Students of New York history often know that the subway we use today was the result of three private companies competing with one another until they all went bankrupt and were merged. Often overlooked is the fourth subway company, one which almost predated the original subway entirely. It’s still very much in use today, though most New York-centric residents don’t often think about traveling to New Jersey unless they are going to Newark Airport or MetLife Stadium.

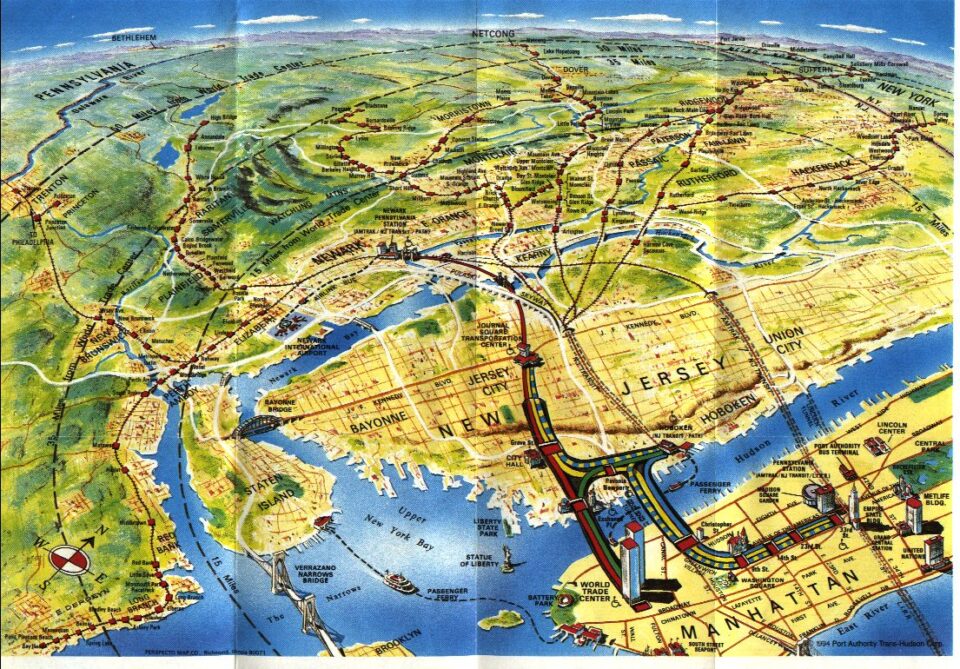

What we know as the PATH was originally the Hudson & Manhattan Railroad (H&M). While this system may seem like the diminutive little brother of the NYC subway, it was the first tunnel built below the Hudson River (predating the Pennsylvania Railroad), and for decades the best way for travelers from points west to enter Manhattan.

The H&M even outlasted the private subway companies, staying private (though liming along) until 1962. As part of their deal with New York and New Jersey to get the rights to build the World Trade Center in Lower Manhattan, the Port Authority took over operations on the H&M, rebranding it as the Port Authority Trans-Hudson, or PATH.

Designed primarily to link railroad terminals on the New Jersey side to the central business districts in New York, the decline in rail traffic during the post-War years, as well as the decline in shipping in Jersey City and Hoboken, decimated ridership and jobs along the New Jersey waterfront. In the 1980s and 90s, steps were taken to redevelop the waterfront using the PATH as a transit backbone, and one only needs to look across the Hudson at the ever-growing skyline of Jersey City to see how well that worked out.

Though still overshadowed by the unrealized ambition of the IND Second System, both the H&M and PATH companies proposed expansion of their railroads. Additionally, various planning commissions and advocates have proposed extensions or additional lines. With overall rail transit on the New Jersey side of the river lacking (or rather, more focused on the commuter from further inland), many have wondered why the PATH has remained such a small part of the overall transit ecosystem.

Haskins and the Hudson

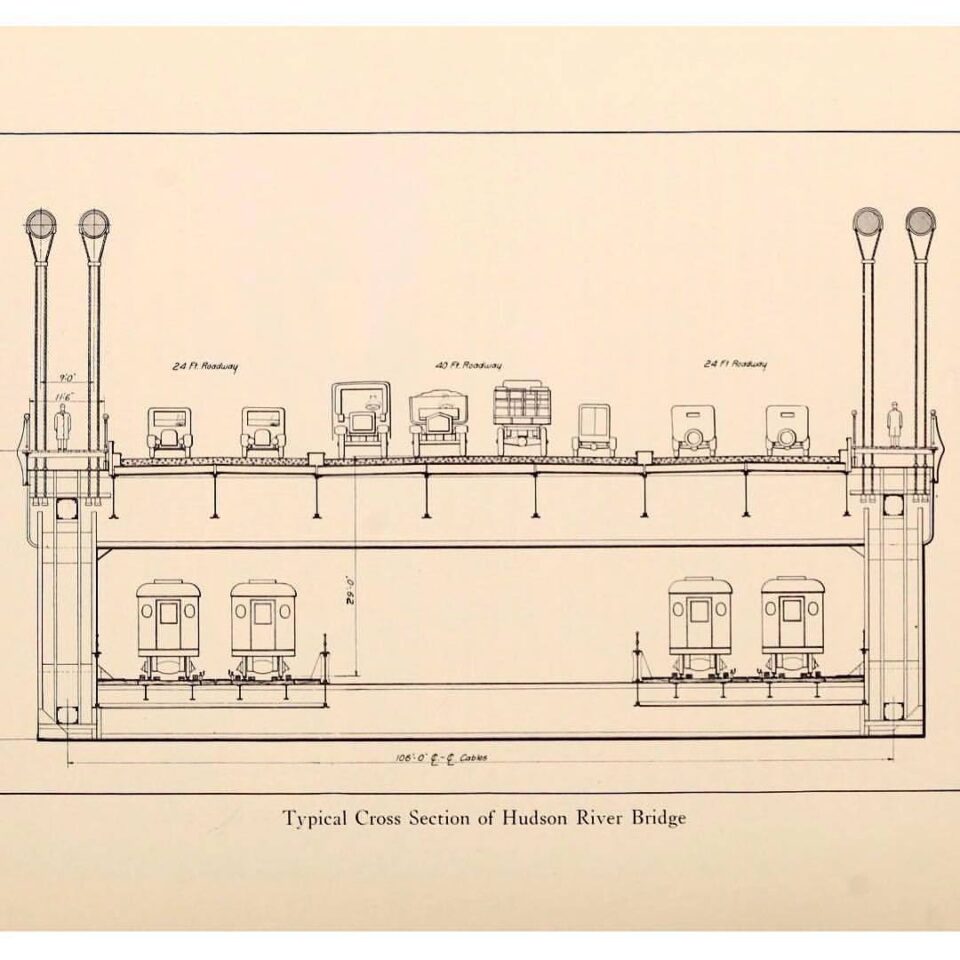

Railroads in the late 19th Century were the tech giants of their day. These were some of the most powerful and wealthiest corporations in human history. But even they dared not attempt to span the mighty Hudson River. While bridge technology was advancing with the development of stronger metal alloys, existing crossings were relatively short. The Hudson River was over a mile wide between Jersey City, where most of the large railroads terminated, and the banks of Manhattan Island.

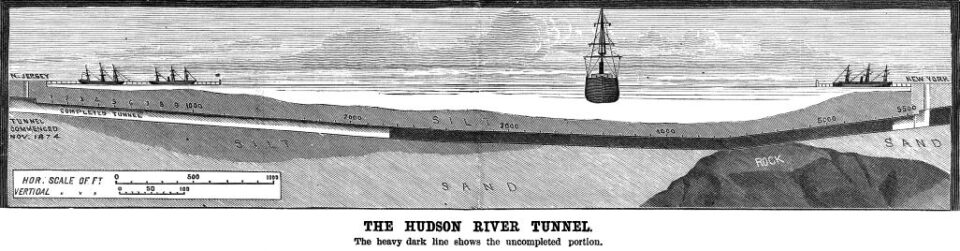

Bridges had been proposed, but these needed to be so gargantuan that none got off the drawing boards. The Hudson River was one of the most important shipping lanes in North America, and nothing could be built that would block this traffic. That meant only tunneling below the river bed would be feasible, and no tunnel of such size or scope had ever been built. In stepped Dewitt Clinton Haskin.

Dewitt Clinton Haskin was born in 1824 in Rensselaer, NY. He was named after DeWitt Clinton, NY State Senator, NY City Mayor, and NY State Governor who is most famous for building the Erie Canal. No doubt Dewitt Haskin was inspired to conquer nature by his namesake. Haskin began his railroad career working on the construction of the California Pacific Railroad after the Civil War.

After this success, Haskin believed that he could be the first person to connect Manhattan Island to the mainland of the continent with a tunnel. Haskin looked at the silt and muck of the river bottom and realized that with the weight of the water above it, he could excavate a tunnel using compressed air to stabilize the work long enough for workers to build the tunnel walls. He had taken inspiration from another crossing going up along the opposite shore, a bridge between Manhattan and Brooklyn; The Brooklyn Bridge was using compressed air to build the foundations of the bridge towers.

Haskin proposed two single-track tubes to be built between New Jersey and New York. He selected sites on both shores and dug deep shafts straight down. His plan was to work from both sides of the river and meet in the middle. Digging was done by hand. The compressed air proved more problematic than anticipated; The pressure was not always strong enough to prevent cave ins, and when workers left the underground atmosphere too quickly, nitrogen bubbles would form in their blood, causing extreme pain. This was known as caissons disease, or as we know it today, the bends.

By 1883, only 1,200 feet of one tunnel had been constructed on the New Jersey side, and Haskin was bankrupt. A few years later, a British company attempted to pick up the project, but they too ran out of funds. By 1893, 20 years had gone by with little to show.

The McAdoo Tubes

William Gibbs McAdoo was only a child when Dewitt Haskin began his attempt to burrow beneath the Hudson River. A lawyer by trade, McAdoo got his first experience with mass transit in the 1890s, when he lost most of his money attempting to electrify the streetcar network in his hometown of Knoxville, TN. In 1892, McAdoo moved to New York City to start a securities firm. No doubt, this is when he would have first been introduced to the Hudson River tunneling attempt. McAdoo attempted one more time to buy out the Knoxville streetcar system, but was thwarted by an Ohio businessman.

Undaunted, McAdoo returned to New York and decided to pick up the bankrupt Hudson River tunnel. McAdoo formed the Hudson & Manhattan Railroad to finish work on the tunnel. Tunnel construction had evolved in the previous 20 years, and the compressed air that Haskin had used was replaced by a tunnel shield (a device that did exist at the time, but had been rejected by Haskin.) The tunnel shield would support the front of the tunnel, where workers would remove silt and rocks. Once the shield excavated a few feet, iron ring segments would be placed behind the shield, forming the walls of the tunnel. The shield would then be jacked forward, using the newly placed ring segments as support. This method is still in use today on tunnel boring machines.

