In the annals of NYC subway history there are numerous examples of grand plans which fell flat, proposed lines that were never built or started and abandoned. Until 2017, the 2nd Ave Subway was one of these lines. The current version of the line dates from the 1968 Plan for Action, proposed by the newly created MTA. In that plan, the MTA proposed two new trunk subways for the city: the 2nd Ave Subway and the 63rd St-Super-express-Southeast Line. While 2nd Ave has had a more storied past, the 63rd St Line is often forgotten. Ironic, since it was the only part of the ambitious Plan for Action which actually opened.

This statement should come with the caveat that only part of the line opened. The ambitious plan once included a second set of tracks parallel the LIRR Main Line and three subway branches deeper into Queens. As costs mounted and delays added up, these branches were pruned back. Finally, the city threw out everything but the two core sections of the line, as construction had already advanced. Even 2nd Ave was cut in favor of the Queens line.

We have forgotten these grand ambitions today, left with the scraps we could afford to build. It took 20 years to open a few miles of tunnels and another 20 to make them useful. It’s no wonder then that we have forgotten what was promised. Ironically, now that the hardest parts are finished, a new generation can begin to think about how to finish building this line as it was originally envisioned.

Background

Early subway plans for Queens were much less involved than those for Manhattan, Brooklyn and the Bronx. Queens was still mostly farmland at the turn of the 20th Century, but was seen as the next logical step for urban expansion; subways were the tools for this expansion. But due to the lack of existing development, early subway proposals were far less ambitious than those for the other boroughs.

Part of the problem of building new lines into Queens was the lack of existing capacity in Manhattan. In southern Queens, the BRT (predecessor to the BMT) was able to extend the Myrtle Line (M), Jamaica Line (J/Z) and the Liberty Ave Line (A). But in the north, the city had to contend with the IRT which had built out the first subway in Manhattan. Queens didn’t have its own transit company and both were vying for control.

The agreement between the IRT, BRT and the city was the Dual Contracts and laid out which company would build and run each new line. In northern Queens, the two new lines were to be controlled by BOTH companies. The elevated Astoria Line and Corona Line (before it was extended to Flushing) were built to support the smaller elevated trains of the IRT. The Queensoboro Plaza station was built with four platforms, two for the IRT and two for the BRT. IRT riders would have through service to 42nd St and 2nd Ave but BRT riders would have to transfer at their separate platform to subway cars to Broadway.

This new service brought fast growth to Queens. Planners quickly saw the existing lines as insufficient and began drafting new lines to support the continued growth. Even though the Astoria and Flushing Lines were designed to be extended, the East River crossings were the choke point. That meant that new tunnels into Manhattan were needed.

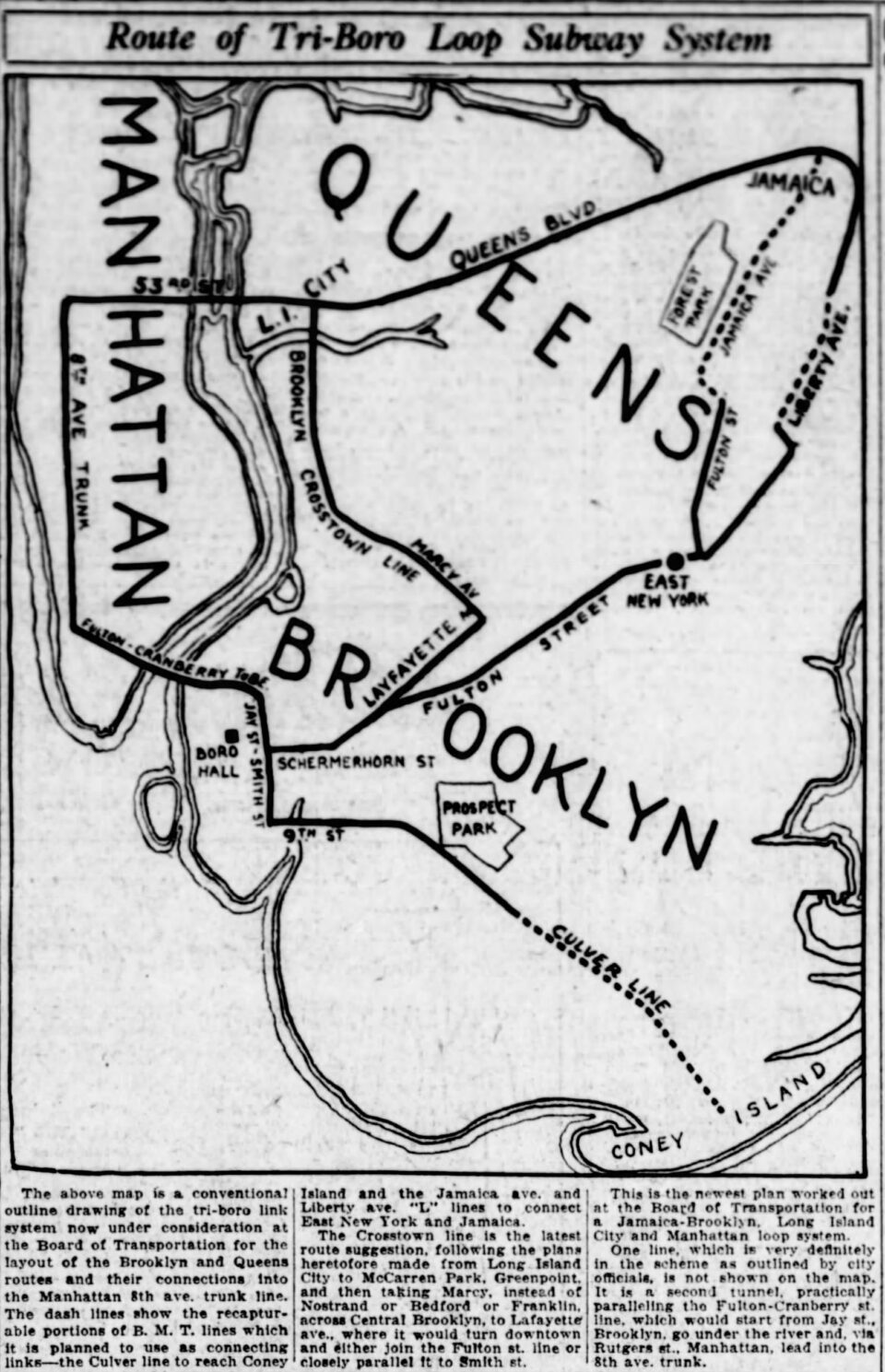

In 1924 the city took over subway expansion from the private companies with the creation of the Independent System (IND). The new IND system was building out a network of new trunk lines focused on 6th and 8th Aves in Manhattan and the Crosstown Line in Brooklyn. The original plan was to create a giant loop subway running through Manhattan, Brooklyn and Jamaica. As these plans evolved, the giant loop was dropped in favor of a more standard hub-and-spoke design with local trains serving their respective boroughs and express trains running through to Manhattan.

