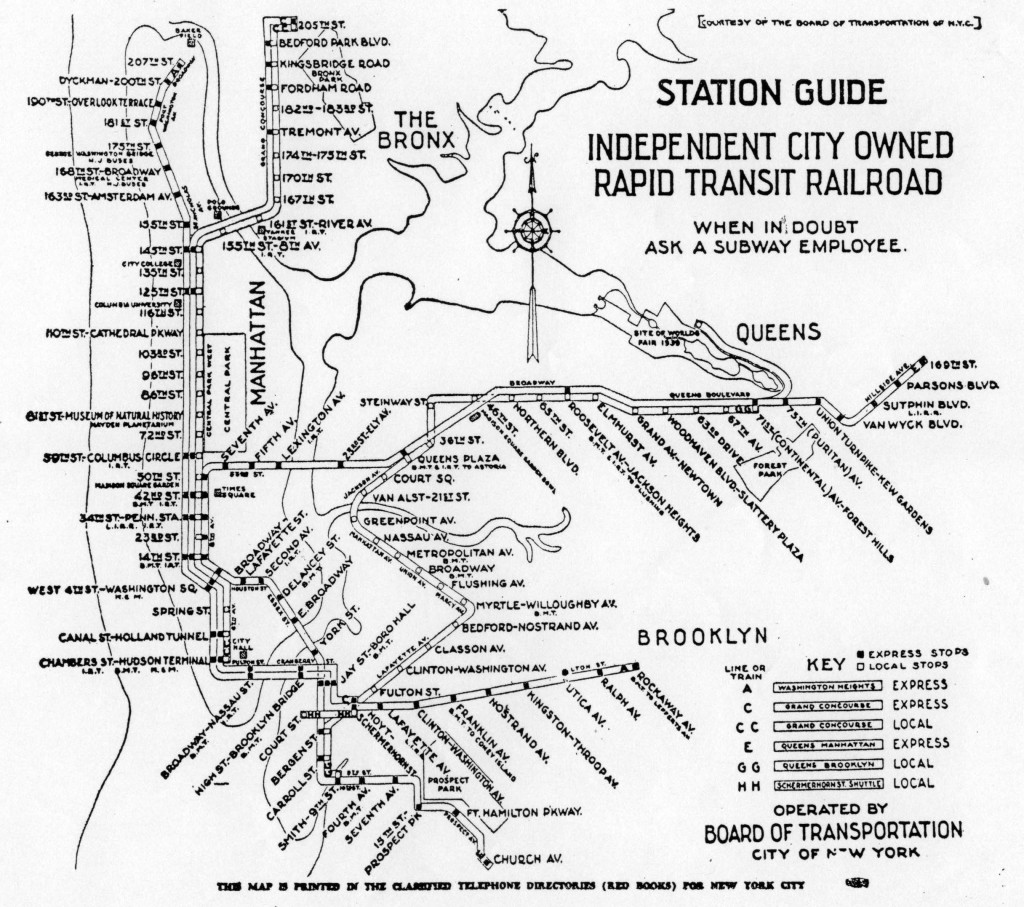

Hylan founded the Independent City-Owned Subway System (IND) with the aim to build the new lines and pick up any elevated lines from the Brooklyn-Manhattan Transit Co., the new company which had taken over from the old BRT in 1923. Planning for the new system began in 1924 and was focused largely around the two major trunk lines: the 8th Ave and Brooklyn-Queens Crosstown. Hylan stepped down from office in 1925, but the IND continued on.

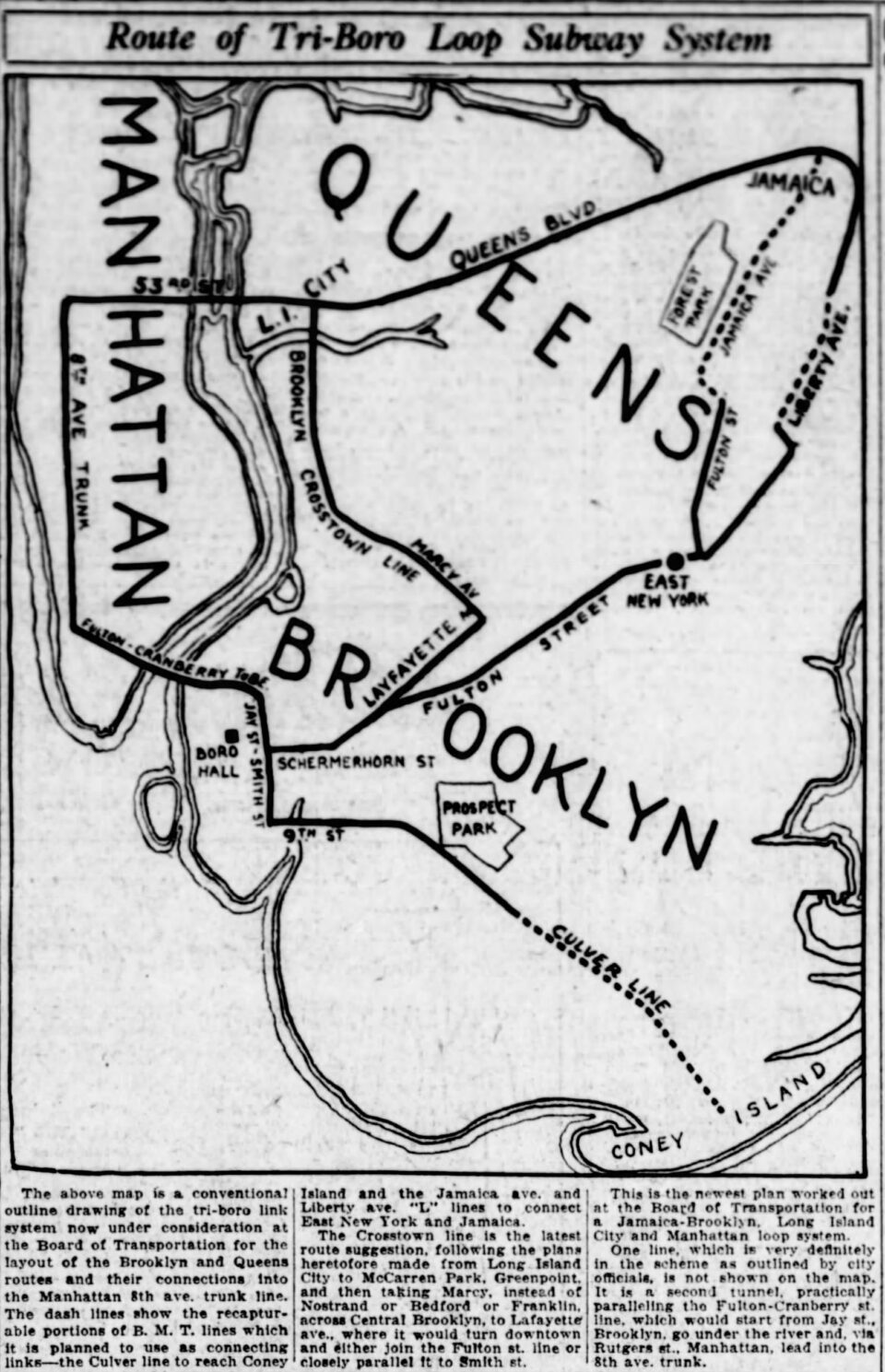

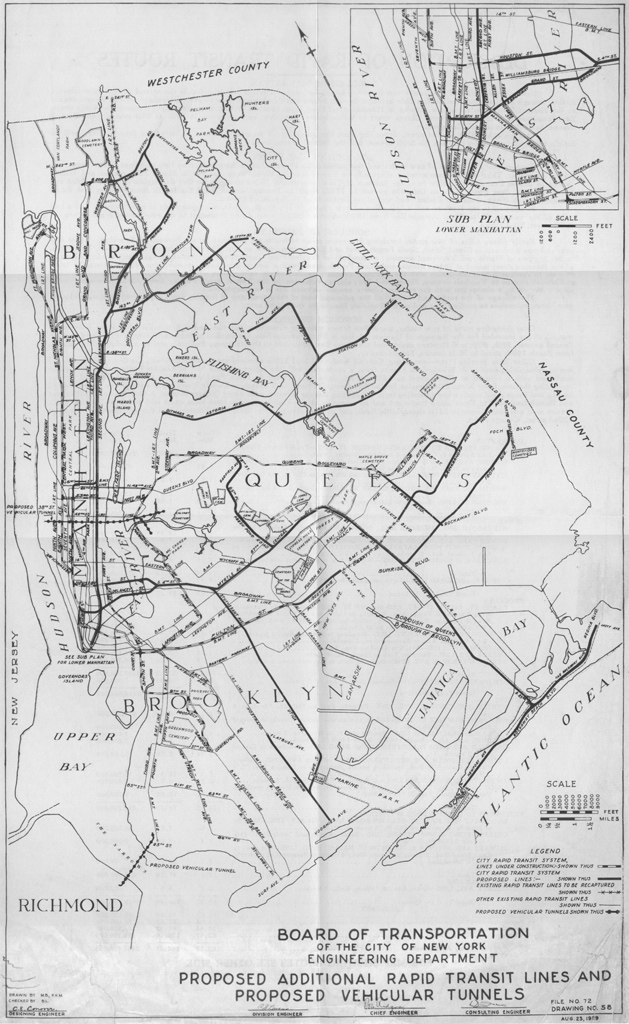

The city formed the Board of Transportation to plan and build the new system. The 8th Ave Line would form the backbone of the system, with the Crosstown Line forming a large loop between 8th Ave, Brooklyn, and Long Island City, Queens. The initial plans called for the Crosstown Line to have a wider arc than it does today: running under State St or Atlantic Ave to Hanson Place, then down Gates Ave to Throop Ave, up Throop to Union Ave and on to Manhattan Ave. Once in Queens it would loop back to Manhattan via 53rd St.