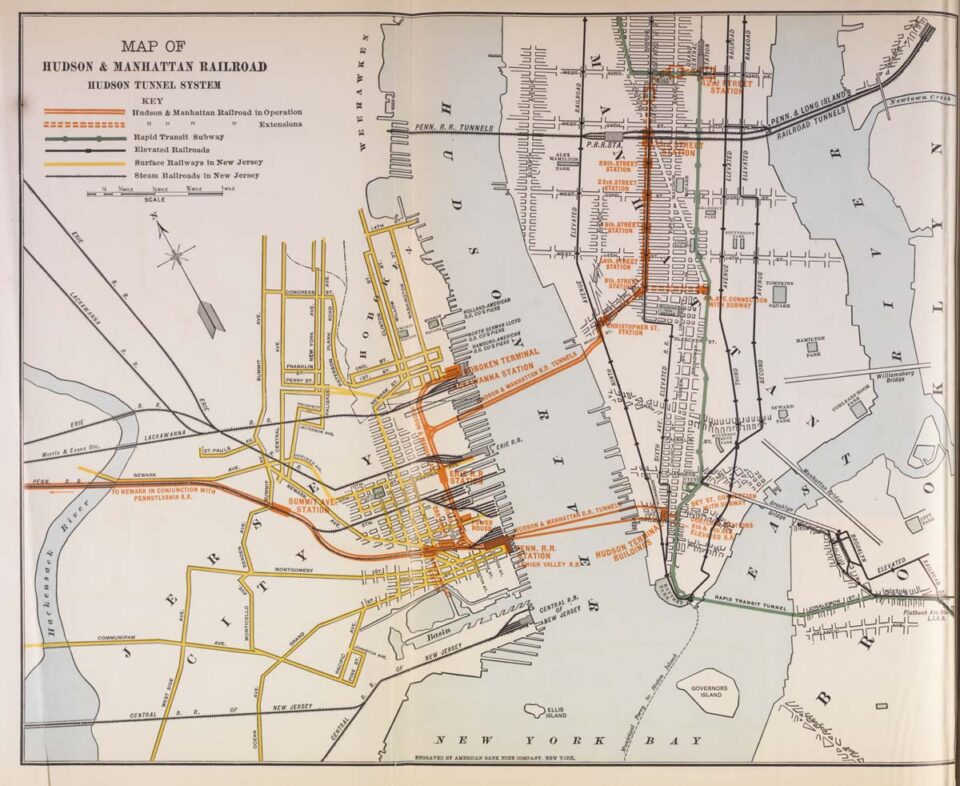

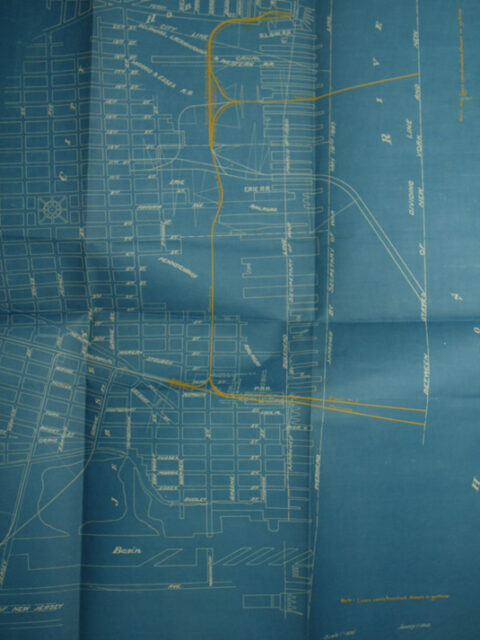

The Haskin plan initially called for two single tubes. McAdoo realized that the growing city needed more than just a single crossing. Even before the completion of the original tubes, McAdoo proposed a second set between Jersey City and Lower Manhattan. These new tubes would henceforth be known as the Downtown Hudson Tubes, while the original ones would be the Uptown Hudson Tubes. In 1904, while construction of the tubes was still ongoing, McAdoo developed a network of connecting tunnels on either side of the river. The New Jersey side would link the major railroad terminals together, while the New York side would consist of two terminals (one downtown and one uptown).

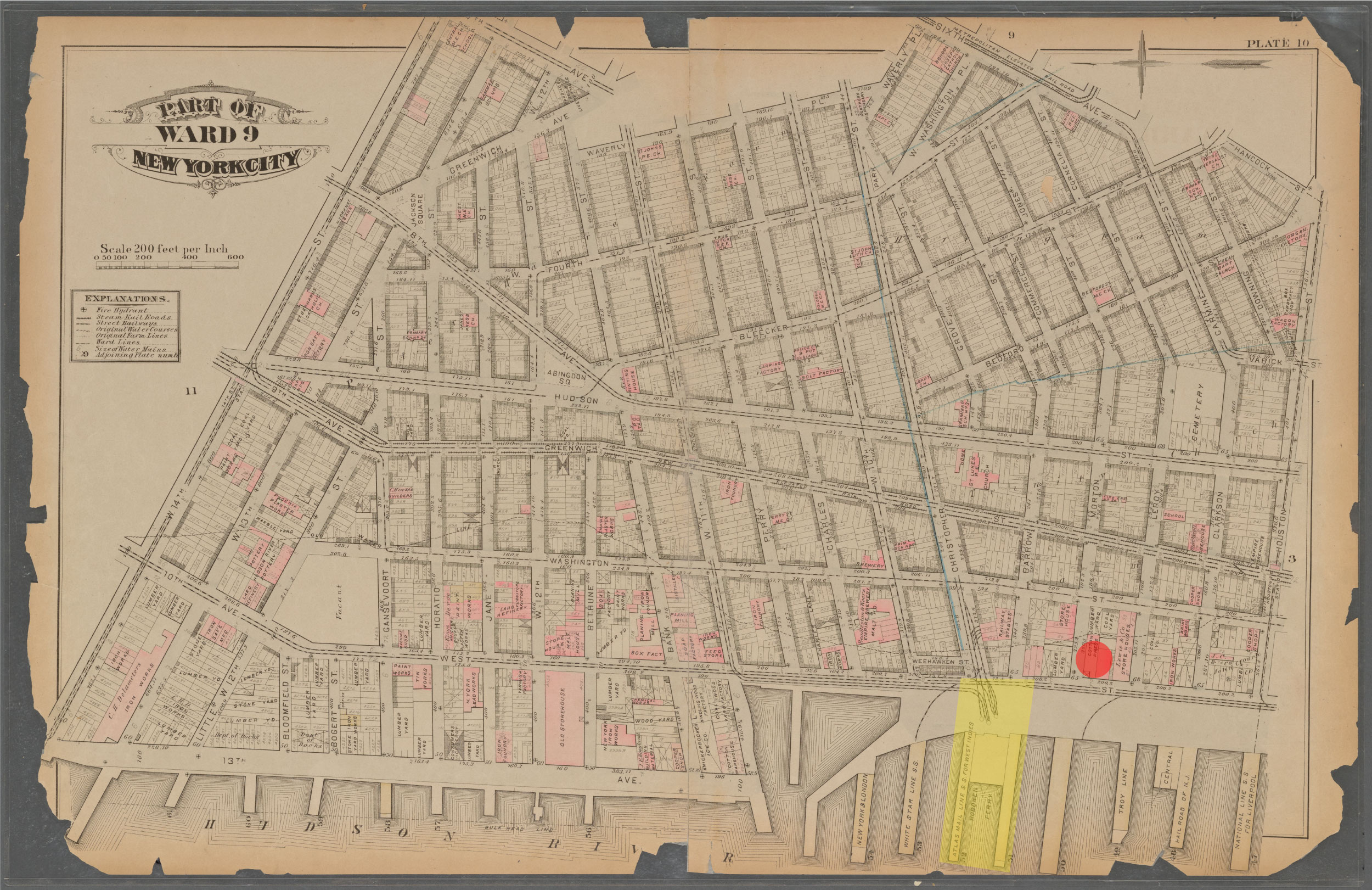

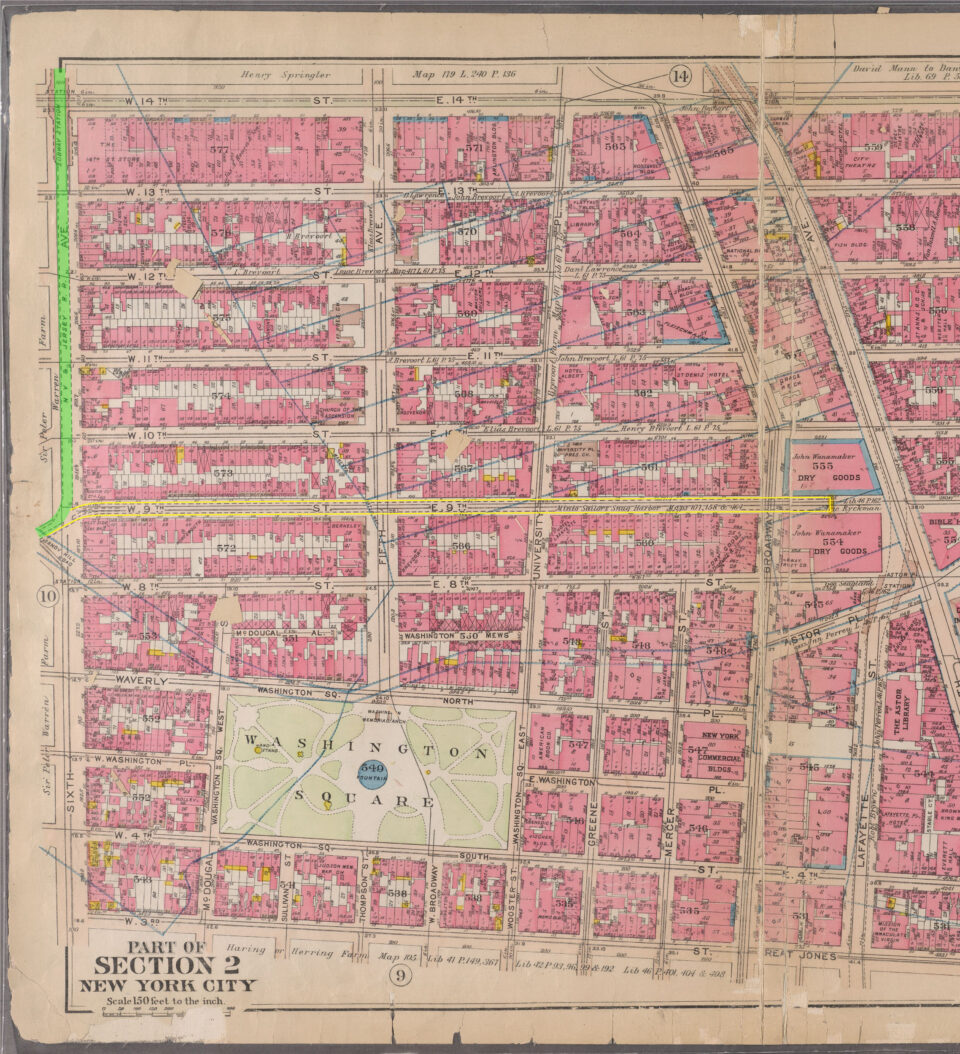

A question that has always gnawed at me is about the location of the Uptown Tubes. The tubes enter Manhattan at Morton St, which itself only runs less than a half mile until it ends at Bleecker St. The tunnels themselves turn north under Greenwich St, then northeast under Christopher St. But Christopher St itself runs to the river. So why didn’t Haskin just build the tubes directly to Christopher St? In his own words:

“Upon the New York side this [location] was governed primarily by the fact that it should be so situated as to be easily reached from the centre of the city, and yet the site should not be in a neighborhood in which the land damages would be so great as to be in reality prohibitory. Upon the other side of the river it had to be so located that the great railroads having their termini there could acquire access to it at a minimum cost.