In Queens, the IND focused all of their efforts on a new trunk line subway along Queens Blvd. Queens Blvd had been first laid out as part of the Flushing Line, but now the city was using the subway construction to extend the road all the way to Jamaica. What is today Queens Blvd was once a series of small local streets which were combined and expanded (the city also did this with 6th Ave South and Houston St in Manhattan.)

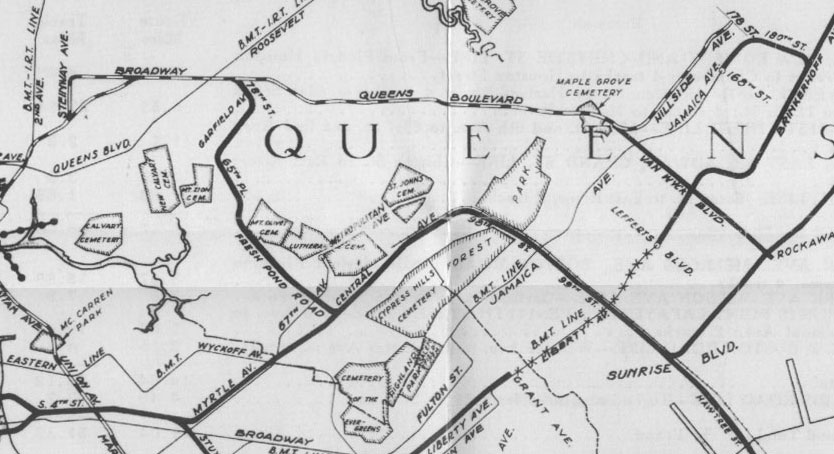

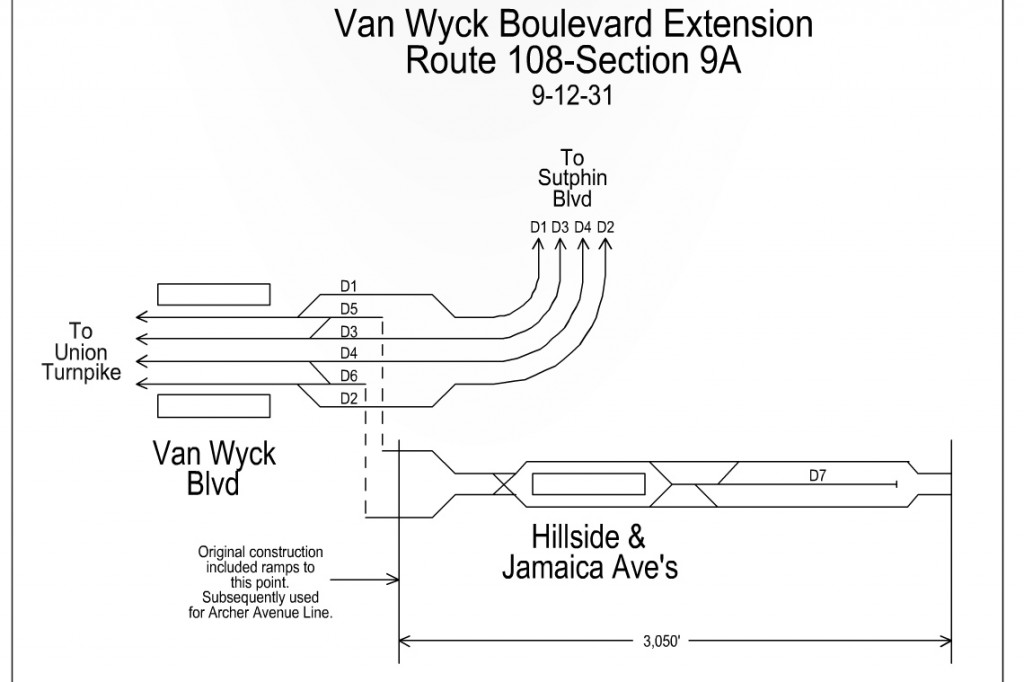

Being the core trunk line in Queens, the IND planned a number of branches and extensions of the Queens Blvd Line (QBL). I’ve covered these in a previous post, but the key provision was for a subway branch down Van Wyck Blvd in Jamaica. This was the first subway proposal for southeastern Queens. An additional extension of the elevated Liberty Ave line was proposed, snaking its way through southern Jamaica with a branch to Jamaica Ave and to Hollis.

In central and southern Queens, a second trunk line was proposed as part of the massive South 4th St Line. A branch of the 8th Ave Line was to turn down Worth St in Lower Manhattan and make its way to Williamsburg and continuing to Myrtle Ave. The Myrtle-Rockaway Line was to replace the old Myrtle Ave El and continue out to Glendale until it connected to the LIRR Rockaway Beach Branch. The line would have run south along the branch until Sunrise Blvd (today the Belt Parkway) where a branch would turn east along 120th Ave, while another would head to the Rockaways.

This second trunk would have also had connections to the Crosstown Line via an extension down Lafayette Ave and supposedly had a connection to the QBL via a line known as the Winfield Spur. Interestingly, the Winfield Spur is purported to be a fake proposal, one intended to gain political support for the overall plan. The spur is found on the 1929 IND Second System Map, yet it was the connection to the Crosstown Line which actually saw some parts built (the middle track and two layup tracks at Bedford-Nostrand station), yet this connection was not added to the 1929 map.