The 1922 proposal for an 8th Ave subway called for connecting the IRT Flushing Line to the trunk to run those trains downtown. The IND copied this plan by proposing a Queens line of their own. BMT trains coming from Coney Island were still bottlenecked by DeKalb Ave, so the IND proposed recapturing the BMT Culver Line via a new subway though South Brooklyn and Park Slope (IND Smith-9th Line as it was originally called.) To make sure the Bronx would support the plan, a branch of 8th Ave was proposed to run along the Grand Concourse.

In order for all of these trains to work efficiently, a second subway under 6th Ave was proposed. What had once been a simple new subway line was now an entire network. And the IND hadn’t even broken ground yet.

Brooklyn community and business groups pushed back on the IND plans. To them, what Brooklyn needed had been finalized decades before: when planning the Dual Contracts, the city proposed a 2-track subway from Flatbush Ave along Lafayette Ave to replace the Myrtle and Lexington Ave Els, and direct service to Manhattan for Fulton St trains. The IND plans were trying to split the difference between Lafayette Ave and Fulton St. Both required subways, and both were needed so that the hated elevated train tracks could be removed.

The IND shifted their plans to include a 2-track subway under Lafayette Ave and a 4-track trunk line along Fulton St. With the focus on Fulton St, the Crosstown Line connection to Manhattan was cut. With the addition of the Queens, Bronx, and Brooklyn branches, there now wouldn’t be enough service on any one line to cover both local and express. The IND decided to kill two birds with one stone and extend the Crosstown Line along the local tracks of the Queens Blvd Line and the local tracks of the Smith-9th St Line. Express trains would pick up though riders going to Manhattan.

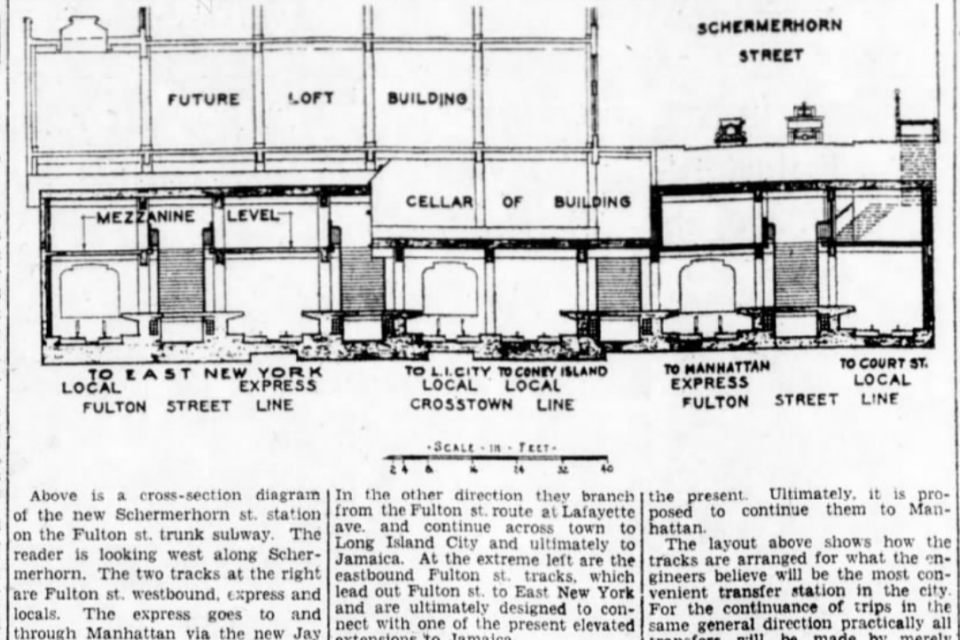

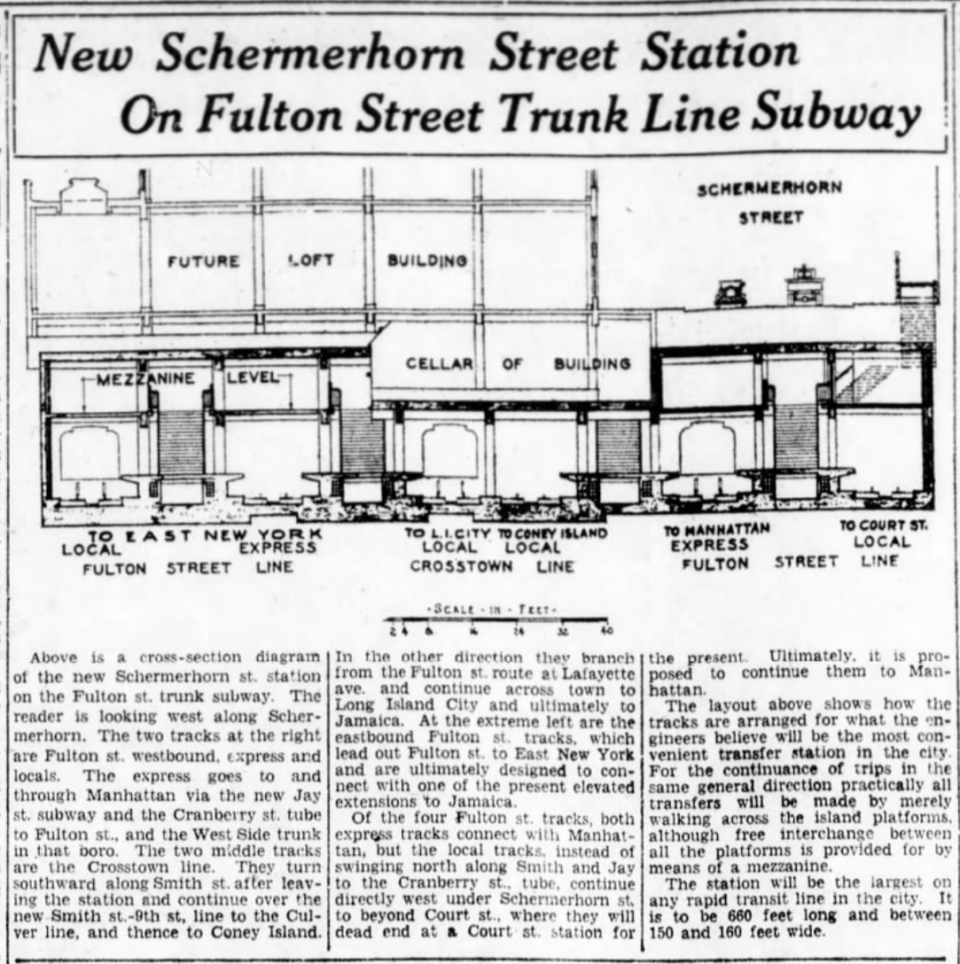

The IND made a similar choice for Fulton St. In Manhattan, the subways had been designed so that local trains terminated in Lower Manhattan, while express trains continued on to the outer boroughs. Elevated service in Brooklyn had been similar, with some trains crossing the East River bridges and others terminating at Sands St. The IND figured the same could work for the new Fulton St Line. The IND designed the Fulton St Subway so that local trains would terminate at Court St station and express trains would continue on into Manhattan. If traffic increased, a new tunnel could be built in the future.