After a careful examination of all the questions involved, the tunnel was finally located on a line extending easterly from Jersey Avenue (Jersey City), on Fifteenth Street, to Hudson Street, about 3,400 feet ; from this point it curves five degrees northward to the New York City bulkhead line at the foot of Morton Street, about 5,500 feet, and thence again slightly southward about 4,000 feet to the eastern station. As will be seen by consulting the accompanying map, this line places the eastern end in one of the best locations in the city, and also furnishes the most convenient point upon which to concentrate the various railroad lines upon the New Jersey side with the least possible injury to existing interests. “

Source: Tunneling Under the Hudson River 1885

Railroads in the 19th Century weren’t really “planned”, so much as they were just built. Today, if you want to propose a new line, you do surveys to figure out the best possible route, and then look for financing. Back then, it worked the other way around. A railroad would set out to connect Point A to Point B. When financing was secured, then the engineers and surveyors would head out and figure out just where the line would be built.

Haskin didn’t plan his tunnel as part of a larger network. Instead, he was more focused on proving that it could be done in the first place. No mention of integration with other railroads is mentioned. In fact, the word “station” is hardly mentioned either. The idea was to get the tunnel open, and figure out the rest later. Morton St won out over Christopher St for the most New York reason ever: cheaper real estate.

In the 1870s, the end of Christopher St was home to a large ferry terminal owned by the powerful Delaware, Lackawanna & Western Railroad, which had its main rail terminal directly across the river in Hoboken. Of all the large rail terminal buildings that once lined the New Jersey waterfront, the Lackawanna is the only one still in operation today through New Jersey Transit (though the current building was built in the 1890s). Haskin couldn’t strike a deal with the railroad, so he had to work around them. While Christopher St would have been the ideal landing for his tubes, the railroad would never have allowed him to disrupt their operations.

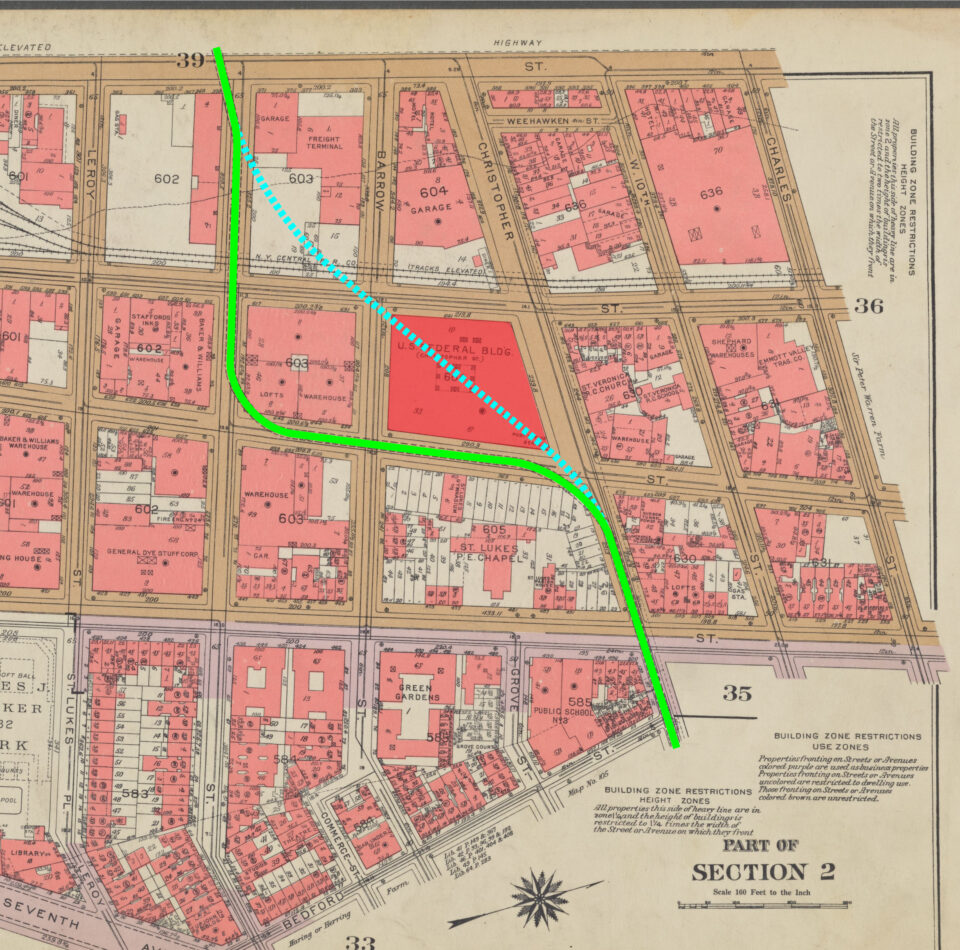

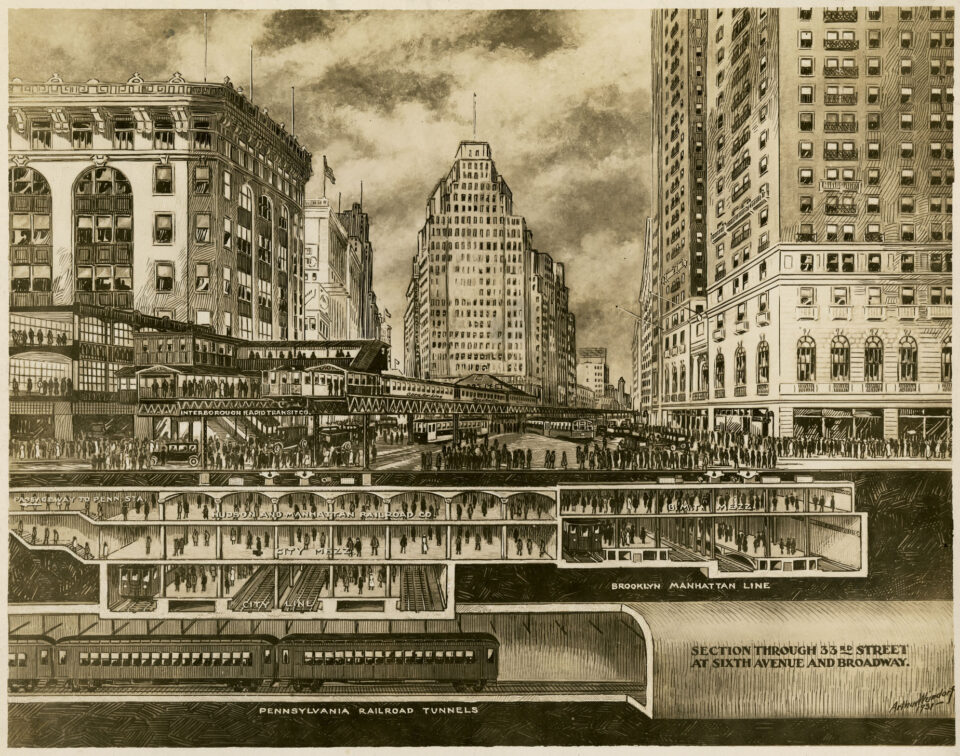

When the McAdoo took over the project, he understood the need to connect the tubes to a larger network. At the time, 6th Ave was the shopping hub of the city. Christopher St ran directly into 6th Ave, so the H&M ran added a dog leg to get the tunnels up to Christopher St via Greenwich St. At the time, the concern was that the tubes would interfere with the large foundations of the US Customs building (which still stands today as the Archive apartments). While these curves are tight by modern standards, they were more generous than some elevated or streetcar curves at the time.

Stations were added at Christopher St/Greenwich St and 9th St/6th Ave. At the time, 9th Ave El trains ran along Greenwich St and had a station at Christopher St, and 6th Ave El trains had a station at 8th St, providing connections to the rest of Manhattan.

Test trains began running in 1907, with revenue service between Hoboken and 19th St/6th Ave starting on February 26, 1908. Service would be extended to 23rd St in June, and the Downtown Tubes would open with service to the Hudson Terminal (located at Cortlandt and Church Streets in Lower Manhattan) in July 1909. In 1910, an extension from Exchange Place to Grove St opened. A year later, this was extended to the Manhattan Transfer station in Harrison, NJ. This station was not accessible from the street, and was designed to facilitate transfers to steam powered Pennsylvania Railroad trains that would not be able to cross the Hudson River.

In October 1911, the line was further extended to Newark, NJ, though not where the present station is today. The line continued along New Jersey Railroad Ave and crossed the Passaic River south of Rector St, Newark. The Park Place terminal was located at Park Place and Center St. In November 1911, the uptown line was extended to the 33rd St terminal at 6th Ave, and infill station at Summit Ave, now Journal Sq, opened in 1912, effectively completing the railroad.

PATHs Not Taken

Grand Central and 9th St

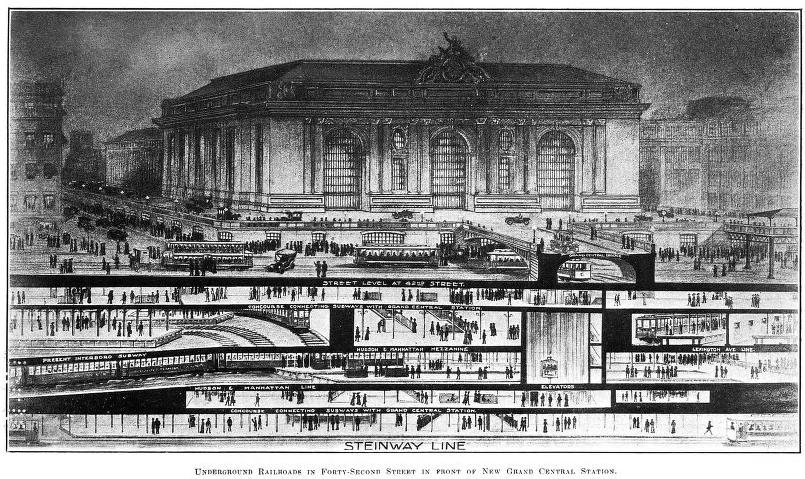

The H&M didn’t open in a vacuum. The Interborough Rapid Transit Co. (IRT) had opened the first subway in NYC in 1904. The general design philosophy of the H&M was to connect riders with other railroads. In New York, this meant connecting to the new IRT and New York Central Railroad depot at 42nd St.

The H&M proposed two extensions of their Uptown Tubes. The first would be a short branch along 9th St, where the existing tubes curve under 6th Ave. The 9th St branch would extend to 4th Ave where a station would provide a transfer to the IRT at Astor Place. About 250 feet of this branch was built, and the provisions can clearly be seen while riding trains between 14th St and 9th St stations.

The 9th St branch was always an odd idea, as H&M riders could easily transfer to the IRT in Lower Manhattan (the Hudson Terminal being one block from the Fulton St IRT station. Even more puzzling was the at-grade junction that was built, considering the more complex and expensive flying junctions built in New Jersey. Likely, the 9th St branch was never really going to be built, but would have been a bargaining chip used by the railroad for future concessions on new lines.