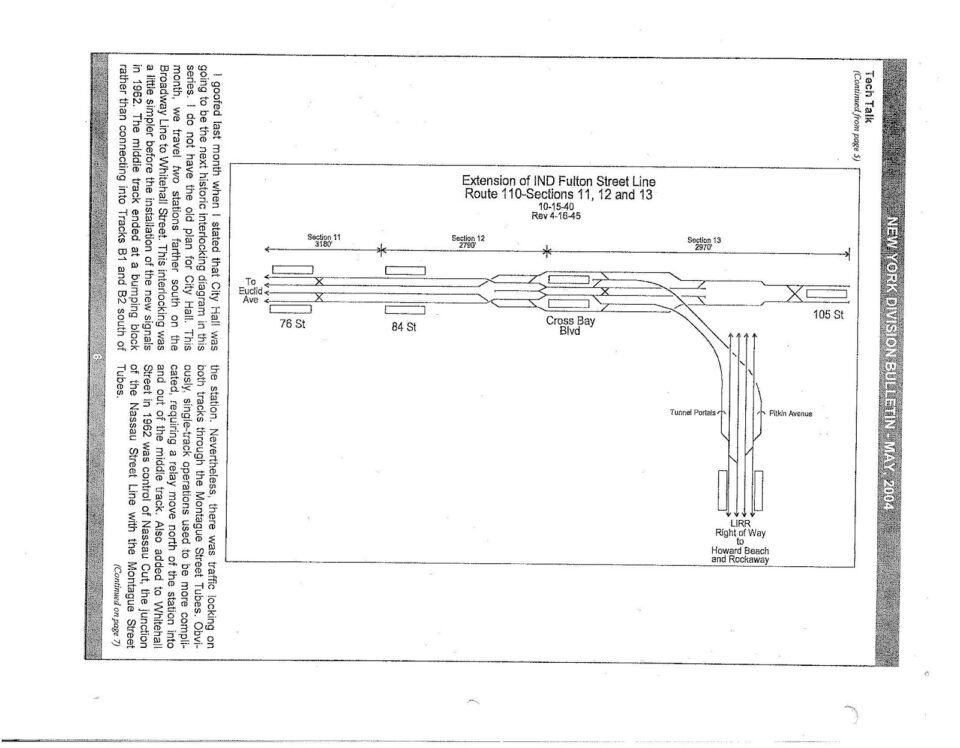

It is clear that in the decade between 1929 and 1939 the IND planners became more realistic about their expansion proposals. The entire Myrtle-Rockaway Line, with the Winfield Spur and Crosstown Line connection, was dropped. The Van Wyck Blvd branch remained, but the Liberty Ave extension was eliminated in favor of simply extending the IND Fulton St Line further east. The Rockaway Beach Branch connection was simplified to be a branch off of the QBL.

In Queens, the QBL had been planned and built so that only express trains would connect Manhattan and the borough; all local traffic would head to Brooklyn via the Crosstown Line. But Manhattan-bound service proved too dominant and planners realized their mistake. The 6th Ave Line, opened in 1940, provided more express service to Queens, but the 2-track 53rd St Tunnel was still a choke point. Planners left provisions in the complex 53rd St interlocking for a future second tunnel.

In 1940 the city purchased the bankrupt private IRT and BMT, merging them with the IND, but all expansion was halted during World War II. After the war, planners got back to work on extending the subway into Queens, but with more limited ambitions. Construction of the IND Fulton St Line had been delayed by the war and was finally extended from Rockaway Ave to Euclid Ave in 1948. Provisions for a planned extension to the Aqueduct Racetrack and connection to the Rockaway Beach Branch (above) were built, but the line was dropped in favor of reusing the elevated Liberty Ave Line. The extension to Aqueduct was to allow for a future extension of the line into South Jamaica, but the abandonment of this section ended any hope for new subway service to the neighborhood.

The Hillside Ave Line had been built up to 169th St, but as this was not intended to be a terminal, the track and switch layouts limited capacity; In 1950 the city opened a one-stop extension that also featured a massive, dual-level 8-track yard. These were the final sections of “original” IND plans to be completed.

The city had exhausted its ability to fund transit operations and expansion so the New York Transit Authority was created in 1953. With more limited funding, the new authority scaled back expansion plans to focus on new, but important connections.

To increase capacity and service to Manhattan on the QBL, a connection between the BMT 60th St Tunnel and the QBL was built (known as the 11th St Connection) which allowed Broadway trains to operate on the QBL (today, the R train. At the time, the EE train). The IND Fulton St Line was finally connected to the recaptured BMT Liberty Ave Line to Lefferts Blvd, and the newly acquired Rockaway Beach Branch was connected to the Liberty Ave Line, both in 1956. These were the last miles of new subway tracks opened for another decade.

While these connections provided much better service to Queens, they paled in comparison to the amount of money that the federal government was pouring into new highways. In the 1930s, master builder Robert Moses had constructed the Belt Parkway, Grand Central Parkway, and Cross Island Parkways in Queens. After the war, he was able to build the Whitestone Expy, Van Wyck Expy, Long Island Expy, and Clearview Expy. These roads, rather than subways, laid the foundation for a more auto-centric development pattern in eastern Queens.