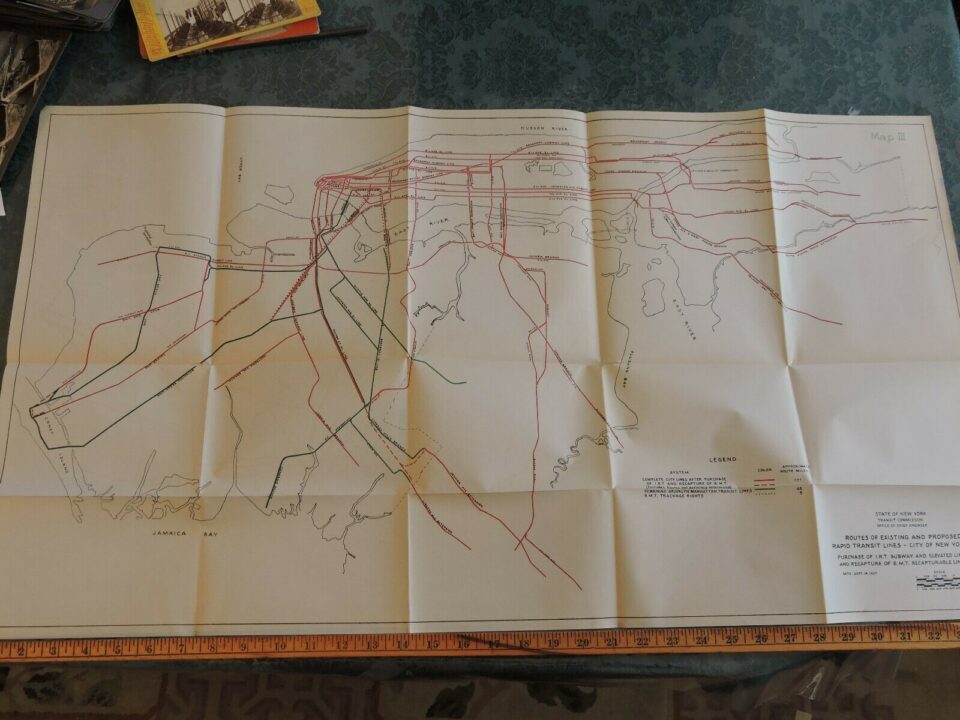

The IND was building their Smith-9th St Line with the express purpose of converting the BMT Culver Line to a branch of the IND to Coney Island. As part of the Dual Contracts, technically the Culver Line was owned by the city, which leased it to the BMT. The IND figured that a similar approach could work for Fulton St, which would be replacing the Fulton St El to at least Broadway Junction, after which point the subway could recapture the BMT Jamaica Line or BMT Liberty Ave Line, both of which had been extended as part of the Dual Contracts.

But while the Culver Line was owned by the city, the elevated tracks along Fulton and Pitkin Streets were owned by the BMT outright, meaning they couldn’t simply be “recaptured”. Not only that, but being older structures, they were not designed to handle the heavier steel body subway cars. The IND knew something had to be done with their new subway, they just didn’t know what.

Planning had gone on long enough and construction began on the IND system in 1925, at St Nicholas Ave and 123rd St in Harlem. In 1927, ground was broken for the Queens Blvd and Smith-9th St Lines. The next year construction began on the Concourse Line and Crosstown Line. Finally, in April 1929, work began on the Fulton St Line.

Six months later the stock market crashed, ushering in the Great Depression.

The Best Laid Schemes

IND planners had spent years working on routes for all of their new lines. The first phase of Fulton St would be built along Schermerhorn St to Lafayette Ave, where the Crosstown Line would branch off, and the Fulton Line would continue to Rockaway Ave. A station at Broadway Junction was planned for the next phase, as the direction of the tunnel would determine the station location.

A month before the stock market crash, the IND had published a wildly ambitious second phase of their plans, forever known as the IND Second System. The plans included extensions of their first phase, along with a massive new trunk system in Brooklyn, the South 4th St Line, which would connect to southeastern Brooklyn, Central Queens, the Rockaways, and South Jamaica. The only plans for the Fulton St Line were to connect with the BMT Liberty Ave Line (the Queens end of the existing Fulton St El), which would be continued east to Jamaica Center.

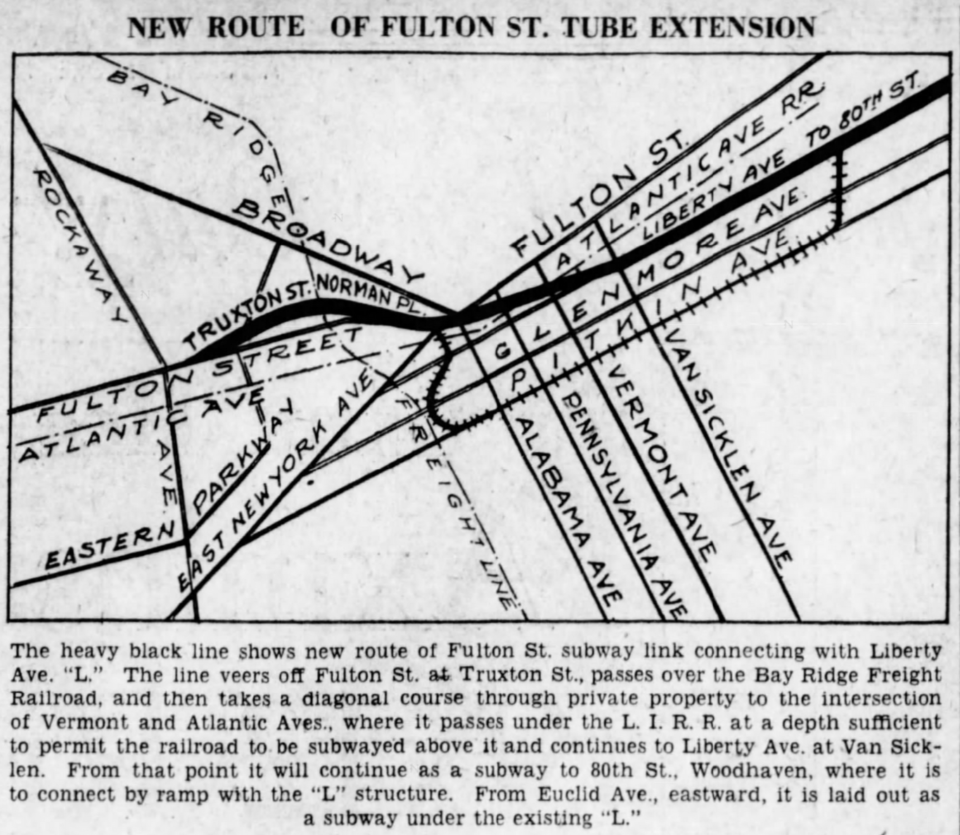

The initial plan for the extension was to have it cross Atlantic Ave, cutting across a few blocks of private property, and run east down Liberty Ave to Grant Ave, where the subway would come about ground and connect with the BMT Liberty Ave Line, which like with the Culver, had been built during the Dual Contracts and therefore could be recaptured.

It should be noted that at this point, not a single mile of the IND had been opened for service. Some argue that the Second System plan was a ruse to raise more money for the first phase which was rapidly going over budget. With the country entering the Great Depression, the Board of Transportation began to focus their efforts on finishing what they started.

The 8th Ave trunk line opened first in 1932, running from 207th St in Inwood to Chambers St. The next year, the Concourse Line opened to 205th St in Norwood, the Queens Blvd Line opened to Roosevelt Ave, the Smith-9th St Line opened to Church Ave, and a small section of the Crosstown Line opened in Greenpoint. The opening date for the Fulton St Line was set for 1934, but the Depression stalled the work.

The city had an ace up it’s sleeve, or more accurately, it had an ace in the White House. President Franklin D. Roosevelt had been the Governor of New York State when the IND broke ground. While in Albany, he signed many bills to help ease the Depression and get people back to work. When he became president in 1933, he turned many of these ideas into his New Deal.

A major element of the New Deal was the Works Progress Administration, which for the first time allowed the federal government to pay for and built large public works. The city, by the leadership of Fiorello La Guardia, was able to take advantage of WPA funds to finish the IND. The Fulton St Line was finally opened to Rockaway Ave on April 8th, 1936. WPA funds also paid for work on the extension of the Queens Blvd Line to Jamaica, which opened in stages between 1936 and 1937, and completing the Crosstown Line.

Initially, the Fulton Line only ran with a single local service between Manhattan and Rockaway Ave, the “A” train. The “C” train would terminate at Hoyt-Schermerhorn during the day, and there was an “HH” shuttle train between Court St and Hoyt-Schermerhorn. Local “A” trains used the local tracks between Hoyt and Utica Ave. Past Utica Ave, they would switch to the express tracks and continue to Ralph and Rockaway Aves. These stations, being local stops, required the building of temporary platform extensions over the local tracks so that riders could reach the trains on the express tracks.

A Choice is Made

The published plans by the IND for extending the Fulton St Line routed it along Liberty Ave. But local business groups balked at the proposed land taking (that is, business owners didn’t want to lose their buildings, but preferred if other homeowners did instead). They argued that the line should follow Pitkin Ave, since the elevated trains were already there. The portal between the subway and elevated train was a particular sore spot, and it was argued that it would cost less to build along Pitkin Ave than Liberty.