The Uptown Tubes had not yet opened past 19th St when the extension north to 42nd St and Park Ave to the new Grand Central Terminal was proposed. This delayed the opening of the 23rd St, 28th St, and 33rd St stations. The plans called for additional stops at 38th St/6th Ave, 5th Ave/42nd St, and Grand Central (42nd St/Park Ave).

At this time, the IRT had been given the rights to the Steinway Tubes (which today carry the 7 train), a pair of trolley tunnels between Manhattan and Queens once designed to carry the LIRR to the new Grand Central Terminal. However, the tunnels were not put into service until 1913. The Steinway Tubes terminated at a large station deep below the IRT and Grand Central. When the lines were under construction, space was left between the deep terminal and the more shallow IRT station for the H&M.

McAdoo proposed extending the Downtown Tubes north, parallel to Broadway to Union Sq, then along Broadway to Herald Sq, and up to Grand Central. This would have united both branches. He also proposed taking over the Steinway Tubes for through service between New Jersey and Long Island.

McAdoo claimed that his company was planning on beginning construction soon, but each year would delay the project with the Public Service Commission, the state commission set up to plan and manage new subway lines. When the IRT began work on their Lexington Ave Line, which branched off of the original IRT tunnels at Grand Central, they intentionally dug utility shafts straight through the area left for the H&M, supposedly blocking the space for future use. Eventually, the Public Service Commission got fed up with McAdoo’s delays, and after the 17th request for delay, the Commission denied his request, effectively ending the H&M’s legal rights for building an extension.

While digging the IND 6th Ave Line in the 1930s, the city began negotiations with the H&M to take over the Uptown Tubes. The H&M had been built directly down the center of 6th Ave, and the IND wanted to reuse their tunnels for the express tracks of the new subway. The H&M rejected the offer, and the IND chose to build only the local tracks around the Uptown Tubes, leaving the express tracks unbuilt until the 1960s, when they would be built directly below the H&M tubes.

More importantly, building the IND 6th Ave Line required that the 33rd St terminal for the H&M be moved one block south. The 28th St station was closed, as it was deemed too close to the new terminal. The new 33rd St station was integrated into the larger BMT and IND mezzanine under Herald Sq. This mezzanine, as well as a now closed pedestrian passageway between 34th St and 42nd St, blocks any further extension of the PATH.

IRT connections and the Triboro Plan

The IRT and H&M were both private companies, but with different philosophies about customer service. The H&M’s de facto slogan was “The Public be Pleased”, the opposite of the prevailing attitude towards railroad customers encapsulated by William Henry Vanderbilt’s “the public be dammed!” quote. While the IRT had proved popular at first, their poor service, crowded trains, and dirty stations quickly soured the city’s attitude toward the company. As such, the Mayor proposed that new lines be built by the city, keeping the IRT locked out of new lines.

Early plans for this new system, dubbed the Triboro Plan, called for a new subway along Broadway and Lexington Aves into the Bronx, and subways along 4th Ave and Lafayette Ave in Brooklyn. McAdoo proposed that the H&M operate these lines, but not build them. His plan also called for the H&M to connect directly to the IRT at Broadway, running north to 10th St and looping back into New Jersey. Additionally, he called for the Uptown Tubes to be connected directly to the Steinway Tubes at 42nd St.

Even in its day, the H&M was seen as an outsider; a New Jersey railroad trying to muscle its way into New York City transit. McAdoo’s overtures to the city faced a cool reception, but more so because he expected the city to pay for the construction itself. The IRT saw this as competition to their subway monopoly, and fought to improve their image so that they would get rights to the new lines. Ultimately, it was a company from Brooklyn which won the rights to many of the new lines instead, meaning that the new expansion plans would be split between the IRT and BRT under the Dual Contracts, and not the Tri-Contracts as may have been the case if the H&M were involved.

Other New Jersey Connections

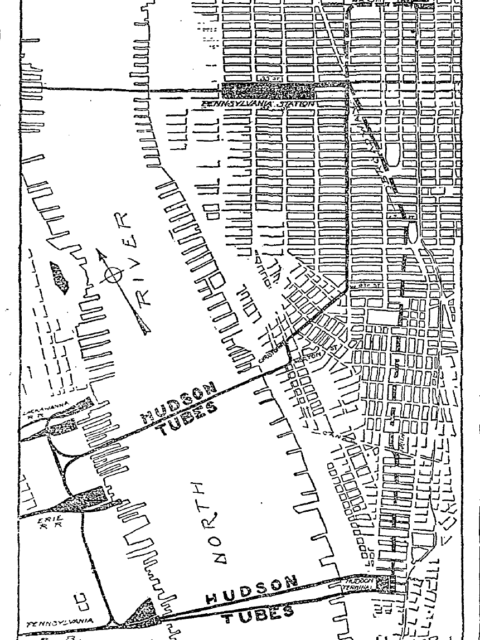

When it opened, the H&M connected three of the largest railroad terminals on the New Jersey waterfront to New York. But it didn’t connect all of them. The major omission was the Central Railroad of New Jersey (CNJ) terminal in Communipaw. The CNJ terminal was built south of the main body of Jersey City, cut off by the Morris Canal basin. While the terminal sits directly across from the southern tip of Manhattan, it was likely left out of H&M plans because of high real estate costs on the Manhattan side led the location of the Hudson Terminal to be located too far to the north.

To remedy this, the H&M built a flying junction near Exchange Place with provisions for a tunnel going directly south to the CNJ terminal. When the Grove St station to the west of the junction was opened, bell mouth provisions were built to the west of the station for an alternative connection, either to the CNJ terminal, or for a direct connection to their tracks down to Bayonne, NJ.

To the north, similar provisions were built into the large flying junction with the Uptown Tubes. While the Hoboken and Exchange Place stations had been built adjacent to the Delaware & Lackawanna RR and Pennsylvania RR terminals, respectively, the Pavonia station (today, Newport) was built about 1,200 feet west of the Erie Railroad terminal. Initially, a short tunnel was built for a future line directly to the terminal. This was soon abandoned, and a long pedestrian passageway was built instead.

Plans for a third set of Hudson River tunnels were designed to connect Hudson Terminal to the Erie Terminal, and either connect with the flying junction, or continue west to Hoboken along the Pennsylvania RR embankment, which today sits abandoned bisecting Jersey City. Additional provisions were build into the flying junction that would have connected this embankment directly to the Uptown Tubes.

A final proposal from McAdoo was to extend the H&M deeper into New Jersey. When the H&M still terminated at Park Row in Newark, McAdoo proposed that it be extended westward, with a branch to South Orange, NJ and a branch to Montclair, NJ. Likely, this proposal was to serve real estate development in these more well-to-do suburbs for Wall St bankers that would get a one-seat-ride into New York. It may have also been a threat to the Delaware & Lackawanna and Erie Railroads, which ran through these towns, so that they would play nice with the H&M.

Ironically, while the Pennsylvania and Erie RR terminals were both demolished, the terimal building for the CNJ still stits, now disused, in Liberty State Park overlooking Lower Manhattan and the Statue of Liberty.

Interstate Loop

In response to the massive growth in population and industry after World War 1, New Jersey began looking at ways to deal with trans-Hudson traffic. Ridership on the three railroad crossings (H&M and Penn Station) were maxed out. The other railroads that hadn’t built tunnels of their own and still relied on ferries to move the thousands of daily commuters across the river.

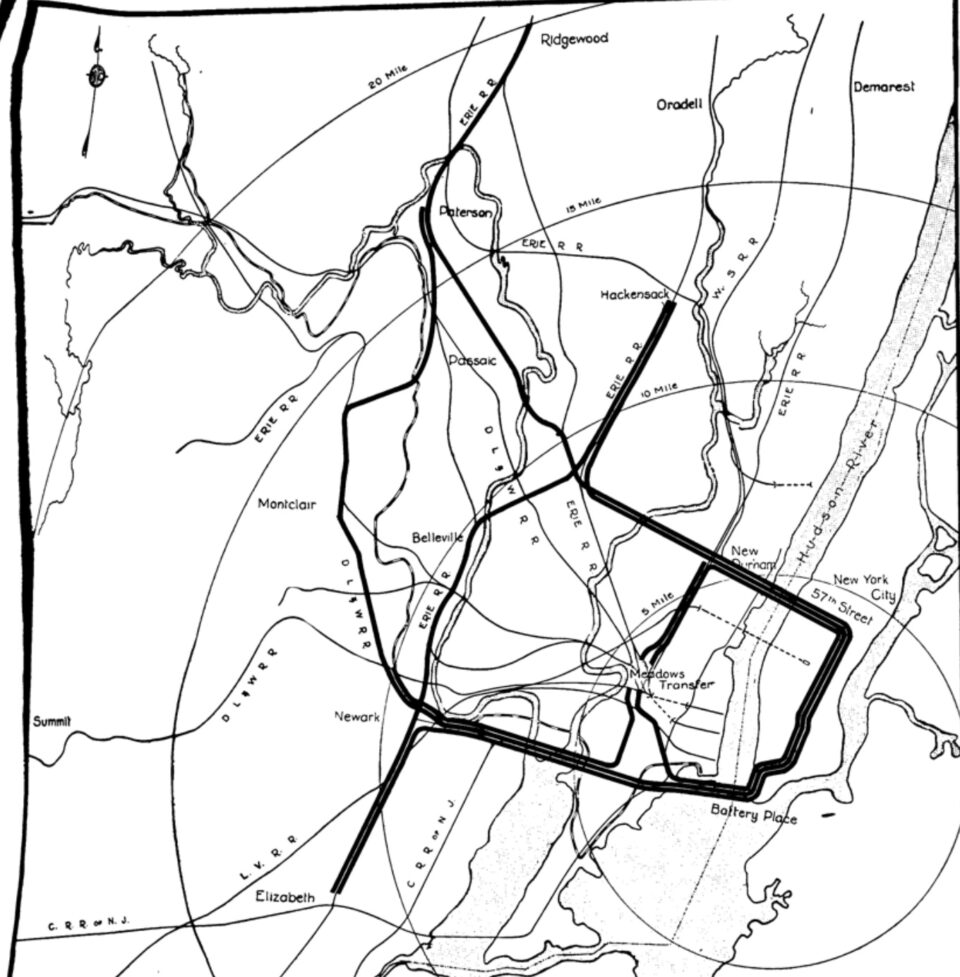

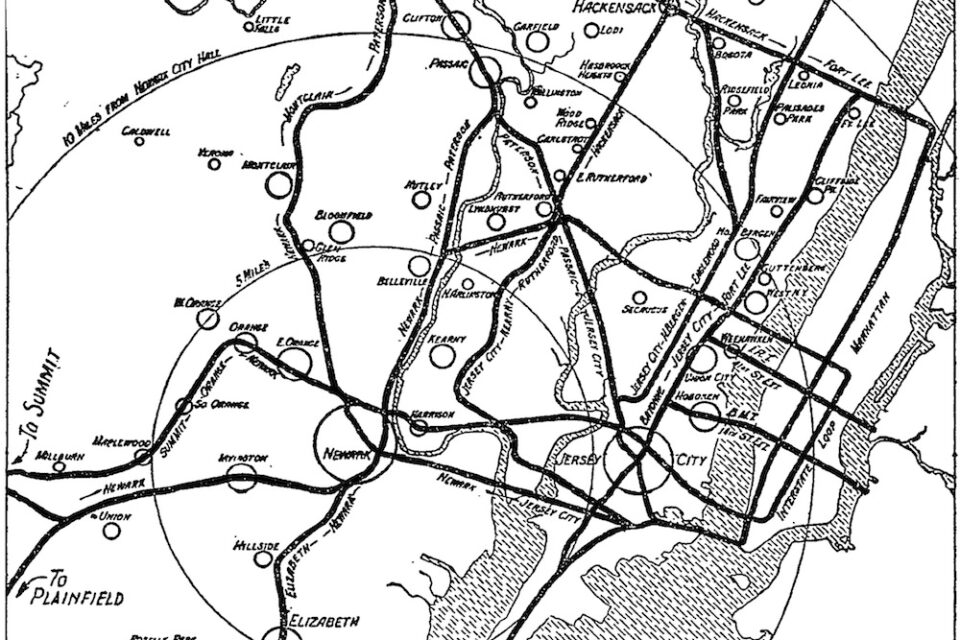

In 1926, the North Jersey Transit Commission submitted their plans for an ambitious rail loop from New Jersey, through Manhattan, and back into New Jersey. This plan was independent of the H&M, and was envisioned to serve the existing railroads of New Jersey, pending their conversion from stream to electric power.