Post War

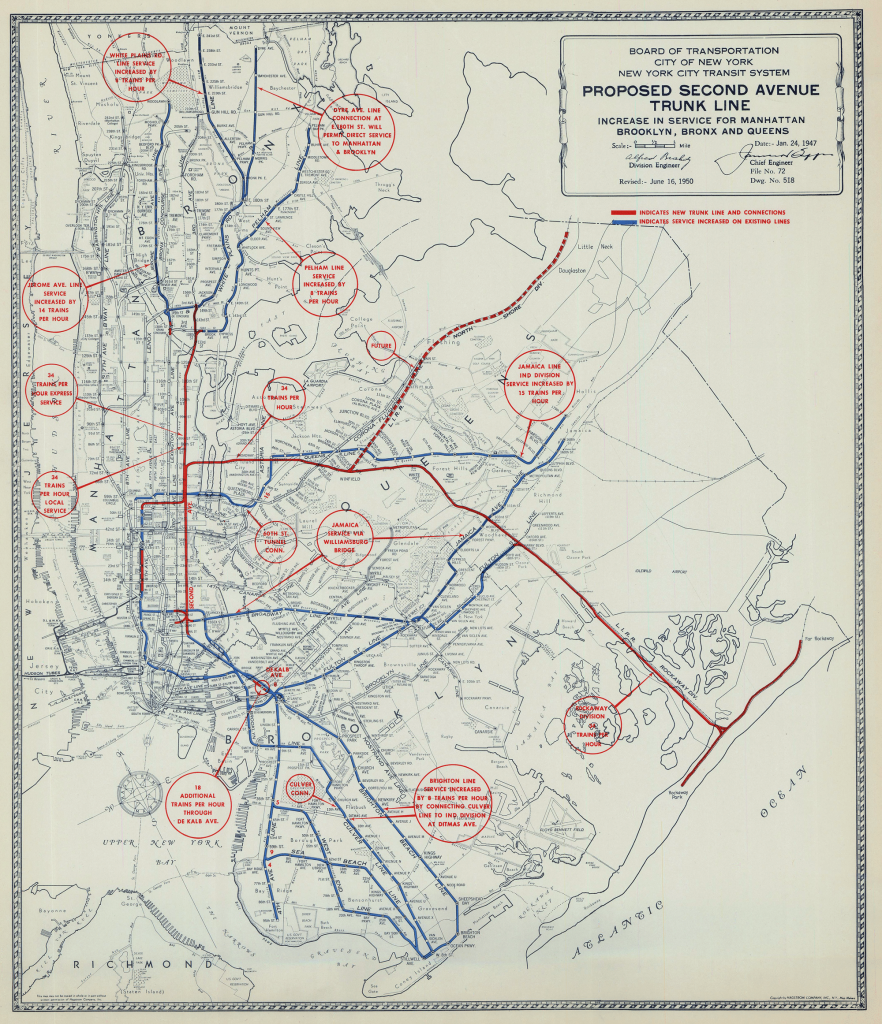

In the 1950s, subway planners were focused on maintaining the system over expansion. The only major expansion plan was centered around the 2nd Ave trunk subway. The plans called for improvements to service in the Bronx, Manhattan and Brooklyn. A new East River Tunnel was proposed, connecting the 6th Ave and 2nd Ave lines to Long Island City. The vaguely located line would have linked up to the LIRR at Winfield Junction, where it was proposed to take over the Port Washington and Rockaway Beach Branch lines. Service to Rockaway was more practical after the city had purchased the line from the LIRR, but service along the Port Washington was always slated for some undetermined future date.

At this time the LIRR was facing the same problems as the subway; Old infrastructure and deferred maintenance meant that service was poor while the fares were expensive. The new highways built by Moses meant that the population of Nassau Co. was exploding, but these new residents were driving instead of taking the train. The LIRR considered cutting branches to save money. This was similar to the private railroads across the nation as passengers left for their cars.

It was at this time that transit planners began to drop grand, expensive new tunnel plans for more cost-effective routes along existing rail lines. This was nothing new as all the subway lines which run to Coney Island were once steam railroads, and both the Rockaway Beach Branch and Dyre Ave Line in the Bronx were defunct commuter rail lines.

The ambitious 2nd Ave trunk line plans of the 1950s were dropped once it became clear that the $500 million bond which had been raised to fund the project had instead been spent on keeping the existing network from falling apart. With Moses’s new roads draining ridership away, planners had to completely rethink what was needed to improve mass transit. Past subway riders were buying cars and moving to the suburbs, and all the new highways weren’t bringing traffic relief. Planners saw that providing fast mass transit to the new edges of the city needed to be the priority.

A New Tunnel Evolves

By the 1960s the Midtown business district was booming and shifting ridership away from Lower Manhattan. Trains on the QBL were packed and planners moved their focus away from serving Lower Manhattan and Brooklyn to serving Midtown and Queens.

In 1963 planners proposed a new East River rail tunnel which would provide more capacity to the QBL. The original plan called for extending the 6th Ave Line up to 77th St and running to Astoria with a connection to the QBL at Steinway St. Test bores in the river found that it would be considerably more difficult to build a new tunnel that far north, so the location was moved to between 64th and 61st Sts, with a connection to the QBL near Queens Plaza. 63rd St was chosen after the Rockefeller Institute objected to the tunnel running through their campus; they argued that the vibrations would mess with their sensitive equipment.

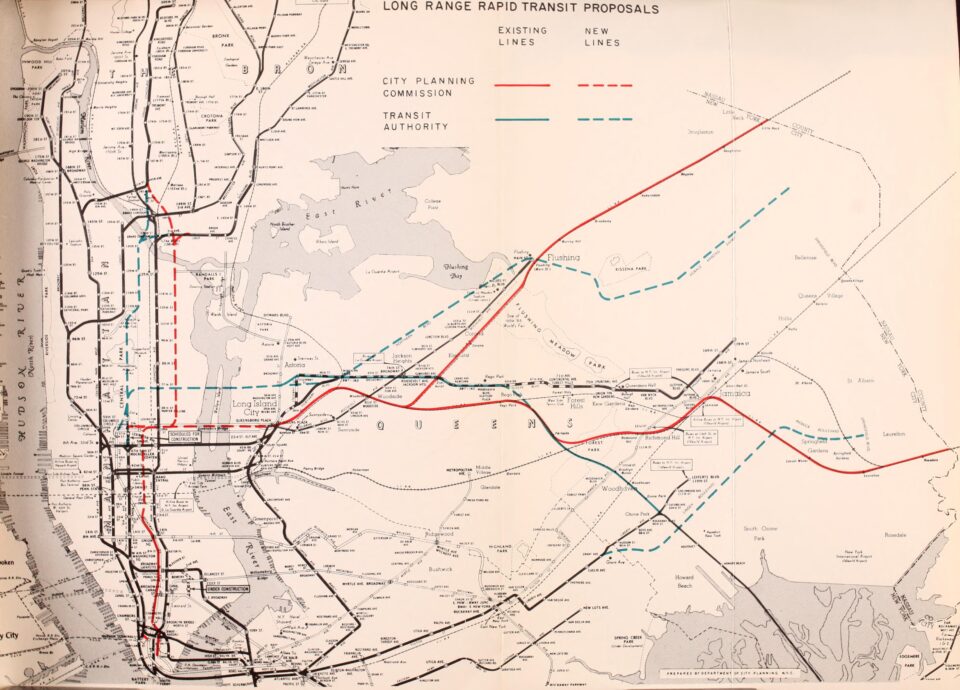

At this time the Transit Authority wanted to scrap a 2nd Ave subway entirely, opting instead for a new line to Queens and a super-express line under Central Park to the south Bronx. The city protested and came up with an alternative plan, keeping 2nd Ave north of 59th St and providing a branch to Queens, with connections to the 6th Ave Line and a new subway along Madison Ave.

In Queens, the city proposed connecting this new tunnel to the LIRR, with more frequent service on the Port Washington Line and new service along the northern end of the Rockaway Beach Branch, connecting to the Lower Montauk and Atlantic Lines to Rosedale. This was the first seed of the Southeast Queens Line. This service would have been closer to the RER in Paris, a hybrid mass transit on commuter rail lines.

The LIRR fought back against this hybrid concept but still saw the advantage of a new crossing. Planners had long seen the need for better access to the burgeoning office district around Grand Central. A second level was added to the tunnel so that LIRR trains could reach the east side. The original scheme called for a single LIRR track along 63rd St for trains to loop up to Grand Central, then go back to Queens. A dispute between the NY Central Railroad and LIRR ended any track sharing at Grand Central, so a new terminal was proposed under 3rd Ave for LIRR trains.

While there seemed to be a consensus that a new tunnel to Queens was needed, no one knew quite where it would go. Once the location of the tunnel was settled on at 63rd St, planners knew they could tie it into provisions left in the Broadway and 6th Ave Lines. In a masterstroke, the new 63rd St Tunnel would be the crux of an ambitious new network that would tie Midtown and 2nd Ave together with new lines in Queens.