The heart of the ambitious IND Second System was the South 4th St Line, which featured a 4-track branch through Bushwick, Ridgewood, Glendale, Woodhaven, and Ozone Park. In Ozone Park the line would split, with one branch turning east to South Jamaica along 120th St and one continuing to the Rockaways. With cost over-runs and the Depression, this entire line was cut.

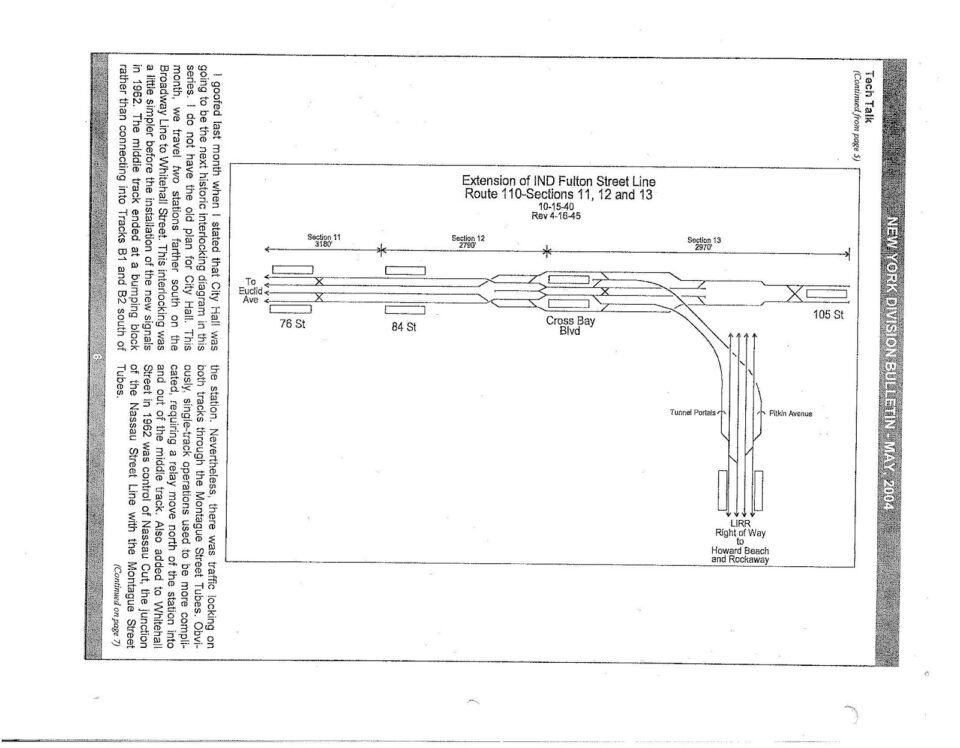

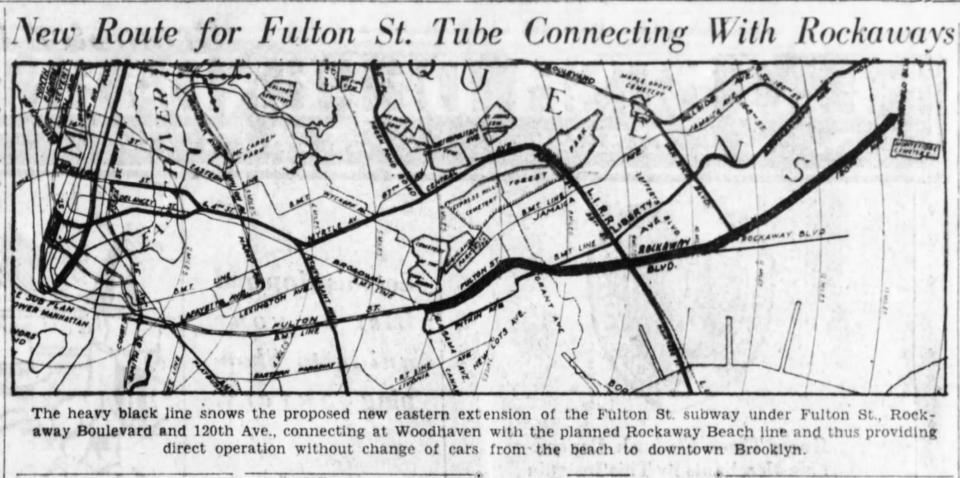

Cutting the fat meant that the branches through southern Queens needed somewhere to go, and the Fulton Line made a fine alternative. The IND proposed to extend the Fulton St Line under Fulton St through Cypress Hills (directly below the BMT Jamaica Line), to Rockaway Blvd, then down Rockaway Blvd to Woodhaven Blvd/Cross Bay Blvd. Here, two tracks would branch off and run to the Rockaways, while the other two would continue along Rockaway Blvd to 120th St.

Running the Fulton St Line so far north angered East NY merchants who would lose service when the Pitkin Ave El was removed. As a compromise, it was proposed to extend service from the BMT 14th St-Canarsie Line (“L” train) along the Pitkin Ave El as a replacement. But this idea was scrapped like so many other IND plans of the time.

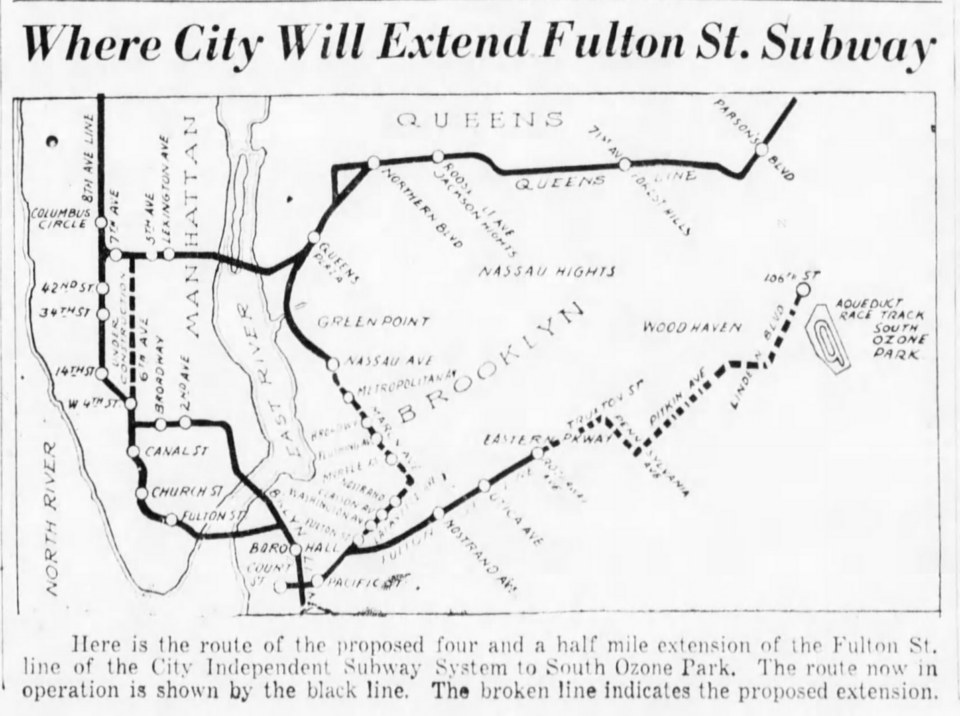

In 1937, the IND relented and finalized the extension to run from Eastern Parkway Extension, under Pennsylvania Ave, and along Pitkin Ave to Cross Bay Blvd. After Cross Bay Blvd, two tracks would continue under the Rockaway Line to a terminal adjacent to the Aqueduct Racetrack, with the other two connecting directly to the Rockaway Line. That is, if the city would ever buy the line from the LIRR. Hedging their bets, IND planners added two small bellmouths to the outside walls of the extension, just east of the Broadway-East NY (now Broadway Junction) station, which would facilitate a future connection to the BMT Jamaica Line.

Work on the extension began in 1938, but was slowed due to the focus by the city to finish the 6th Ave trunk line in Manhattan. Work there was harder than usual given the requirement to keep the 6th Ave El running while excavation was happening underneath. The Fulton St El had been supported in a similar way during subway construction, but the soft Long Island sand was easier to work with than the hard Manhattan Schist, which required blasting.

When the Fulton St Subway opened in 1936, residents immediately called for the removal of the hulking old El. But the city was reticent to do so, since condemnation would mean requiring riders to pay double to transfer between the El and subway. Soon, this would no longer be an issue.

As the new IND began to siphon riders from the IRT and BMT, and inflation meant that the legally mandated 5 cent fare was worth less and less, the private subway companies finally threw in the towel. In May 1940, the three systems were united at last. The city was able to purchase the bankrupt IRT and BMT wholesale, and the city was able to begin tearing down the old Fulton St and 5th Ave Els in Brooklyn. The Fulton St El was torn down between Sands St and Rockaway Ave, where a free transfer was provided to the new subway.