The loop would begin in Newark, funneling Delaware & Lackawanna and Erie Railroad lines along the CNJ across the Hackensack River into Jersey City. From the CNJ terminal in Communipaw, the line would cross to the Battery, then under Washington and Barclay streets, Park Row, Mulberry Street, Lafayette Street, Irving Place, Lexington Avenue and 57th Street. The line would turn back to New Jersey, coming above ground at New Durham in Union City, NJ. From there, lines would extend across the Meadowlands to Rutherford, connecting to the Erie RR lines to Paterson and Hackensack.

In addition to the New York tubes, a set of loop tracks would be built between New Durham and Communipaw. These would serve the large Meadowlands Transfer station, which would have been located just north of present Journal Square. This station would have provided transfers to the West Shore Railroad, as well as the H&M, local streetcar lines, and any other railroads that were still steam operated.

The proposed extending the H&M north from the Hoboken Terminal to 14th St in Hoboken, and west from the Newark Terminal to Irvington, NJ. It also considered extending New York subways as well; the IRT was to have branches from both east side (4,5,6) and west side (1,2,3) lines to the Meadowlands Transfer, while also extending the Flushing Line (7) to Weehawken, NJ. The BMT 14th St Line (L) was to be extended across into Hoboken and south into Jersey City. Tying these lines all together was to be a subway running from Port Richmond, Staten Island, to Fort Lee, NJ, along various streets, but most notably Bergenline Ave.

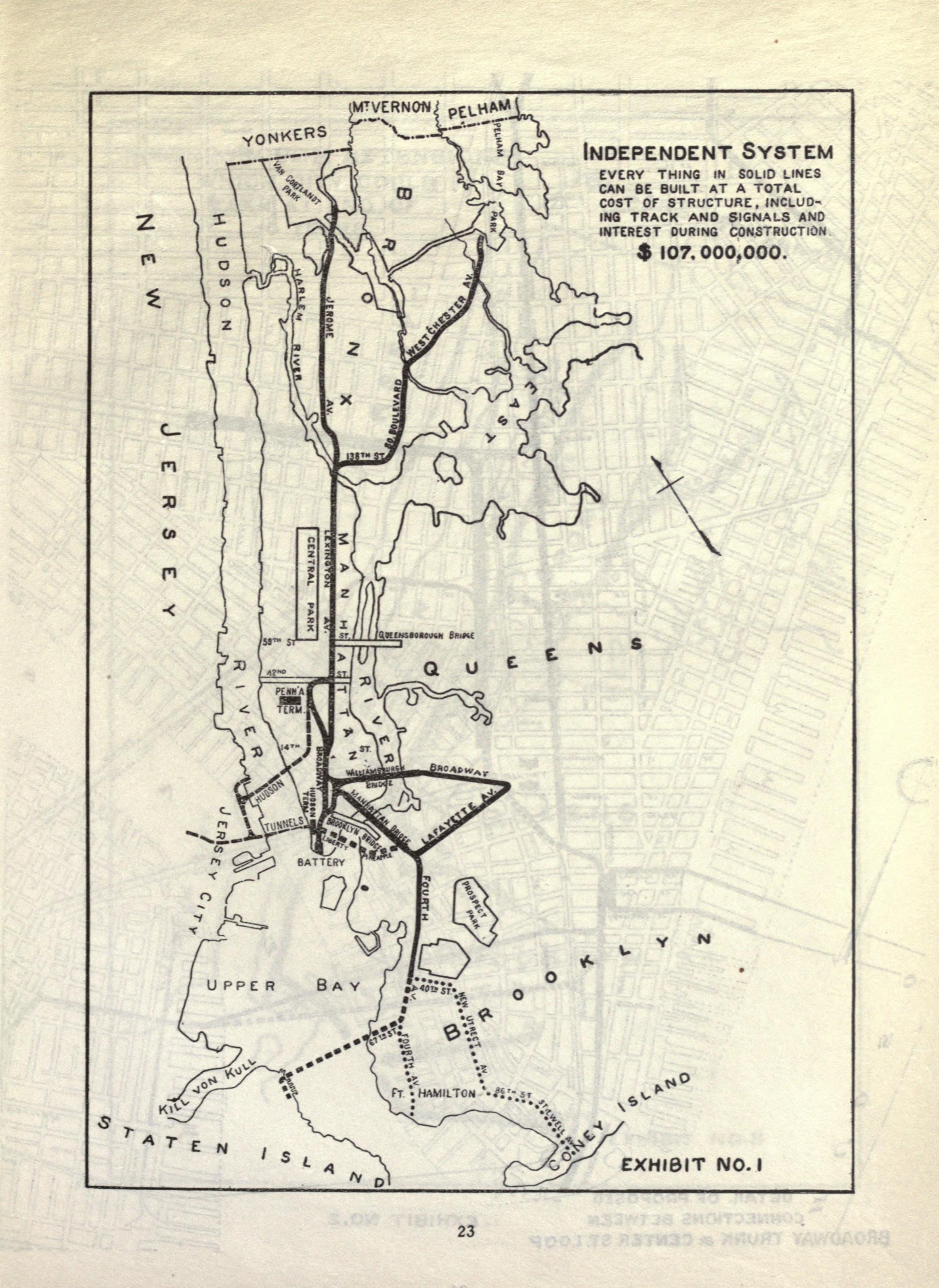

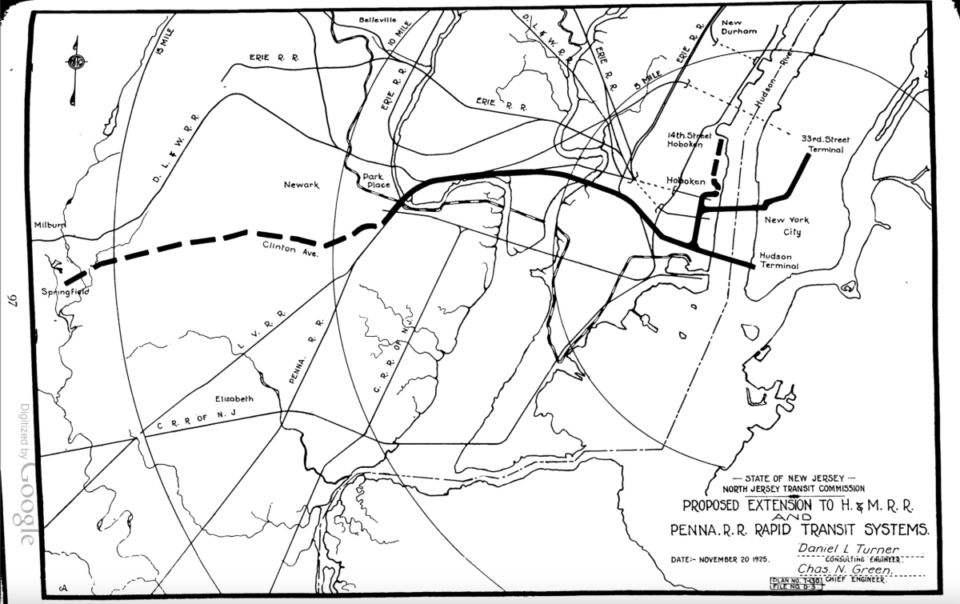

The next year, the commission updated its plans. New York City had just announced their new Independent System (IND), and the commission looked at variations of their plans to include connections to the new 8th Ave Line. The largest addition to the plans was the Westchester-New Jersey commuter subway. Very simply, this would have extended the New York Central RR from Grand Central to the Battery, then cross to Communipaw and link up with the CNJ to Newark and the Meadowlands Transfer station.

Like all great plans, this was undone by lack of money and bad timing. Even its authors understood that neither state nor private railroads had the funds to build such an audacious scheme. It was suggested that parts of the system be built first, then additional connections added later as financing became available. In later 1929, the stock market crashed, erasing all potential options for financing, and relegating the Interstate Loop plans to the trash heap of history.

Decline

McAdoo left the H&M in 1913 to become the Secretary of the Treasury under President Woodrow Wilson (he also married Wilson’s daughter). The H&M wasn’t interested in expanding as it held a virtual monopoly on cross-Hudson traffic, and split revenue with the Pennsylvania RR for transfers at Exchange Place and Manhattan Transfer stations. 1927 saw the highest ridership on the H&M (113 million riders). But that year, the Holland Tunnel opened, allowing motorists a direct route from anywhere in NJ into New York City. This immediately hit the H&M as ridership began to tumble. That year, the H&M was rerouted from its Park Row terminal to the new Newark Penn Station, owned by the Pennsylvania RR. Later, the opening of the George Washington Bridge and Lincoln Tunnels added to H&M losses.

