“if all you have is a hammer, everything looks like a nail”

-Abraham Maslow

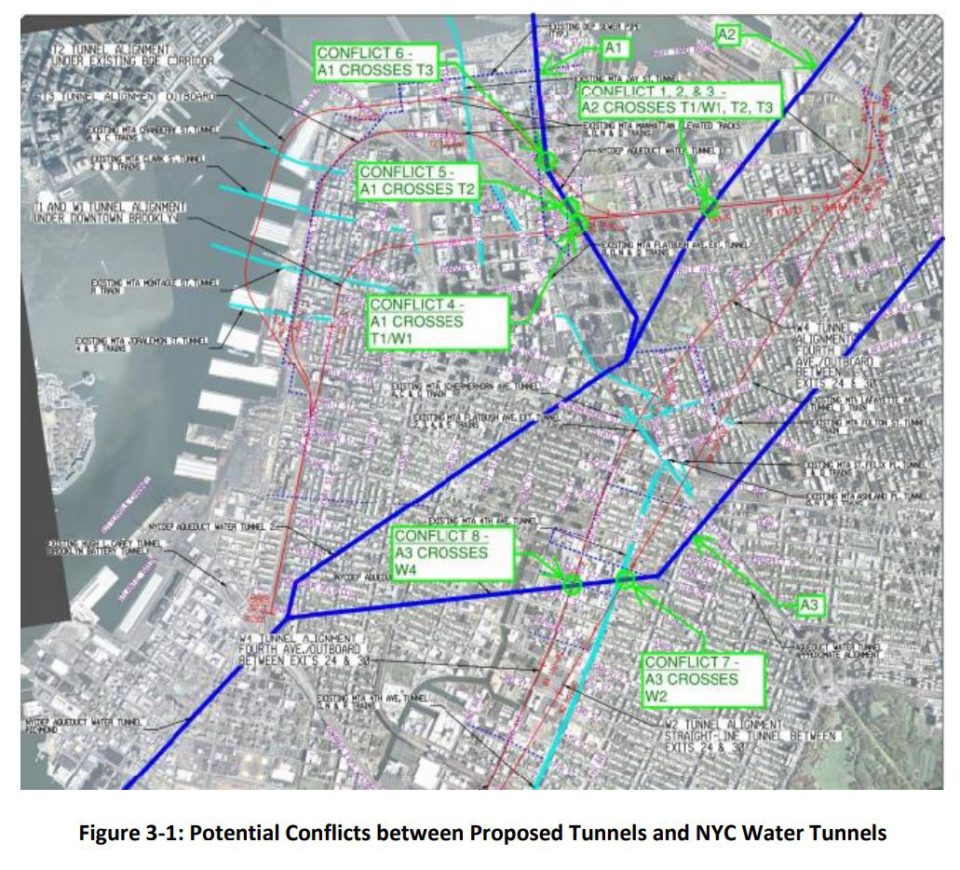

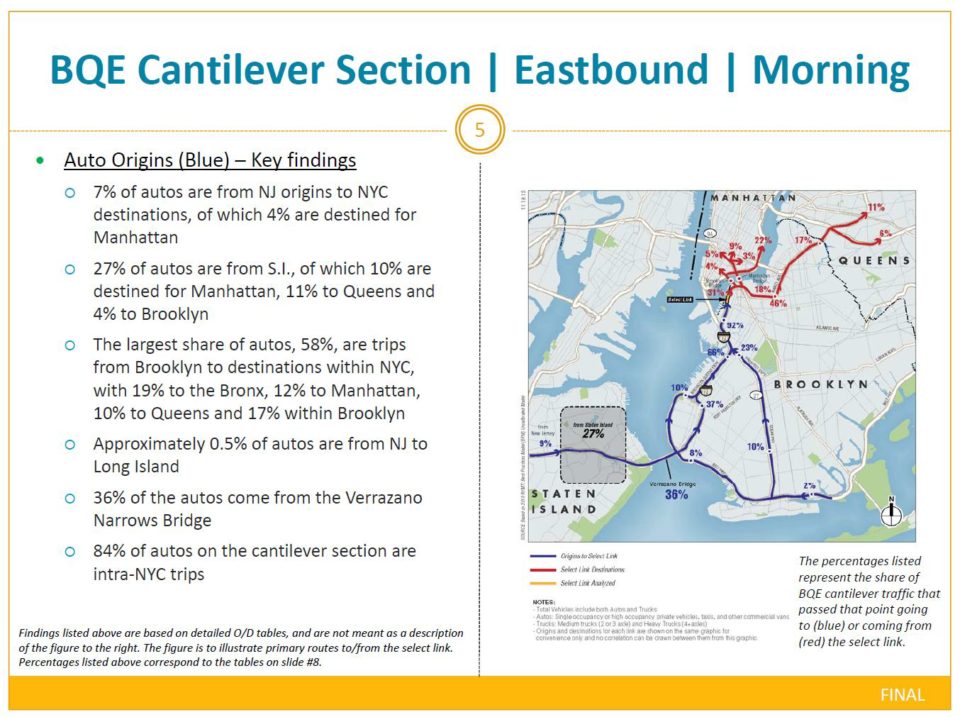

It should be no surprise that to every highway engineer the solution to traffic is always more roads. In this case, it is the NYC DOT, which last week announced their initial plan to rebuild the crumbling Brooklyn Heights cantilevered section of the BQE from Atlantic Ave to Sands St. The DOT had originally been looking at building a tunnel to replace the structure, but apparently the presence of a major city water tunnel directly in the path of any reasonable alignment, not to mention the network of subway tunnels, nixed any tunnel plan for good. The new plan involves building a temporary elevated highway alongside the existing one while they rebuild it. Naturally, the neighbors in Brooklyn Heights are not too pleased with such a plan. At a recent raucous town hall meeting (you can watch all 3.5 hours here) residents warily asked how this new structure would negatively impact them, with one person even suggesting DOT builds the structure further west through Brooklyn Bridge Park, which sparked loud applause.

One thing that DOT took away from this meeting was that the public is, rightfully, skeptical of their plans. A hard thing for professionals to understand is that they need to show their work in a way that the layman can follow along — just presenting a final plan will spark outrage unless people understand why it is the chosen alternative and why the others may not work. But in her opening statement DOT Commissioner Polly Trottenberg pointed out that the NYC DOT is a single city entity, not connected to the MTA or Port Authority and thus cannot impose bridge tolls or increase subway service. Other possibilities, like congestion pricing, is beyond the scope of this project.

And therein lies the key problem: due to our fractured political system for building and maintaining infrastructure we often cannot implement sensible or affordable solutions.

Make no mistake, this is by design: the DOT exists to handle traffic. If fewer people drove then the DOT would need less money, fewer resources, and provide fewer jobs. Thus it is in their interest to build a new highway, otherwise commuters would take mass transit and funding would be lost. The DOT provides a necessary service of maintaining our roads and bridges, but there is a tipping point where they begin to justify large projects only as a self-sustaining act. Well known to traffic engineers and urban planner is the concept of induced demand where building new roads, or more technically providing more capacity and a faster route, only encourages more people to drive. In the end it is often found that traffic is WORSE after a new highway is open. This, famously, was Robert Moses’s trick for justifying building ever more roads and bridges.

In the case of the BQE rehab the DOT is upfront that they are only going to consider an option which involves more roads. This is a typical case of confirmation bias on behalf of road builders. But the flip side to induced demand is when you remove a highway drivers will simply find another way. The DOT counters this with an argument that downtown Brooklyn streets are already packed during the day, so dumping thousands of new cars into the streets will bring the city to a halt.