The 6th Ave Line opened on December 15th, 1940, and work shifted to Fulton St. A year later, the Japanese Empire attacked Pearl Harbor and the US declared war on Japan and Germany. Work on the Fulton St Line extension ground on, but as men and materials were slowly shifted to the war effort, work was eventually halted in 1942. Most of the Broadway-East NY (now, Broadway Junction) station was complete, but lacked signals. The additional stations were only shells.

End of the Line

World War II required a considerable amount of materials that would normally be needed for basic maintenance to be diverted overseas. With oil rationing, fewer people were driving, and the subways saw their highest ridership to date. But the greater wear and tear, matched with less maintenance, meant that the systems were in considerably worse shape, given their age, after the war.

The city had only ever run local service on Fulton St, even though there were express tracks. With prospects for subway expansion dimming, some southeastern Brooklyn residents began asking the Board of Transportation to build a line along Utica Ave which would connect to the express tracks. Since the city still planned to extend the Fulton St Line into Queens, this was rejected due to a lack of capacity.

Work was restarted in 1946 and the extension was open as far as Euclid Ave in November 1948. The extension included a large storage yard and maintenance facility, as had provisions for a future extension eastward. Plans at the time still had the line being extended further into Queens along Pitkin Ave, then Linden Blvd. A Second System revision released in 1939 had included the recapture of the BMT Liberty Ave Line, a connection to the LIRR Rockaway Line, and an extension along Linden Blvd to Cambria Heights. Needless to say, the prospects for these extensions were dim.

The city was having a hard time paying for infrastructure, and the money it did get was mostly going to new roads thanks to the work of mast builder Robert Moses. The connection between the IND Smith-9th St Line and the BMT Culver Line had been sitting almost abandoned. The last IND extension built by the city of New York was a one station extension of the Queens Blvd Line to 179th St, along with a large underground storage yard to provide more trains on the line.

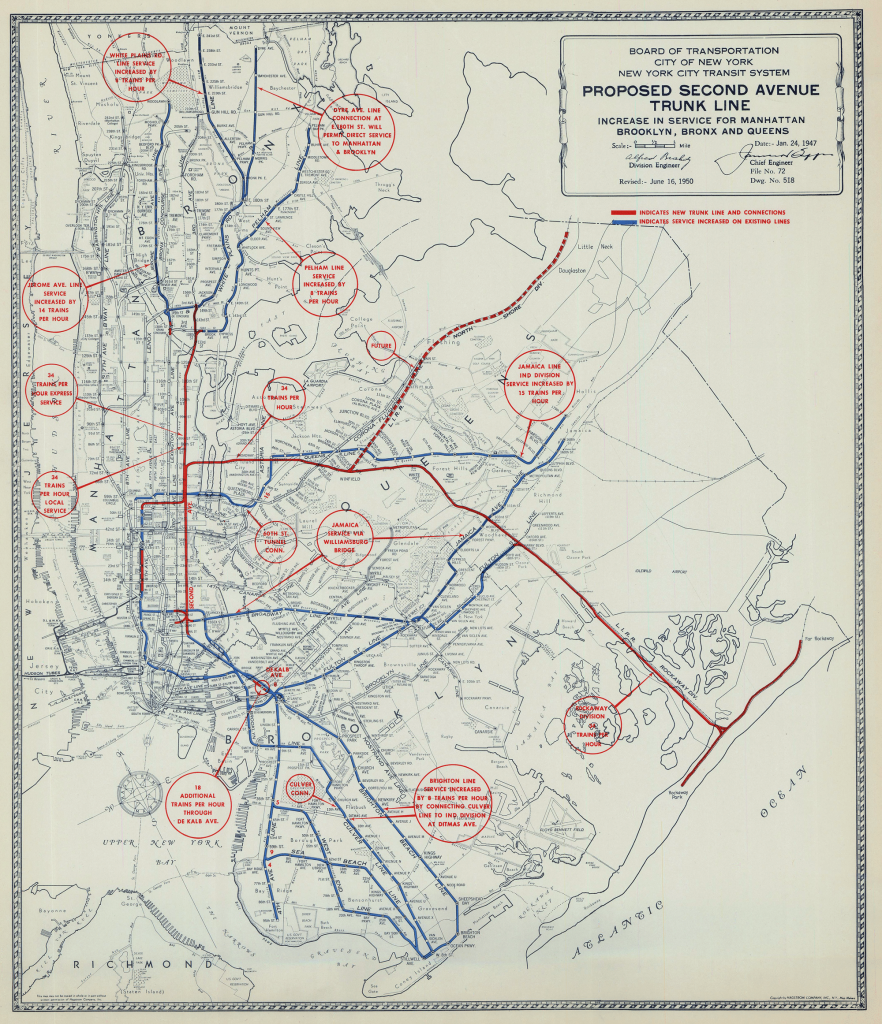

In 1947 the city proposed a new subway expansion program, similar to the IND Second System with lines along 2nd Ave in Manhattan, as well as Nostrand and Utica Aves in Brooklyn. But for Fulton St, all that was proposed was to finally connect the subway to the Liberty Ave El, and extend this along the LIRR Rockaway Line. Any extension further along Pitkin Ave was dropped.

In 1950, after much haggling, the city passed the historic $500 million bond act to raise money for this expansion, but it had all been a ruse. The city spent most of the money on maintenance, extending some subway platforms, finally purchasing the LIRR Rockaway Line in 1952, and the rest was consumed by Moses for his roads.

In 1953, with the city unable to build, the state took over the subways with the creation of the New York City Transit Authority. As a public authority, the NYCTA (or TA as it was commonly referred) could sell bonds to raise funds for needed improvements. These would be paid back by the fares from riders. Once created, the TA set about building long needed connections.

In 1954, the Smith-9th St Line was finally connected to the Culver Line (the older name of Smith-9th St was eventually lost, and the entire line is now known as simply the IND Culver Line). In 1955, a connection was opened between the BMT 60th St Tunnel and the IND Queens Blvd Line to provide more local service. The INDs plan to have the Crosstown local serve as a single local train along both Queens Blvd and to Coney Island via the Culver Line had proven woefully insufficient for Manhattan-bound demand.

In 1956, a new station and ramp was built at Grand Ave, extending the Fulton St Line to finally connect with the Liberty Ave El. It had taken 30 years, but the was finally a direct subway line from Ozone Park along Fulton St. The Rockaway Line was connected directly to the subway. A second connection to the Queens Blvd Line was considered, using the Rockaway Line north of Liberty Ave, but limited local capacity along Queens Blvd prevented this, and the northern tracks were eventually abandoned in 1962.

Plans for extending the Fulton St Line deeper into Queens were still being considered as late as 1963. But by then, focus was shifting towards providing better new service between Midtown Manhattan (which had seen an explosion of growth after the war) and Queens. By the late 1960s, all planning was focused on the 63rd St Tunnel and designing new routes around that.

Potential Meets Reality

While the elevated trains we associate with Brooklyn may have helped the borough develop at the end of the 19th century, they were not passive actors on the urban stage. When subways proved to be a viable alternative, city leaders immediately rose up to call for the replacement of the elevated trains with new tunnels. The private operators, the IRT and BRT/BMT understood that construction of subways was far more expensive than building elevated lines. Since they had to make money on service, it made sense to keep the elevated lines and tunnel only where necessary.

The goal of the IND project was to replace the aging Els with modern subways. The reasoning was two-fold: the IND was legally required to make money within three years, so covering popular service areas was necessary, and the removal of the elevated tracks would improve property values along their routes.