Route 131

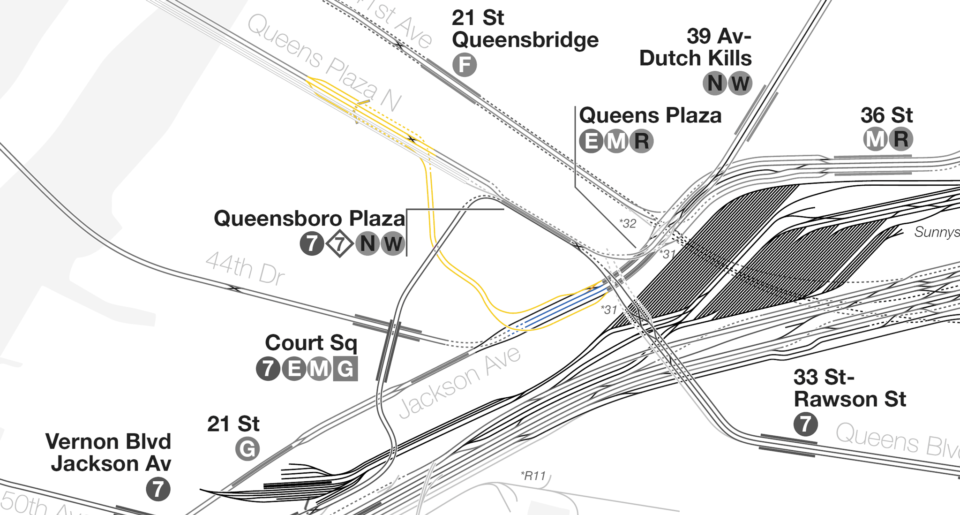

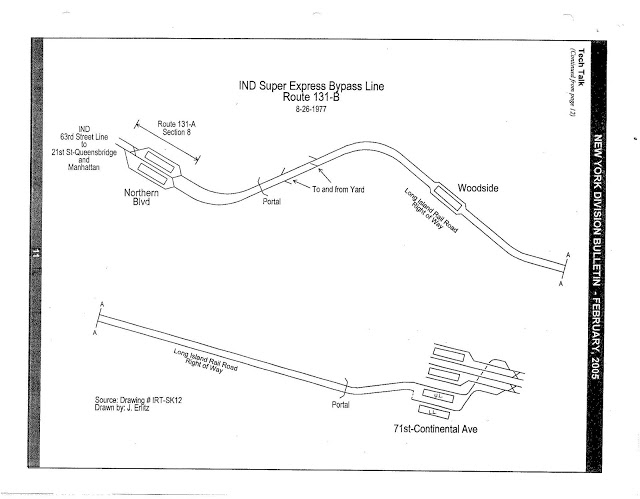

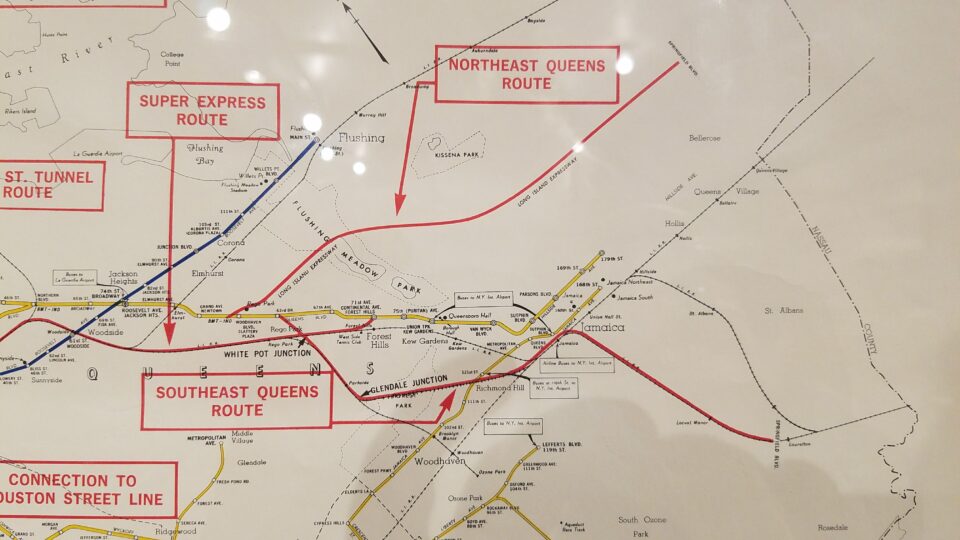

Subway planners settled on a modular approach to expansion. The entire new line was dubbed Route 131. The 63rd St Tunnel (Route 131-A) would connect the Broadway, 6th Ave and 2nd Ave lines directly to the QBL, providing more service to Manhattan. Original plans called for a complex set of flyovers at Queens Plaza for 63rd St trains connecting to the QBL with 53rd St trains branching off to serve the proposed Super-express. This was simplified to simply running 63rd St trains through to Sunnyside Yards with a transfer station at Northern Blvd.

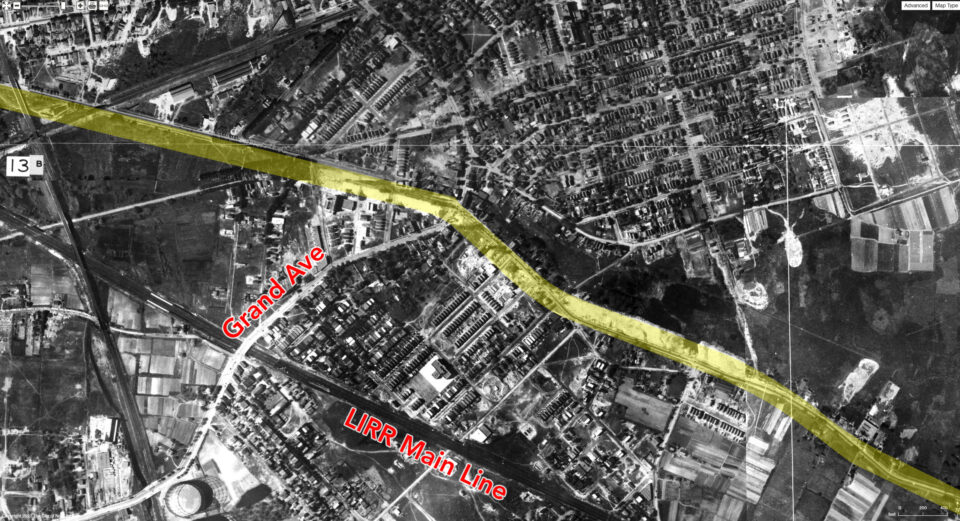

Past Sunnyside Yards the Super-express tracks would run along the LIRR Main Line out to Forest Hills (Route 131-B). The LIRR Main Line was built with space for 6 tracks between Harold Interlocking (Sunnyside Yards) and Jamaica. Through Woodside the 5th and 6th set of tracks are used by the Port Washington Branch. It was proposed that 90 private buildings would need to have been taken between Sunnyside and Winfield Junction and there was not enough space along the ROW.