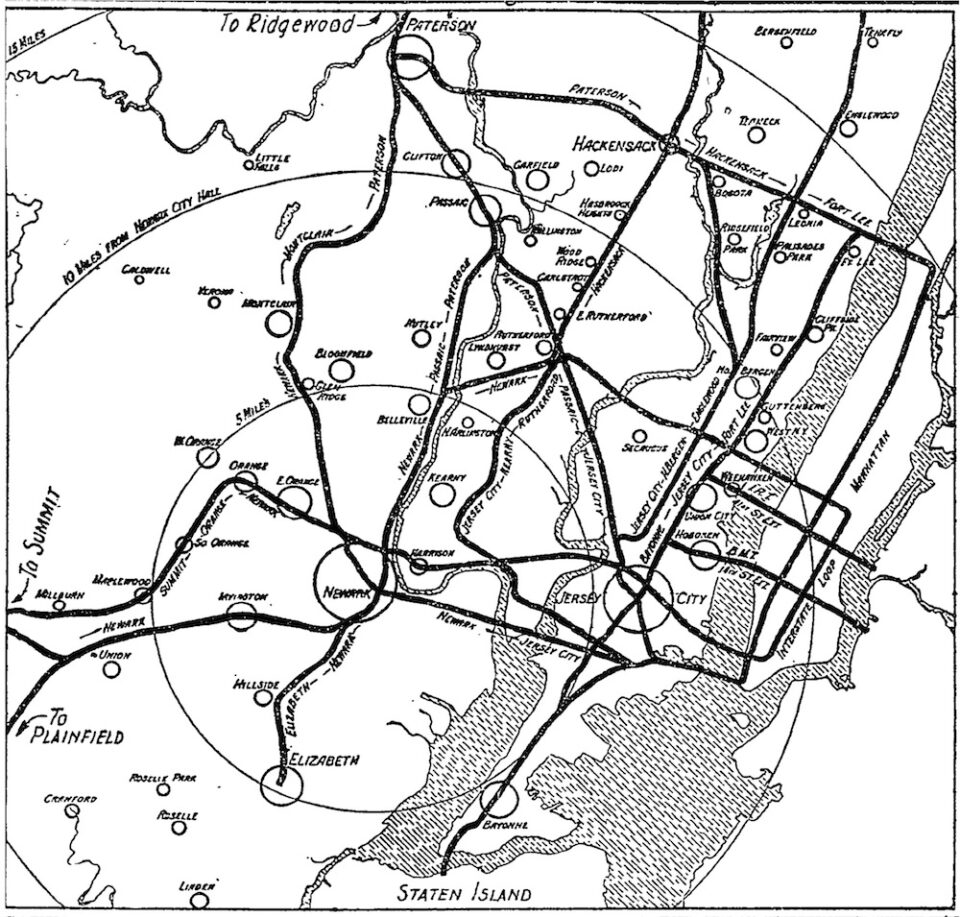

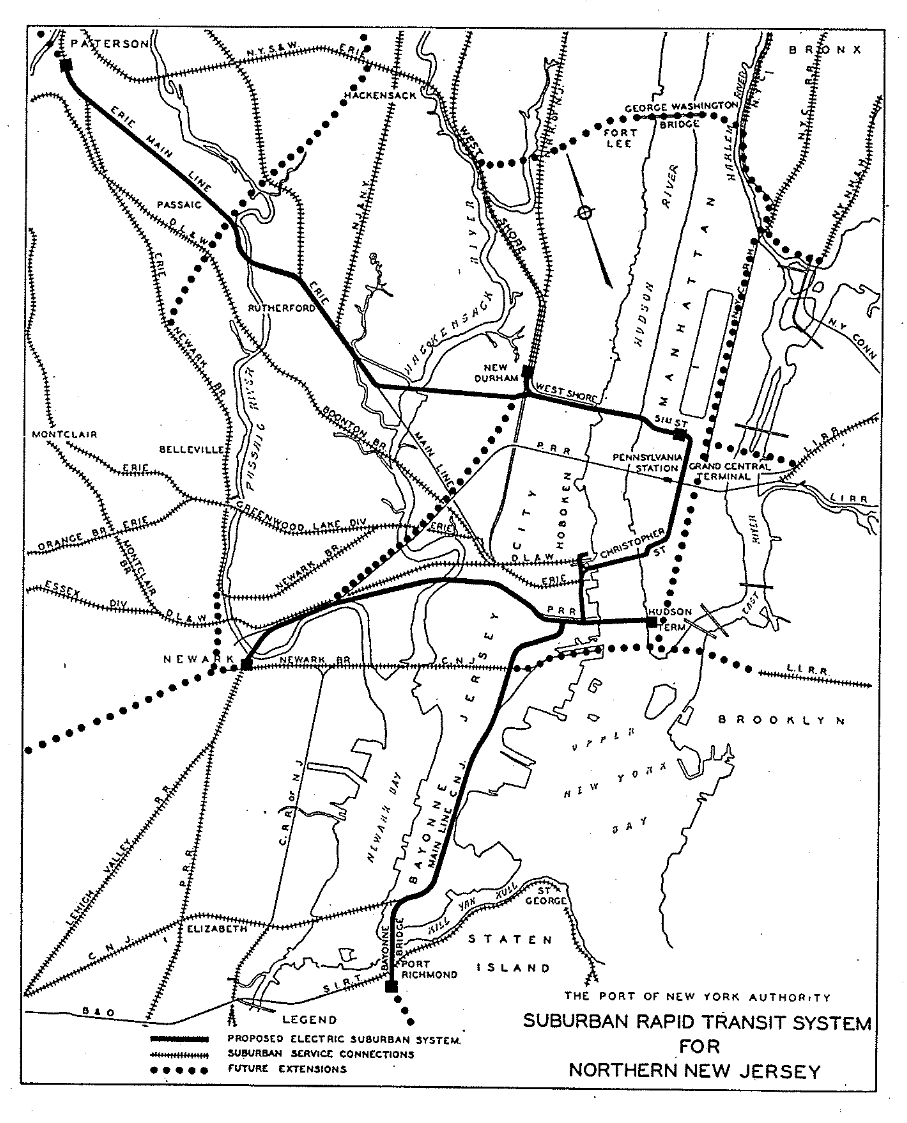

In 1937, the Port Authority was asked to look at mass transit options for areas west of the Hudson River. Their initial plan copied much from the North Jersey Commission plans, but distilled the new lines into an expansion of the H&M.

Their initial plan called for expanding the H&M up 6th Ave to 51st St (with a station at the new Rockefeller Center), then crossing back into New Jersey parallel to the West Shore RR tunnel under Union City, NJ. A transfer station would be provided to the West Shore RR at New Durham (roughly where the Tonnelle Ave Hudson-Bergen Light Rail station is today), and a branch across the Meadowlands to East Rutherford. This branch would run along the Erie RR to Paterson. In the south, a new branch would be built along the CNJ through Bayonne, from Grove St station, across the Bayonne Bridge, and terminating at Port Richmond, Staten Island. The plan called for other new lines in the future.

While this plan worked well on paper, the unfortunate truth was that the Port Authority was legally prevented from operating a money-losing commuter rail system as part of its original charter. The H&M was in no position to build such a network, and the railroad companies were cool to the idea (especially if no one was willing to buy).

In 1940, after years of diminishing returns, poor service, and dirty trains, the IRT and BMT (which had replaced the bankrupt BRT) called it quits, and were bought by the city in what was known as unification of the subways. The H&M was not part of this transaction. The smaller system was able to survive as it was cheaper to operate, and crossings between New Jersey and New York were still limited. However, after World War 2, the tide fully changed. New state and federally funded highways began to connect the suburbs and hinterlands of New Jersey, with the bridges and tunnels between the two states. More than ever, riders were flocking to cars. It wasn’t just the H&M that began to suffer.

Many of the large railroads that served the mid-Atlantic states began to hemorrhage money. Bound by archaic laws that prevented them from abandoning money-losing lines, ballooning labor costs, and dwindling ridership, urban planners began to look at ways to shift passenger service away from the railroads and into mass transit. Commuter lines that could still attract riders could be connected to existing subways. In 1954, the H&M fell into receivership, and would struggle as ridership continued to drop.

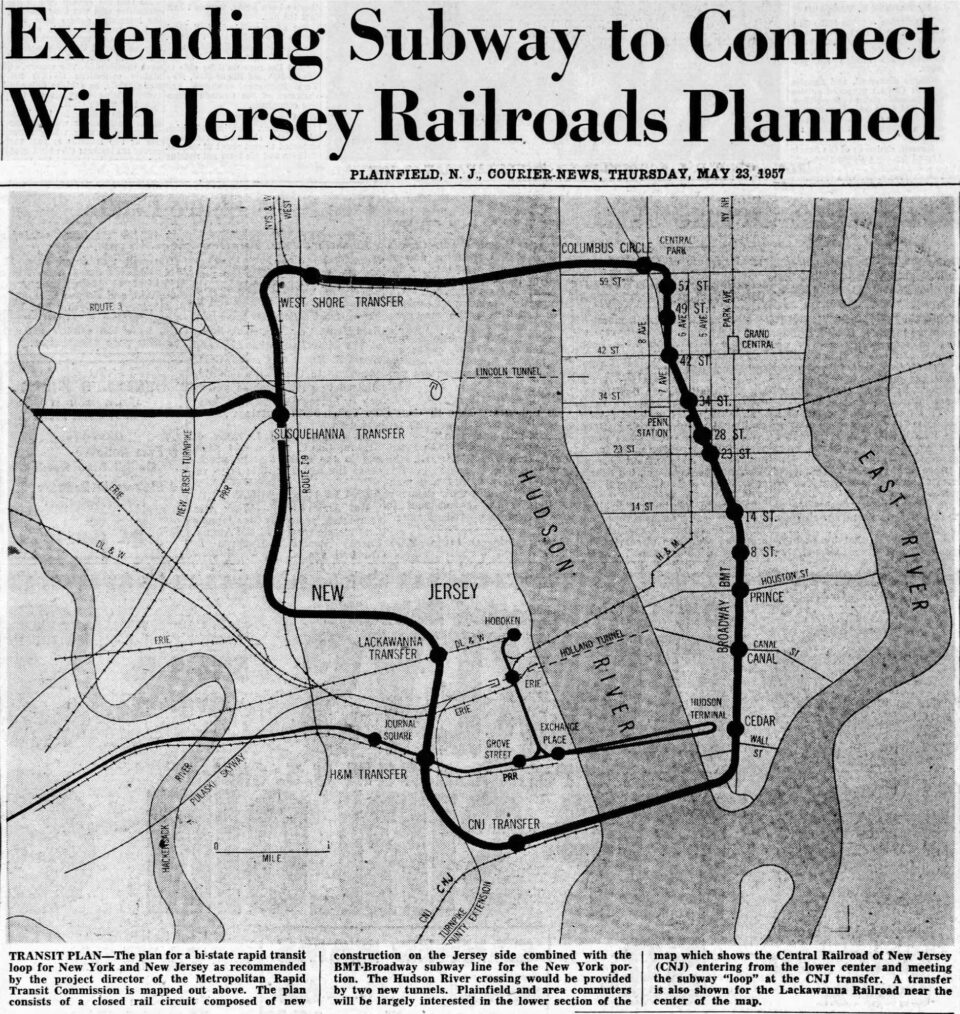

In 1957, a final loop plan was proposed by the Metropolitan Rapid Transit Commission. This plan was similar to the Meadowlands Transfer proposal, but instead of building a new tunnel though Manhattan, the commission proposed using the local tracks of the BMT Broadway Line from Lower Manhattan to 57th St. This plan would have been separate from the H&M, as BMT trains were wider than H&M tunnels could accomodate.

The connections in New Jersey would be the same, with a transfer at New Durham and Communipaw, but also a transfer to the H&M south of Journal Sq, and a transfer to the Lackawanna west of Hoboken. The loop also featured a branch to the Erie RR in Rutherford. While this plan saved money by using the existing New York subway (NYCT), it also required a city-run authority to have jurisdiction over a railroad in New Jersey. Given that NYCT was facing declining ridership and revenue as well, it’s understandable that the plan went nowhere.

Port Authority Take Over

The post-War years brought a massive real estate boom to Midtown Manhattan, which offered more land for larger offices than the cramped, colonial streets of the Financial District. As firms moved uptown, real estate prices in Lower Manhattan plummeted. Concerned, Governor Nelson Rockefeller, whose family owned the Chase Bank located in Lower Manhattan, proposed an ambitious plan to redevelop Lower Manhattan. The first step would be to consolidate international trade operations into a brand-new office complex, a World Trade Center.