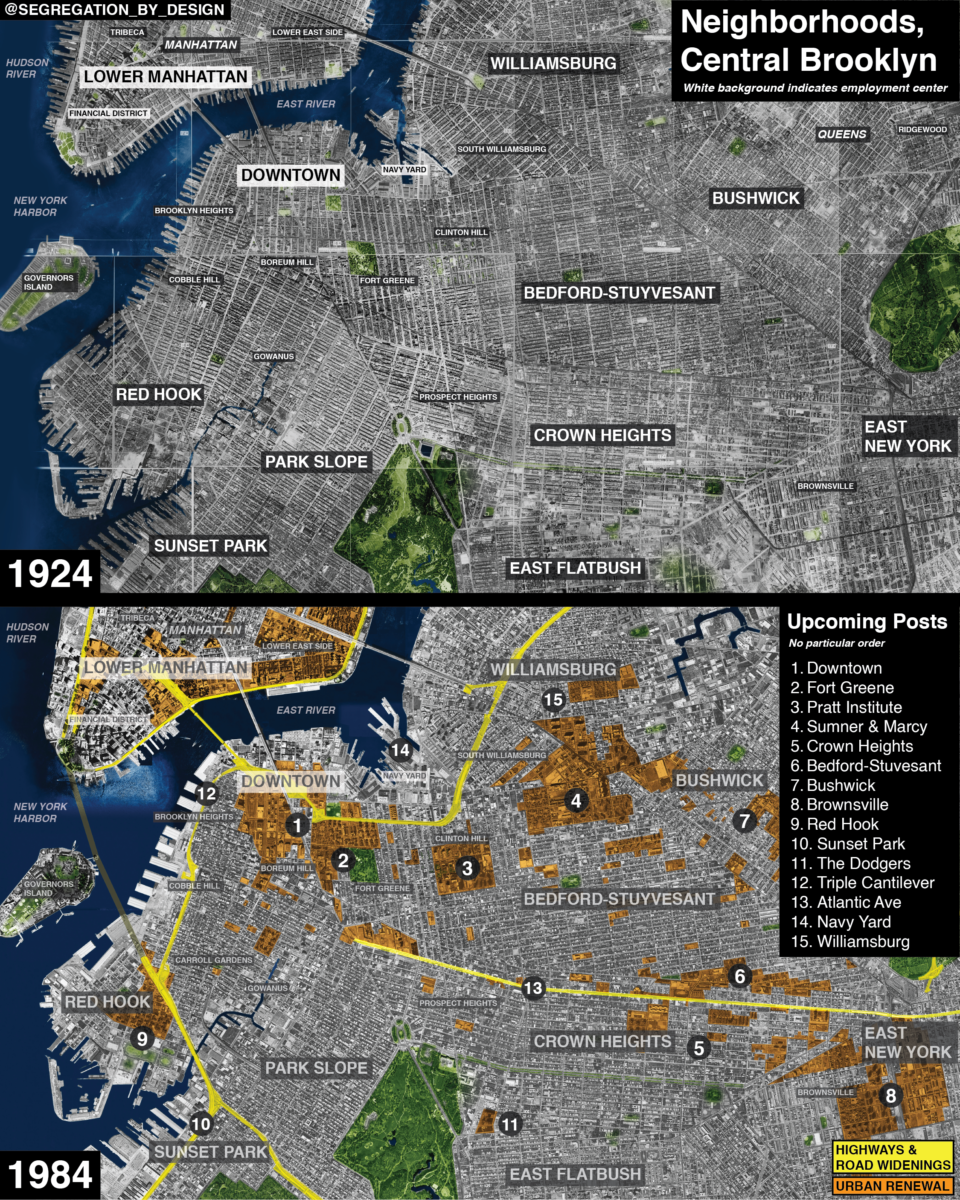

The elevated trains, and later the subways, created a building boom outside the central business districts of New York and Brooklyn. These streetcar suburbs attracted the middle and upper-middle classes with larger homes away from the crowded city. Their former residences, once stately brownstones and row houses, were often cut up into apartments for the lower and working classes. Property owners saw the Els as an impediment to redeveloping these once well-to-do neighborhoods.

Almost all the Els in Brooklyn converged in downtown, meaning that much of the most valuable real estate in the borough was believed to be unnecessarily burdened. Boosters and civic groups clamored for their removal. The new IND lines, and the unification of the subways under municipal control, meant that the impediment to growth could be lifted. Boosters published fanciful renderings showing new skyscrapers rising where Els once dominated the streets.

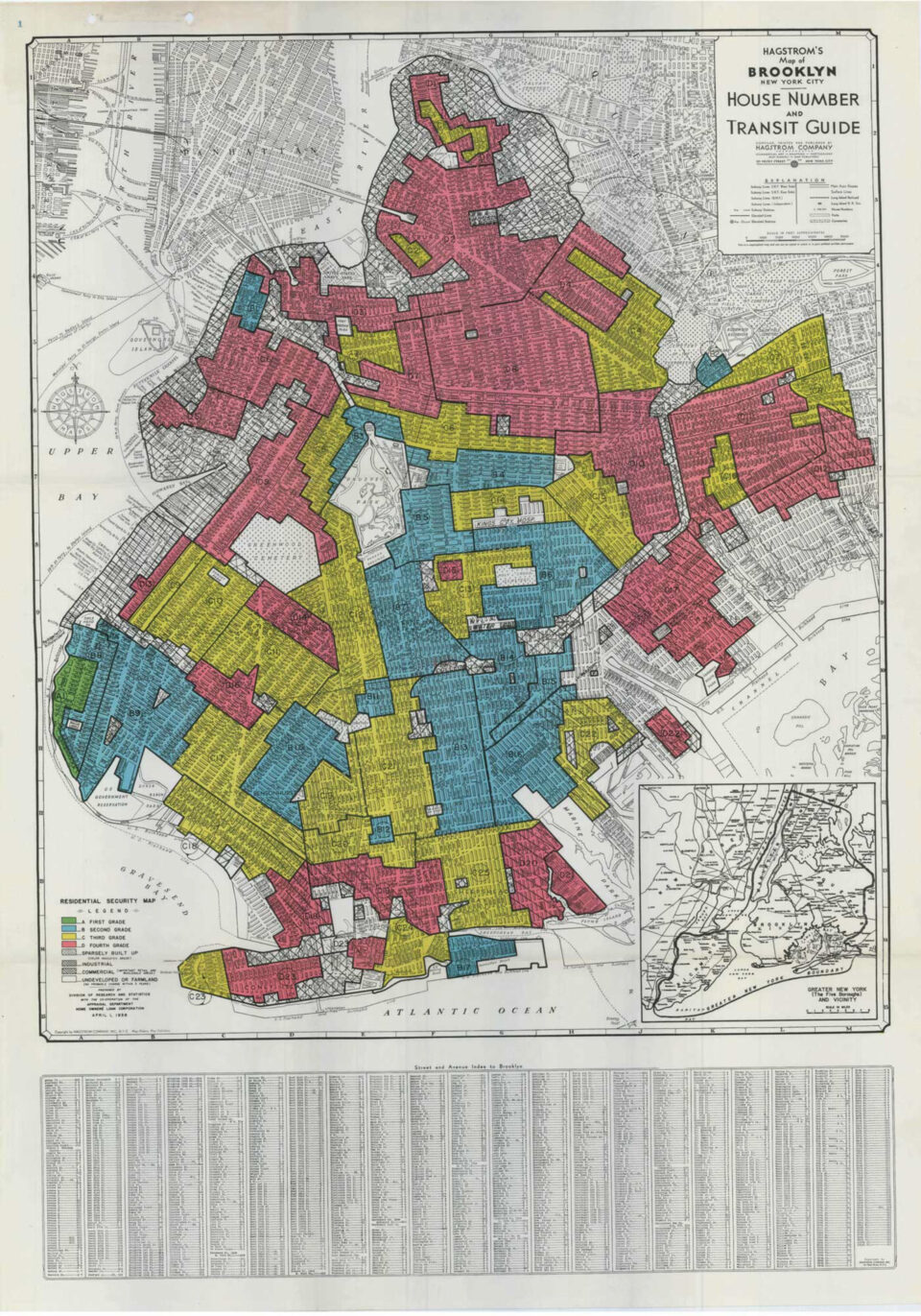

However, forces greater than just a loud, dirty elevated train were at work. In 1934, the National Housing Act was passed which, unbeknownst to most, codified the practice of redlining. Banks created maps of major US cities to determine which neighborhoods were worthy of investment and which ones weren’t. These were said to be based on the quality of the building stock (older buildings needed more investment), but in reality the practice was race based.

The period between 1910 and 1940 was known as the Great Migration, where tens of thousands of black sharecroppers picked up and moved, often entire families, from the farms of the deep south to northern cities looking for better jobs and lives. Being poor, and the bottom rung of the social ladder, they found housing in the older, most depressed areas of the city. Soon, black enclaves began to blossom, famously in Harlem, and in the neighborhoods of Bedford and Stuyvesant in Brooklyn.

All it took was one black person on a street for the entire block to be redlined. In practice, this meant that these once middle class neighborhoods were being choked not by elevated trains, but by racial discrimination and institutional disinvestment. Fulton St was the backbone of Central Brooklyn, and many black families used to find housing and reach the city to look for work. Sadly, many of the working class jobs that had helped so many immigrant groups in the past were beginning to leave the city for the suburbs, or out of state.

After the war, the migration continued, but this time a second migration was starting. Since banks wouldn’t lend to a homeowner in a redlined area, those who could afford to move did so. What they found were new homes, affordable to the white middle class, further afield. Farmland in Queens and Nassau County was ripped up at a record pace to build new housing. These new communities weren’t being designed around trains, but for automobiles and the highways that Robert Moses had built.