After Winfield Junction, these tracks were used by the Rockaway Beach Branch. But with the Rockaway Branch having been abandoned in 1962, they were free to be used for this new service. The tracks would dive underground near Yellowstone Blvd and stop at a new lower-level platform at 71st Ave-Continental station, after which they would connect to the local tracks of the QBL. This would increase overall capacity and reduce delays associated with local riders transferring to express trains.

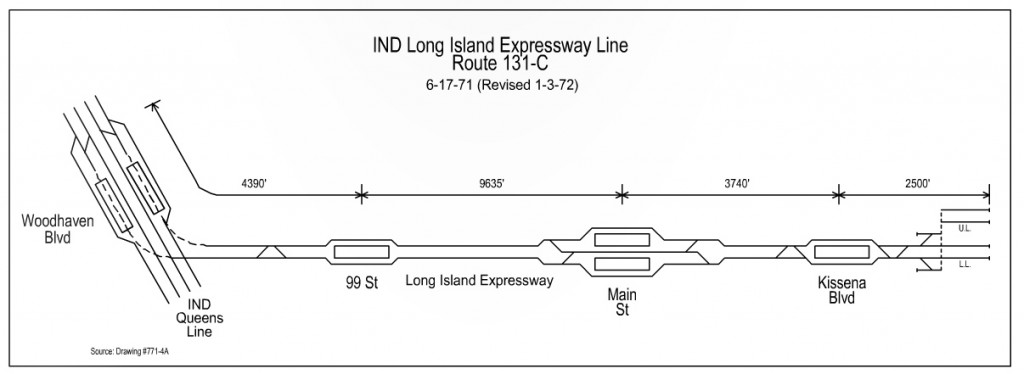

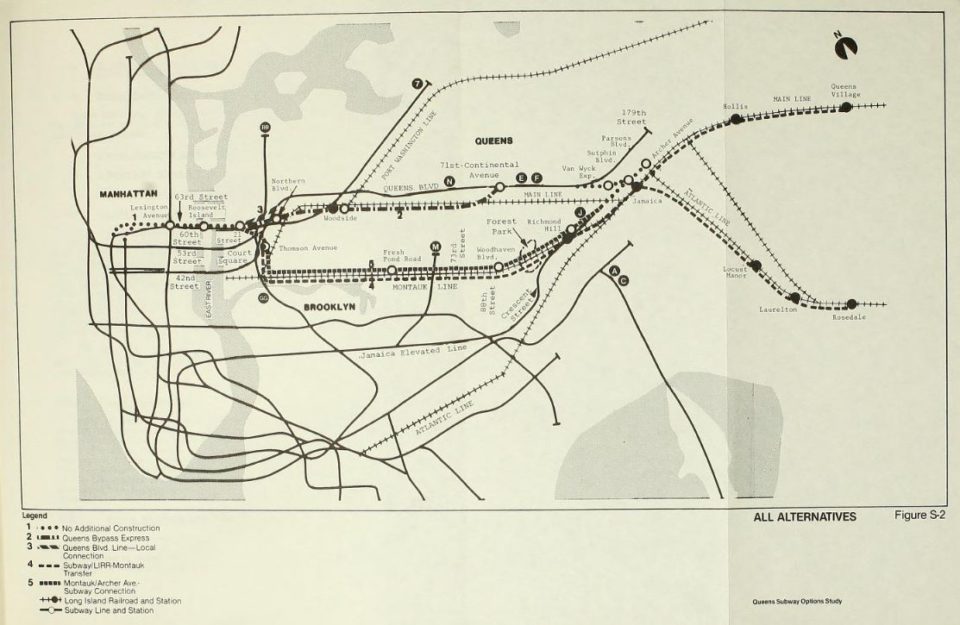

With additional service from the Super-express tracks, new branches could be built deeper into Queens without overloading the QBL. Two branches were proposed: a Northeast Queens Line (Route 131-C) along the Long Island Expy into Flushing, and a Southeast Queens Line (Route 131-D) which would have branched off the QBL using the Rockaway Beach Branch provisions built at 63rd Dr station.

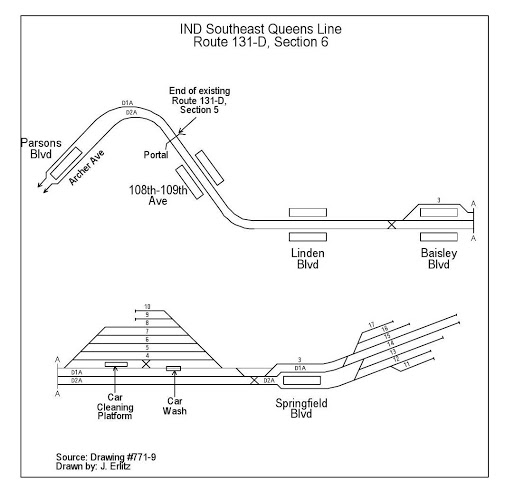

The Southeast Line (SEL) would have run along the Rockaway Branch until Metropolitan Ave where it would have connected to the LIRR Lower Montauk Line and run through Jamaica. The line would have run above ground with stops at Parkside (Metropolitan Ave) and Richmond Hill. After Jamaica the subway was to run along the LIRR Atlantic Branch to Springfield Blvd, either as a replacement or alongside the LIRR tracks.

It was at this time that local Queens leaders began pushing to revitalize the core shopping district in downtown Jamaica. The Jamaica El had been extended along Jamaica Ave to 168th St in 1918 and many residents resented how it had dominated the street. With the typical suburban white-flight of the post-War years, the shops in downtown Jamaica had fallen on hard times. Leaders pointed to the El train as a deterrent to development and an overall blight to the neighborhood.

The new subway service through Jamaica was seen as a perfect opportunity to replace the El. The problem was that the new service would only connect riders to Queens Blvd; removing the El would cut off riders coming from Brooklyn. The plans for the SEL were expanded from a 2-track above ground line to a 4-track underground subway with 2 tracks for QBL service and 2 tracks for replacement Jamaica Line service.