Initially, a site was chosen along the East River. But Rockefeller found few firms interested in building and operating such a facility. Rockefeller looked to the Port Authority, which had a surplus of funds from their bridges, tunnels, and airports. Given that the Port Authority was a bi-state agency, New Jersey needed to sign off on the project. To entice New Jersey to sign on, it was proposed that the Port Authority buy the H&M. As part of this deal, the Port Authority would also be buying the Hudson Terminal, located on the west side of the Financial District. This moved the location of the WTC, which would now be built directly above the old terminal.

The Port Authority would take over the H&M in 1962. As they were legally barred from operating mass transit facilities, they created a subsidiary corporation, the Port Authority Trans-Hudson (PATH) Corp. to run the railroad. This further shielded the Port Authority from Interstate Commerce Commission rules. PATH set about modernizing the system, including creating a new livery design for the trains and stations.

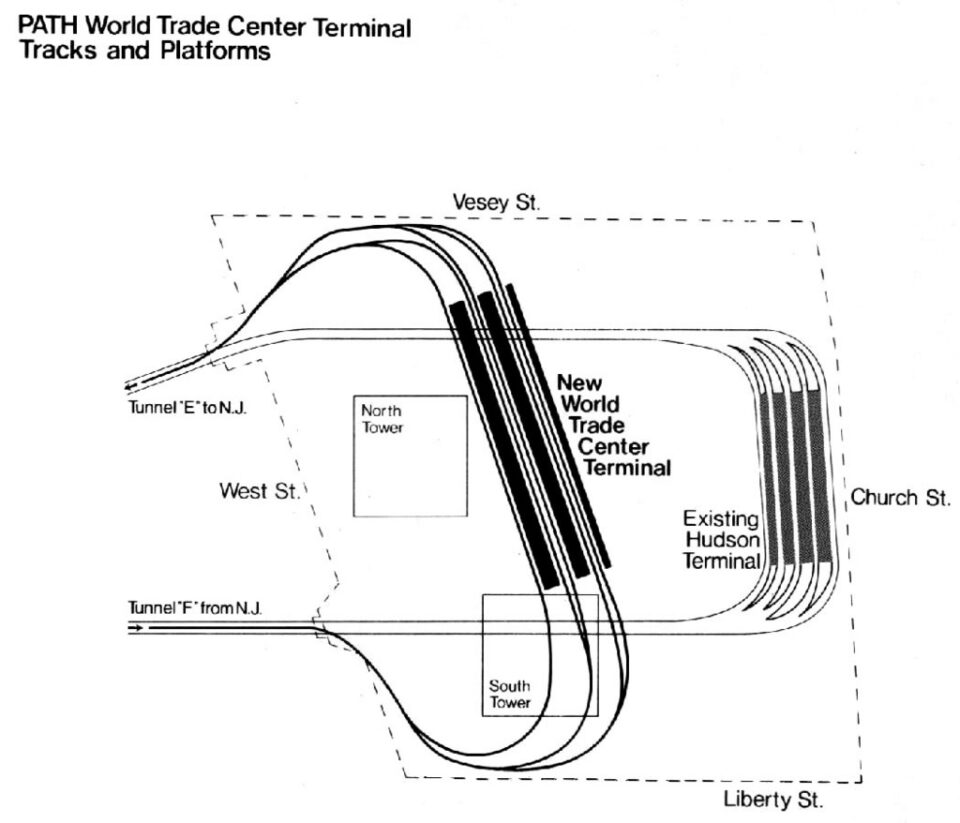

PATH operated while the WTC was under construction. The new terminal would be larger than the old Hudson Terminal, but moved one block to the west. At the same time, PATH also built a new transportation center at Journal Sq, with better bus facilities and parking.

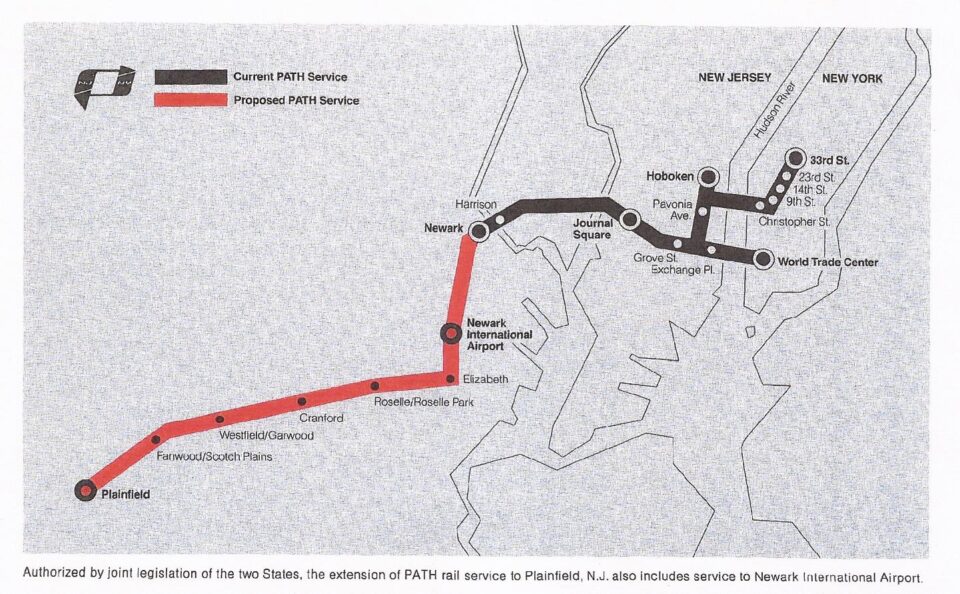

To capitalize on their “new” system, PATH proposed an extension from Newark to Plainfield, NJ, along the defunct CNJ Main Line. This would include a stop in North Elizabeth, where a station along the Northeast Corridor (NEC) would be built for a connection to Newark International Airport (now Liberty). Elizabeth was the next major city south of Newark, and the line out to Plainfield had been built up as a commuter suburb.

PATH’s plan was not cheap, coming in at about $400 million ($2.3 billion in 2024). They expected the Federal Mass Transit Administration to cover 80% of the costs. The Feds balked at the cost, asking NJ and PATH why a more affordable passenger service on the old rails couldn’t be run instead? At the same time, there were questions about the basic legality of PATH service in the first place. In 1977, the US Supreme Court ruled that PATH had violated their 1962 bond agreements by repealing a covenant that stated that the Port Authority could not finance any commuter rail projects that would lose money. Now that the state alone would have to finance the project, New Jersey opted for limited commuter rail and bus service at a much lower cost.

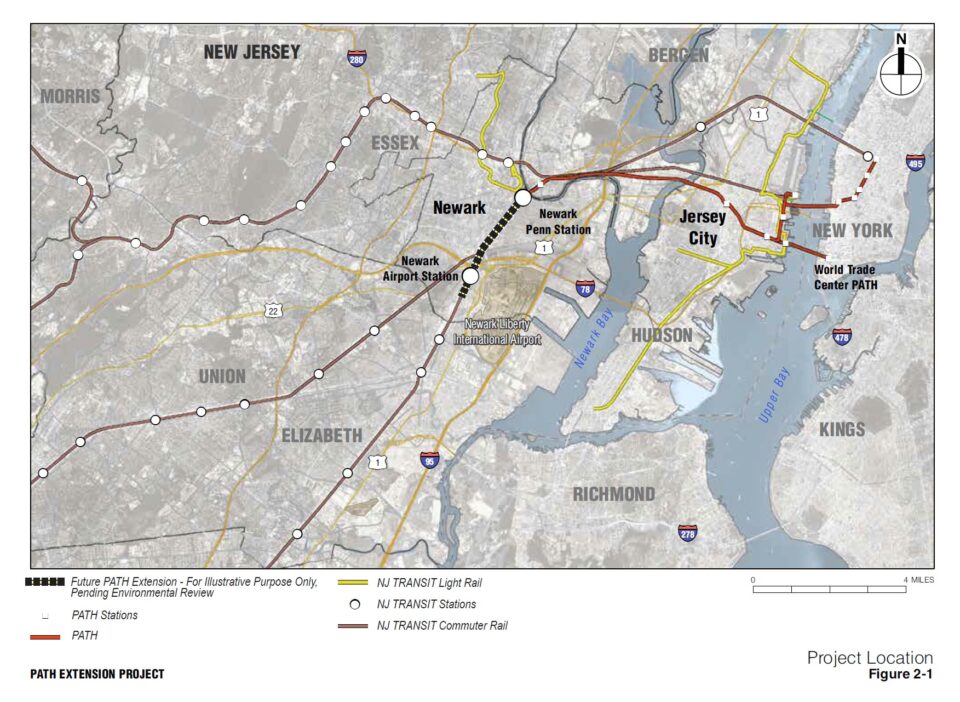

PATH has held out hope for an extension to Newark Airport, or at least, a station along the NEC with a connection to the airport people mover. While on the map it appears that PATH ends at Newark Penn Station, in reality the tracks continue southeast along the NEC almost a mile to South St. It’s only 1.6 miles south to the Newark Airport station as it is. The idea of extending PATH gained new traction after 9/11, as the Port Authority began to work closely with New Jersey and New York states on rebuilding Lower Manhattan. A direct link to the airport was seen as a way to bring travelers and business back.

Like all low-hanging fruit, this too has withered on the vine as the cost of rebuilding the WTC ballooned, and all parties involved bickered over who got credit. The new train terminal building at WTC, initially supposed to cost $1 billion, ended up costing 4 times that. The Port Authority was also looking at the costs of replacing their now ancient bridges in Staten Island. All along, the cost of the 1.6-mile extension has grown as well. More important projects always seemed to be in the way. Not to mention, Newark Airport is served by Amtrak and New Jersey Transit already, so it’s not exactly limited.

The Newark Airport extension has also faced pushback from New Jersey lawmakers, who want the line to include a station in the South Ironbound neighborhood. The NEC once had a station at South St, where the existing PATH tracks end. It’s possible that PATH did not include a station here in an attempt to skim around the commuter rail issue, as well as attract Federal funds for airport connections which, before the Biden administration, prohibited stations not directly related to airport facilities.

The Newark extension is still in the most recent Port Authority Capital Plan, though most of the money allotted to the project is for design only. It’s possible that more money will be provided in the next plan, but when push comes to shove, PATH will always be the red-headed stepchild of the Port Authority family.