What many subway fans fail to realize is that the city also used building the IND as a way to create new arterial roads. Queens Blvd as we know it today was built as the roof of the IND Queens Blvd Line. The 8th Ave Line was slashed through Greenwich Village, extending 6th Ave from Carmine St to Franklin St in Tribeca. East and West Houston Streets were once narrow lanes similar to Bleecker or Prince Streets. The 6th Ave Line was used to transform Houston into an important east-west artery. Fulton St was spared this destruction, but Pitkin Ave was widened between Pennsylvania Ave and Conduit Blvd. Had it been extended, both Pitkin Ave and Linden Blvd in Ozone Park would have been widened, and many more homes would have been demolished.

The conditions of the inner city only worsened. The population of Brooklyn peaked in 1950, at 2.7 million residents. It bottomed out in 1980, with 2.2 million people. In 2020, the population has stabilized at 2.55 million, but is still 178,000 people short of peak (the population of a small American city in itself.)

The rejuvenation that the removal of the Fulton St El was promised to bring didn’t happen for 50 years. Today, gentrification has begun its seemingly unstoppable march down Fulton St, first in the 1960s and 70s as the middle class began to return to Brooklyn Heights, then in the 1980s and 90s in Fort Greene and Clinton Hill, and today as Bedford-Stuyvesant is turning over.

Ironically, redlining may be partially responsible for Bedford-Stuyvesant being the desirable neighborhood that it is becoming today. Lack of bank loans meant that many of the old brownstones weren’t torn down to be replaced with modern apartment towers. Though urban renewal certainly left its mark on Central Brooklyn, Bedford-Stuyvesant is home to more blocks of impressive brownstones than the Upper East or West Sides of Manhattan, which saw massive redevelopment, both private and public.

East New York, in particular, was hard hit from white flight. The neighborhood was never as well-to-do as Brownstone Brooklyn, and had worse housing stock to begin with. As white lower-middle class families moved out, often from aggressive realtors who would move in a single black family to scare off the white families in a practice known as blockbusting, the neighborhood quickly turned into a no-mans land of burnt out buildings and empty lots, and poverty was extreme. Much like in the South Bronx, if you couldn’t get a loan, and couldn’t sell your property, you could always burn it down for the insurance money.

The original hopes of Brooklyn boosters for a return to prominence for the neighborhoods along Fulton St were dashed by a cocktail of state and federal policy larger than they could have imagined. Ironically, the racist institutional policies of the mid-20th century have finally created the gentrification which is now happening along the corridor. While the disinvestment was the cause of the creation of the black ghettos of Central Brooklyn, the area became a home for black and African families. Those who were able to buy their rundown homes, and fix them up with their own money, are often selling them to new white families, attracted to the area for its beauty, culture, and access to the city via the Fulton St Subway.

The Fulton St Subway never lived up to expectations. Today we face long wait times because service has to be split between local and express, which both use the Cranberry St Tunnels under the East River. The local tracks were planned to be connected to the 2nd Ave Subway, but we all know how long that’s taken. Subway fans often like to dream about what the city could have been had more subway lines been built. It’s hard to say what Brooklyn would have been like if Fulton St had been extended deeper into Queens. Most likely, it would probably be the same. Our infrastructure doesn’t exist in a vacuum, and Central Brooklyn was home to some of the most powerful societal forces of the 20th Century.

It’s unclear what the future may bring for Fulton St. The MTA is planning on installing new CBTC signals along the line, so it can run trains closer together. But it will still only ever max out at half the capacity it’s built for unless a new tunnel to Lower Manhattan is built. If such a tunnel is to be built, it would act as a nitro boost to an already hot wave of gentrification. Building the last leg to Linden Blvd doesn’t make much sense when the elevated Liberty Ave Line, only a couple blocks away, sees such low ridership. It’s a chicken-and-egg situation, unfortunately; Fulton St can’t support better service until the subway is expanded, but that won’t happen with low ridership due to poor service.

Coda

No post about the IND Fulton St Line would be complete without mentioning the 76th St station. For those who aren’t obsessed with all things NYC transit, 76th St station is a myth that claims that when the Fulton St Line Extension was built to Euclid Ave, it included an additional station beyond Euclid Ave, at 76th St. The story claims that the station was filled back in after it was clear there wouldn’t be any more work on the extension to Linden Blvd.

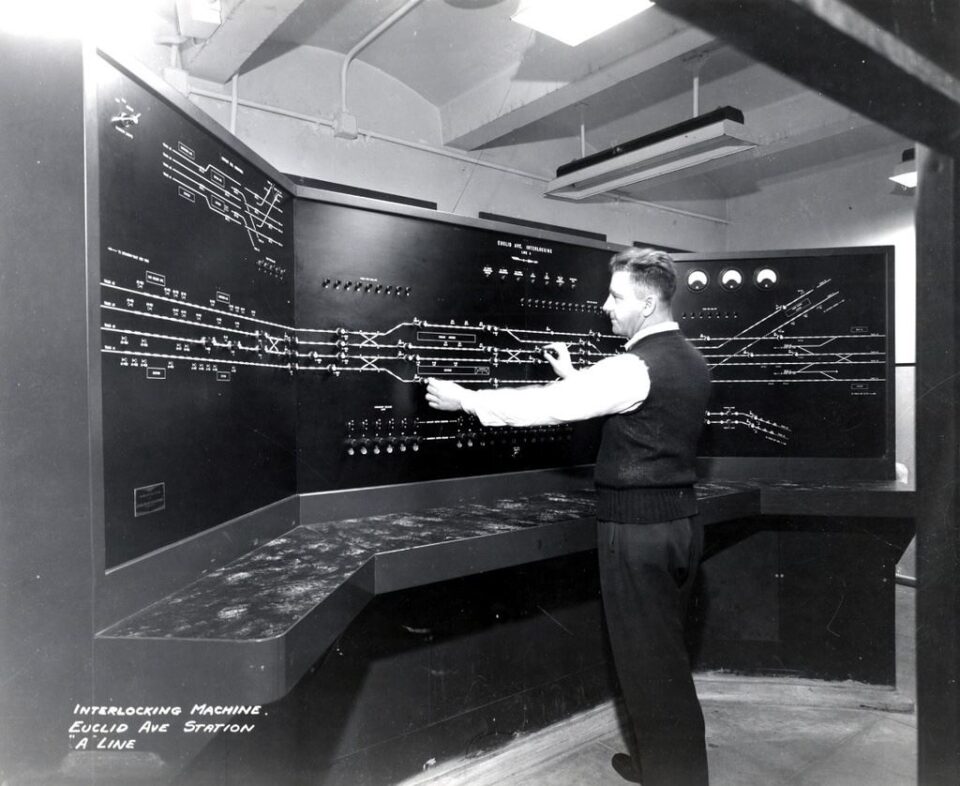

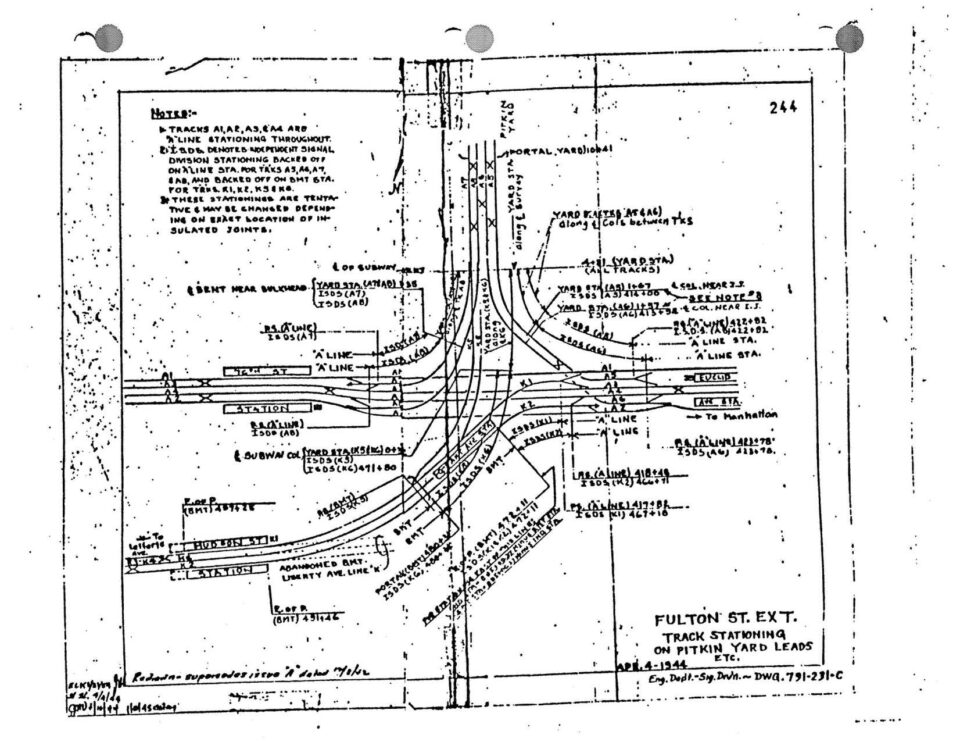

The source of this story comes from an April Fools post by Joseph Brennan, who hosts a website dedicated to abandoned subway tunnels. The image above, which is real, shows the switchboard at Euclid Ave. Here, the operator controls the complex interlocking that allows trains to move through the station, either on their way into Queens, or to and from the Pitkin Yard. The board clearly shows Euclid Ave and the Grant St station which branches off to the top right. What you also see is the layout for the second phase of the extension to Linden Blvd, which was never built. Here is labeled the 76th St station.