To accomplish this, and to save on costs, the section of the SEL through Forest Hills was dropped in favor of a shorter connection in Jamaica using the provisions built for a subway branch under Van Wyck Blvd. A new subway was proposed under Archer Ave to connect the existing lines in the area with the LIRR Jamaica station complex. This new subway would then allow for two branches deeper into Jamaica to be added. The connection to the QBL would extend that service to Springfield Blvd along the LIRR Atlantic Branch and the connection to the Jamaica Line would extend that service further along Archer Ave to Hollis.

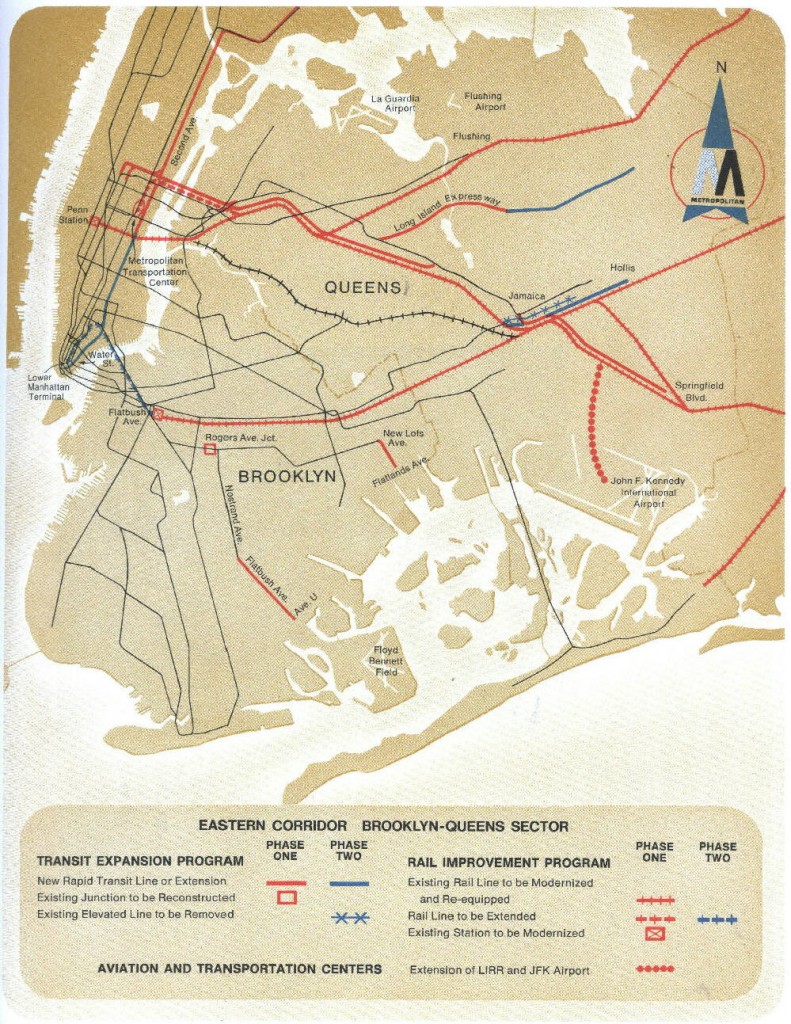

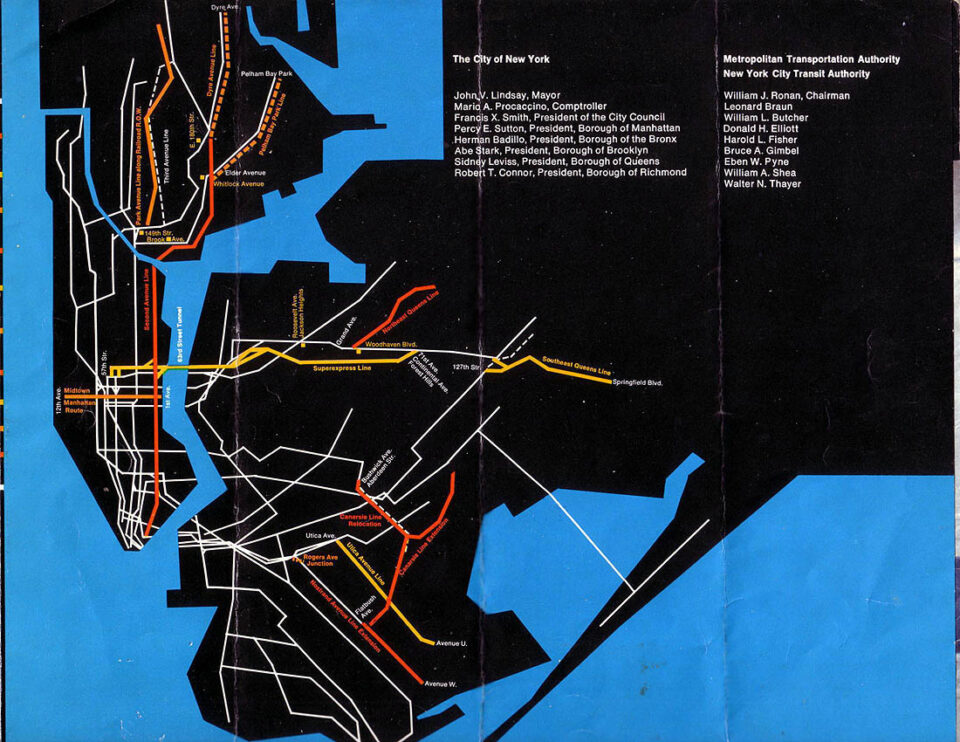

In 1968 the Metropolitan Transportation Authority was created to merge the failing commuter rail lines with the subway, buses, and Triboro Bridge and Tunnel Authority. The concept was to use the profits from the TBTA to shore up and expand mass transit. In order to build political support for the action, MTA promotors laid out the largest expansion plan since the IND Second System. The first phase focused on the 2nd Ave subway from the Bronx to 34th St and the 63rd St/Super-express Line with Northeast and Southeast branches. The Brooklyn IRT lines were to be extended, as well as electrification of the LIRR, a branch to JFK Airport, and replacement of the 3rd Ave El in the Bronx.

The crux of the two new trunk lines revolved around the 63rd St Tunnel, so construction was planned to begin there first. The MTA hit the ground running with more enthusiasm than sense; Construction began on the 63rd St Line in 1969. In 1972, the MTA broke ground on both the 2nd Ave subway and Jamaica El replacement, the Archer Ave Lines. Funding was supposed to come from a mix of MTA, city, and Federal sources. But a perfect storm was brewing that would bring the mighty dreams to heel.

Downfall

The history of the New York subway may not repeat itself, but it surely does rhyme. A month after the city published its IND Second System in 1929 the stock market crashed and reigned in the ambitions of a generation. In the 1970s a similar fiscal calamity brought down the dreams of a new generation of planners. Years of deficit spending had maxed out the credit of the city of New York. The stream of Federal funds that had been running for two decades was cut off. The deferred maintenance of the subway system turned out to be much worse than the new MTA could afford to address. The vast expansion quickly ground to a halt.