PATH-Lex

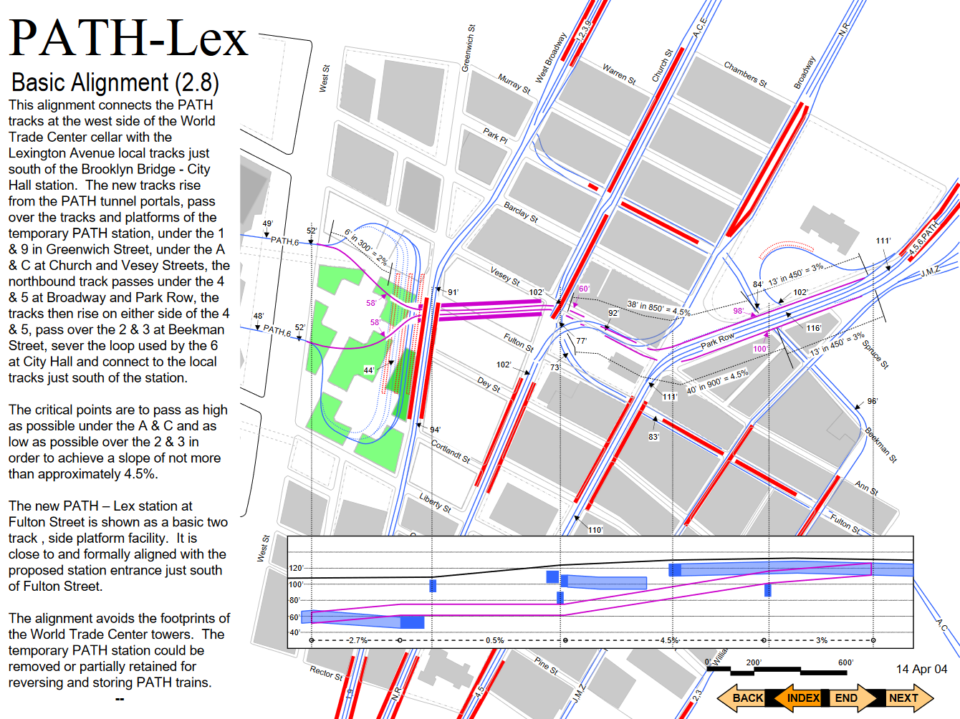

While this last proposal was never official, I’d be remiss to not include it as it seems to still be kicking around in the minds of railfans. A direct connection between PATH and the IRT Lexington Ave Line was first proposed by William McAdoo, but it’s questionable how serious he was about it. This new iteration was proposed by the now defunct Regional Rail Working Group, and its Chair, George Haikalis.

The proposal was floated after 9/11, when there was, unfortunately, a clean slate so-to-speak around the WTC. The idea was simple: instead of building a new, and expensive, terminal, the two Downtown Tubes would instead be extended under the former WTC to Vessy St (with a new WTC station below), then under existing subway tunnels to link up with the local tracks of the Lexington Ave Line. In essence, the PATH would merge with the 6 train. This works because both systems have similar sized trains.

It’s questionable if the plan was really feasible. The new tunnels would have been just as complex to route under the congested streets. Both the WTC Occulus and Fulton Center projects went greatly over budget, and this would have likely done the same. There is also no discussion of the fact that PATH trains are shorter than NYCT A Division (number lines) trains, or that the PATH runs with a slightly different voltage than NYCT. It’s possible that the idea was to also upgrade the entire PATH, but this would then negate any cost savings. Regardless, the plan went nowhere and is likely impossible today.

Conclusion

In 2023, PATH moved over 55 million riders between New York and New Jersey. This alone puts it as the 5th most ridden metro system in the United States. When comparing New York City, which is relatively well covered by rail mass transit, and New Jersey, it’s easy to see why dreamers have time and time again proposed new lines on the west side of the Hudson. There is little technical reason that new lines can’t be built. It has always been, and will always be, political. New Jersey Transit was founded in 1979 to run the defunct commuter rail and bus operations. But NJT doesn’t own any of the crossings it uses to bring riders in and out of New York.

The Port Authority doesn’t see this as an issue, since they get a cut. NJT, like the MTA, is perpetually underfunded and poorly run, making it hard to trust them to expand service. Often, when service is expanded, it’s in the center of the state, where there are more influential politicians who can get pet projects built. A large part of the political issue is that the very cities in the northeast of the state that would benefit the most from PATH expansion are fractured and often can’t work well together. After all, the New York City subway was only possible after New York gobbled up Brooklyn (formerly an independent city), Queens and Richmond Counties.

Even something as *simple* as building a new tunnel for the NEC has taken decades longer because of political infighting. What was known as the ARC Tunnel (Access to the Regions Core) was stopped right after digging started by former NJ Governor Chris Christie. It took another decade, and a new Presidential administration, to get things moving again on a whole new plan.

Therefore, it will be up to a visionary power broker in New Jersey to figure out how to build the right tools for constructing the right kind of mass transit system that has the authority and the funding to properly expand mass transit between New York and New Jersey.

Coda

There are a few other New Jersey expansion plans that have kicked around for decades that weren’t directly related to this post, but I’m sure they will come up in the comments. So I’ll address there here.

Hudson-Bergen Light Rail: The Hudson-Bergen Light Rail (HBLR) system is one of, if not the only, flower to bear fruit from the old North Jersey plans. While the core of the system runs along city streets in Jersey City, its branches use defunct rail lines in Bayonne and Hoboken. Presently, the network ends at Tonnelle Ave. But the network was always supposed to have been extended further north to Englewood. Other alignments were proposed as well, including one branch out to Met Life Stadium and up to West Nyack. The plans have been kicked down the road so long that the Federal Transportation Administration recently sent New Jersey back to do a new Environmental Impact Statement because the original one is so out of date.

HBLR to Staten Island: Presently, the HBLR ends at 8th St in Bayonne, a stones throw away from the entrance to the Bayonne Bridge. The bridge was constructed with two unused right-of-ways for future rapid transit (the arch design was specifically chosen for this). Over the years, many have proposed extending the HBLR (or previously, PATH) over the bridge to Port Richmond in Staten Island.

There are a number of problems with such and extension. The HBLR (owned by NJT) would need the funding and desire to extend their tracks to Staten Island, which would mean they would be entering MTA territory. Most commuters from Staten Island are heading to New York (Manhattan and Brooklyn making up the majority). Despite being closer and better connected to New Jersey, the percentage of interstate commuters is low. Travel times wouldn’t be all that competative to MTA buses and the Staten Island ferry. Lastly, the Port Authority’s recent raising and rebuilding of the Bayonne Bridge has expanded the road deck and new pedestrian/bike paths over the old rapid transit right-of-way, meaning that it might not be possible (or at least affordable) to extend the HBLR over the bridge.

The MTA is moving ahead with a Bus Rapid Transit line on the abandoned SIR North Shore Branch, so it may be possible to incorporate BRT between Staten Island and Bayonne instead.

George Washington Bridge: More well known, the George Washington Bridge was built with space on the lower deck for two sets of rail tracks. I’ve seen very few realistic plans for how this would have looked, though the 1937 Port Authority proposal does include a “future” line between Hackensack and the Bronx. The IND 8th Ave Line has tracks continuing north past 168th St which would have allowed for an extension over the bridge. When the lower level was built, and connected to the Trans-Manhattan Expressway, the ramps connecting the bridge and Riverside Drive were built directly where the tracks would have gone. In effect, these ramps block any potential extension of the New York subway over the bridge, if the Port Authority would even consider the idea.

7 Train to Secaucus: Possibly the most recent, and serious (for what it’s worth) proposal was by then Mayor Michael Bloomberg to extend the 7 Train across the Hudson River to Hoboken and Secaucus. Bloomberg was championing the 7 extension to Hudson Yards at the time, and saw work on the ARC tunnel going nowhere. While detailed plans were drawn up, it’s tough to tell how serious they were given that the MTA wasn’t even a fan of extending the 7 to Hudson Yards to begin with.

Man what coulda been. NYC shoulda let the PATH have 6 Ave and built their line somewhere else or focus on building the 2 Ave line.

Hard disagree. 6th Ave runs up the center of Midtown and connects to other lines. 2nd Ave doesn’t.

Yeah but 2nd Ave would have 4 tracks and a connection to Brooklyn via Fulton St local tracks not to mention a shallower 2 Ave line that serves a currently subway-less area. We’d have a full capacity balance entirely on the East Side of Manhattan. The fact that most stations r express stops on 6 Ave makes the local/express line seem pointless despite the fact it serves so many ppl in the center of the city. It shoulda stayed two tracks. Plus with an expanded PATH, NJ residents wouldn’t have needed to heavily rely on buses going thru congested traffic from the tunnel to PABT, nor would they have to rely on cars going thru congested traffic in the Holland Tunnel. With a 2nd Ave line instead of 6 Ave, we’d have line in the Bronx serving areas without service.

Would it be possible to swap the PATH and 6 AV express tracks so that it could be extended further north under Herald Square?

No.

vanshnookenraggen – Another excellent post! A very nice summary of the various proposals through the years. Bravo! And thank you.

Your comment that “It has always been, and will always be, political.” is 100% spot-on, particularly now that we are well into the era of public ownership, operation and – most importantly – subsidy.

In my opinion, the fact that any transit extensions in New Jersey would require the Garden State to “pony up” in terms of both capital costs but also (and just as importantly) in terms of ongoing operating & maintenance costs is the key sticking point to seeing any real extensions of rapid transit service west of the Hudson.

Joseph Raskin does a fantastic job explaining this in his great book “The Routes Not Taken: A Trip Through New York City’s Unbuilt Subway System”, which I am sure you and many folks who read this wonderful blog have already devoured. You reinforce the point when stating how Governor Byrne killed the Plainfield extension: “Now that the state alone would have to finance the project, New Jersey opted for limited commuter rail and bus service at a much lower cost.”

(FYI – Another great book that delves into rapid transit planning at a metropolitan scale is “Grand Central’s Engineer: William J. Wilgus and the Planning of Modern Manhattan” by Kurt C. Schlichting – another “must read” for the New York transit history enthusiast.)

The “bottom line” – in terms of not only finances and subsidies, but also in terms of tax levies and all the other elements associated with “politics” – is that New Jersey simply doesn’t apparently (thus far, anyway) wish to pay as much as New York does for transit. It prides itself on generally/relatively lower taxes, and using these as a selling point (along with direct subsidies) to “lure” companies, people and other economic activities (cough – sports teams, movie studios – cough) across the Hudson (and Delaware, for that matter).

In my opinion, a true “metropolitan” transit system will remain out of reach as long as New Jersey and New York (and Connecticut, for that matter) have such differing philosophies towards taxing themselves to support transit subsidies. A look at the sheer number of dedicated taxes that are levied to support the MTA (ranging from the mortgage recording tax to a surcharge on every taxicab and TNC/Uber/Lyft ride in New York) would make most policy and decision makers in the neighboring states scream bloody murder and would likely never pass muster in Trenton or Hartford.

Until and unless we develop an equitable funding mechanism that supports transit at a regional scale, with proportionally equal levels of “skin in the game” in terms of subsidies from each state, then our dreams of regional transit systems will remain just that: dreams of trans-Hudson subways and through-running Regional Rails that no one can figure out how to pay for. Until then, a New Yorker who pays all the taxes associated with the MTA can legitimately ask themselves why they should pay for rapid transit in New Jersey when there are still needs east of the Hudson and Staten Island is yet to see a direct subway connection.

Thanks again!

Very interesting article. No doubt that many who follow New York transit issues don’t think so much about these trans Hudson considerations. It is fascinating to look at the machinations that have taken place over the years to prevent any real integration of service across the Hudson. The statement at the end, that it will take a visionary power broker in New Jersey is unquestionably true, but the use of that term always brings back thoughts of Robert Moses. He was unquestionably accurately identified as a power broker, but often to the detriment of better transit.

Not eactly on topic, but I’d propose a new PATH station at the intersection Brunswick Street and Christopher Columbus Boulevard in Jersey City to serve the recent and future development in that area and the western end of downtown. Also, Ferris High School would probably be a moderate traffic generator. Thoughts?