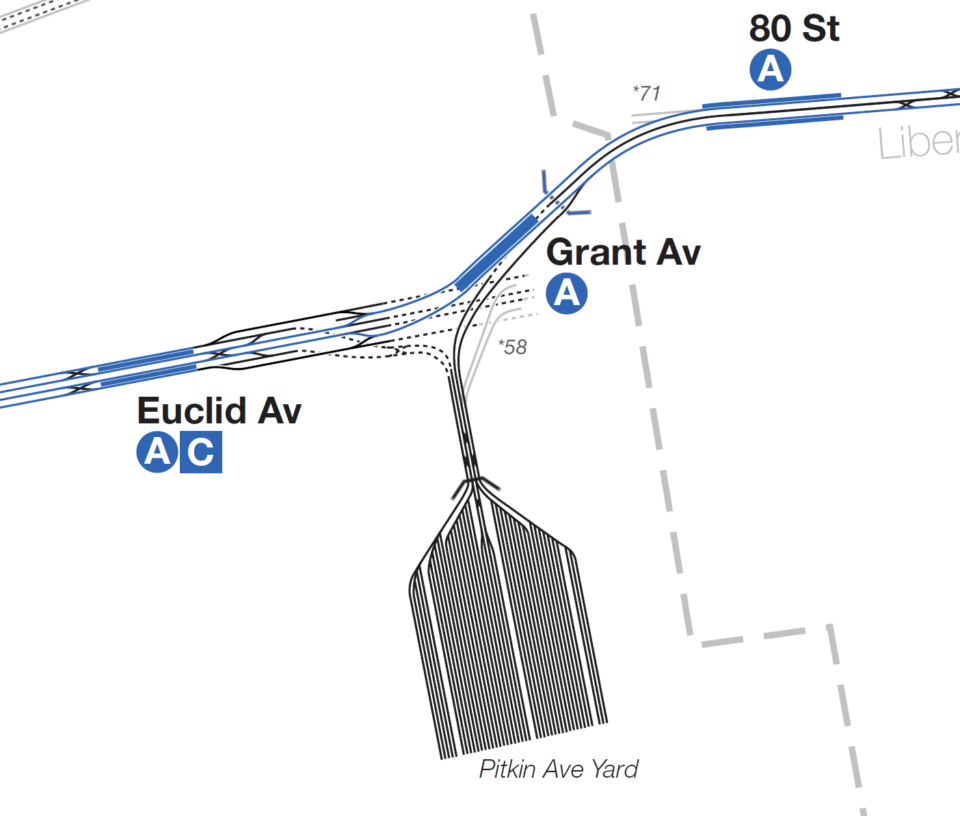

The IND was famous for building tunnels and parts of stations that went nowhere and were unfinished, work for a future generation to pick up from. The tunnels past Euclid Ave do, in fact, exist and remain unfinished. The section of track past Euclid Ave is especially complex. Here, the 4-tracks of the main line continue east, while 2-tracks rise up and connect to Grant Ave station, which continues on to Lefferts Blvd and the Rockaways. In the middle of all this, each track branches off to connect to yard leads, so that any train, from any line, in any direction, could access the main storage yard for the line.

In order to design this complex network, planners had to know where the tracks would go from all angles. While me might think of tunnels as simple holes in the ground, in reality a structure like this is more like its own building, with different floors and access points, just underground. Anything that was built needed to account for what would be added later.

While there are images and maps of what the entire complex would look like, in reality, the city only built the bare minimum of what was required, with space left over for the extension. The four main line tracks do continue east, but only for a short bit (to about Eldert Ln). There are ramps built for the yard connection to the east, but no tracks. Urban explorers have documented the area thoroughly and report that there is nothing down there but a cement wall.

But how do we really know what’s down there? Well, we don’t. But let’s think about it: every time there was work done for a new tunnel, it was news. Even today, papers love to talk about infrastructure projects, especially about how they take too long and cost too much. There has never been a word about 76th St or any work on tunnels past Euclid Ave.

Construction workers don’t just build whatever they like. There are contracts and blueprints that need to be followed to the letter. Each section of the subway (from 1900 until today) was built in small sections that each had their own contract. No contract was ever let for the section which included a 76th St station.

Most NYC subway tunnels were built using the cut-and-cover method, meaning they dug up the street and built the subway roof which doubles as the street bed. Because the tunnels are so close to the surface, ventilation and emergency exits are mostly in the form of grates on the sidewalk. If one walks down Pitkin Ave today you will see these grates running all the way to Grant Ave. Then they stop.

Building subways like this means that the buildings which line the street need to be either supported or demolished. The IND had no qualms about taking private property, and the parking lots around Grant Ave are a perfect example of this. But look closer and you will see that the city made smaller changes too. Pitkin Avenue runs from Eastern Parkway in Brooklyn all the way to the Aqueduct Racetrack in Ozone Park. It has differing widths along its run, but from Eastern Parkway to Pennsylvania Ave it’s 40 feet wide. From Pennsylvania Ave to Conduit Blvd (the stretch along which the Fulton St Line is built) it’s 50 feet wide, and originally had space for four lanes of traffic. Beyond Grant Ave, it narrows again and has space for only two lanes.

Had the city built tunnels past Grant Ave, especially a station, then Pitkin Ave would look very different than it does today up to about 78th St. But the most important fact to consider is the one of basic funding. The city was struggling to build anything after the war. Mayor Dwyer was able to get the bare minimum to finish the subway, which had been sitting half built since 1942. The city couldn’t even afford to build the small connections between the IND and BMT at Church Ave, or even to the Liberty Ave El in Ozone Park. Why would they build an additional 1,500′ of track and station? Not why, but how?

No matter. People will believe what they want. Maybe it’s just more fun to imagine a world of unrealized potential under our feet to distract us from the reality that we have all but forgotten how to build transit anymore.

Mr. Lynch – simply a superb work of research and history. As per usual! Just fantastic and a really interesting read. Thank you.

One minor quibble – the United States of America declared war on Japan on December 8, 1941 (not 1940), and Germany and Italy then in turn declared war on us. Only after this did Congress declare war on Germany (on December 11, 1941).

Wow, how’d I mess that up? Thank you!

Edit: The line in question has been fixed.

I often take the Fulton Street line home from school and it always feels so empty, especially since I’m at a local station. This is enhanced by relatively lackluster maintenace and poor insulation from the cold at many stations. One question I have is Fulton Street (lower Manhattan) seems really tight and tiny for IND, especially considering when they built the line it was right in the heart of the CBD. Any idea why this is?

I actually really like your idea from another article of sending Broadways locals down a new tunnel through Court St, and have Nassau St go via Montague. Unfortunately, for the MTA, the biggest priorities for expansion always have to do with solving an overcrowing issue, and the Fulton St line still has a lot of capacity.

I’m not a 76th Street believer, but I do wonder if there is any NYC subway infrastructure, however small, that has just been lost to history; ik this has happened in London but NYs system is newer and generally very well documented.

RE: Lower Manhattan Fulton. Probably because the streets down there are so narrow. The platform isn’t that narrow, especially compared with other stations down there.

It’s notable that you mentioned Mayor Hylan’s animosity towards the private subway companies. I believe he was a key player in mixing the Staten Island Tunnel after it got started.

*nixing the Staten Island Tunnel.

There was a lot more at play there. The high cost was one thing, but worse, the state wanted a tunnel that could be used for freight as well and the city/state couldn’t agree. It also didn’t help that the BMT 4th Ave Line was fucked, with low capacity and high ridership. Connecting SI to 4th Ave is the simplest way to do it, but the tunnels just couldn’t handle it. Funny enough, I was just tonight going over the same old Brooklyn Daily Eagle papers from that time and found where the SI Borough President proposed the SI tunnel via the IND Culver Line (This was included in the 1939 IND Second System). The Board of Transit wasn’t hot on the idea, but included it for political support.

Being a rockaway resident and looking at the older maps is never easy, why does the Mta hate us so lol