By 1974 construction on the new lines was becoming tenuous. Original plans for completion of the 2nd Ave subway and Route 131 were to be in 1980. Delays began to mount and the costs of construction ballooned. In 1975, Mayor Abe Beame decided to cancel any further work on the 2nd Ave subway and move funds to the two Queens tunnels, as they would be able to become operational sooner. Opening date for the Queens lines was pushed to 1983.

As delays and construction problems mounted (the tunnels had both a fire and flooding problems), the federal government threatened to not only stop paying for the line, but ask for the funds back if the work after the MTA said it might have to abandon the work. To save money, the planned Northeast and Southeast branches were canceled. In 1976, the Super-express line was shelved and the opening of the 63rd St Tunnel and Archer Ave subway was pushed back to 1987. Funds were delayed when a Federal investigation began looking into the construction problems. While there had been shoddy work and poor management, no criminal wrongdoing was found. Funds were released to finish construction.

In 1988 the Archer Ave Lines finally opened, serving the E along the QBL and the J/Z along the Jamaica Line. A year later the 63rd St tunnel opened, although it ended abruptly at 21st St-Queensbridge station with no connection to the QBL. 20 years after the MTA hit the ground with an ambitious plan to expand the subway by 40 miles, all it had to show for it was 5.5 miles of new tunnels. Ironically, the subway system was shorter now as in the 1970s the MTA demolished the 3rd Ave El, Myrtle Ave El, and the end of the Jamaica El.

The end of this chapter comes in 1992 when the MTA began to plan for how to connect the 63rd St tunnel stub to the rest of Queens. Planners looked at 4 options: a simple direct connection to the local tracks of the QBL, the super-express along the LIRR to Forest Hills, a short tunnel to Sunnyside Yards with a transfer to the LIRR, or an extension of the line along the LIRR Lower Montauk Branch to Jamaica.

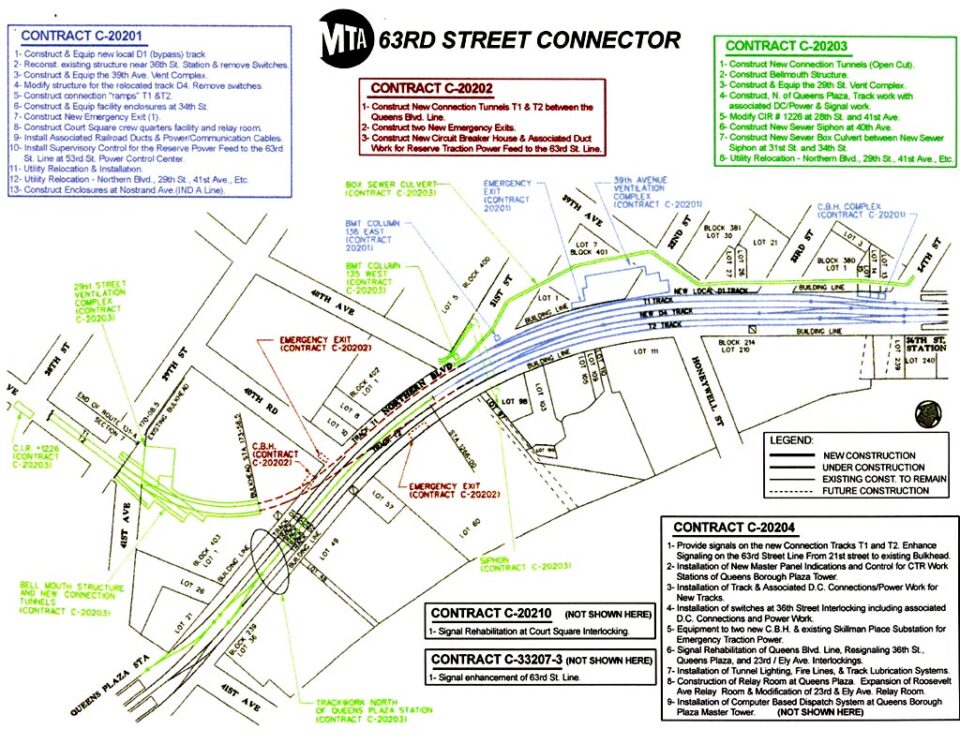

With funding tight and the Lower Montauk alternative not popular with locals, the MTA chose to go with the most obvious choice, connecting the 63rd St tunnel directly to the QBL. Unlike the proposed alternative, the MTA (rightly) chose to connect the tunnel to both the local and express tracks. This required more complex and costly reconstruction of the QBL under Northern Blvd, but provided the line with more flexibility as well as capacity. This connection was opened in December 2001.

The lower level of the 63rd St Tunnel sat empty until 2007 when the MTA began work on the East Side Access project (today Grand Central Madison) with the aim of extending the LIRR to a new terminal under Grand Central. This project was first on the chopping block when the MTA had to pair back its 1968 Plan for Action. A turf war between the LIRR and Metro North meant that the new terminal could not use existing tracks at Grand Central Terminal, but rather had to have an expensive new underground facility constructed. The project has faced its own controversy, cost overruns and delays but is planned to open at the end of 2022, 53 years after ground was broken for the tunnel.

Conclusion

The sad irony of the story of Route 131 is that the whole point was to save money by incorporating existing lines into the network quickly. Yet, due to a number of factors, this proved to be more difficult than planners could imagine. The required connections, while small in the grand scheme of things, required so much work that the “cheaper” branches had to be cut.

It is easy to understand why the entire line is considered forgotten. With the important connections at 63rd St and Archer Ave finally being completed, the lack of extended service makes these lines feel as if they were always part of the subway. Except for the former V train, now the rerouted M, there was no new service which ran along Route 131.

It should not be a surprise that planners have forgotten about these branches, like the Southeast Line. It took so long for 63rd and Archer to be built that any transit planner would have retired out by now. The MTA, with its lack-luster track record for effective construction, would be forgiven for focusing on other projects (such as 2nd Ave) after taking 20 years to build 5.5 miles into Queens.

Today, when transit equity is coming to the forefront of planning, we must be thankful that these projects, however small, were finally built. Now we have the foundation for serving transit deserts as well as improving system capacity.

In Part 2 of this post I will look at the specifics of the unbuilt Southeast Queens Line (based off of the 1978 feasability study) and see just how it might work today.

Nicely done! Had I known you were going to use my track diagrams, I would’ve sent you clean PDFs of them, which I still can do, if you like! Keep up the interesting work!

Please do!