Except this won’t happen. In truth if the DOT was to simply shut down the BQE for an extended period of time commuters would simply find another route. This is linked to Braess paradox which states:

“For each point of a road network, let there be given the number of cars starting from it, and the destination of the cars. Under these conditions one wishes to estimate the distribution of traffic flow. Whether one street is preferable to another depends not only on the quality of the road, but also on the density of the flow. If every driver takes the path that looks most favorable to him, the resultant running times need not be minimal. Furthermore, it is indicated by an example that an extension of the road network may cause a redistribution of the traffic that results in longer individual running times.”

The DOT knows that without a single preferred route drivers will use any number of other streets, opt for mass transit, or not drive through downtown Brooklyn at all. But DOT planners have to use all the red lines on a map to scare ignorant laymen into believing it will cause mass traffic jams. However, they would never admit to this because it would conflict with their core mission: providing more space for cars. This phenomenon has been witnessed in cities around the world when highways are shut down, even in car-centric Los Angeles which was preparing for Carmageddon when the 405 freeway was to be shut down for a bridge replacement. Famously, nothing happened: drivers found another way, or chose to not make trips at all. Back in New York, we have a better way already.

The Subway Option

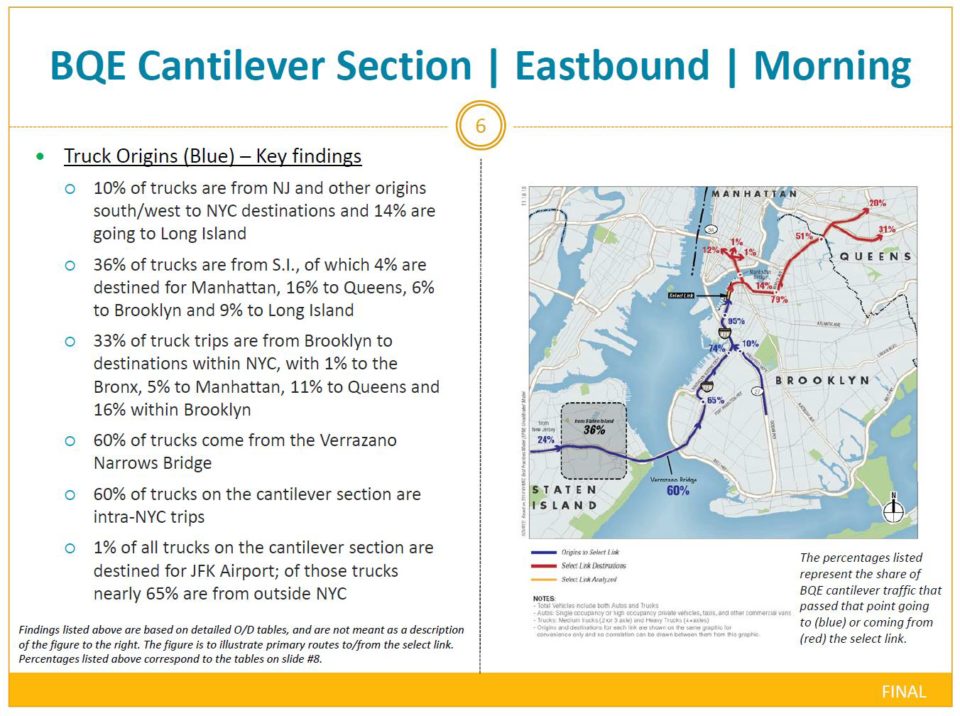

New York has a giant web of subway lines, which even in their sad present state still work remarkably well and allows most New Yorkers to live their lives never having to own a car. Because highways often promote sprawling development it’s harder for suburban drivers to switch to mass transit as an alternative. But Brooklyn was mostly developed before the highways were slashed through and the subways still serve the borough relatively well. This means that we have a mass transit network in place which could take over the burden of most of the traffic currently using the BQE. The DOT’s own numbers tell the tale. Up to 2/3 of the traffic using this section of the BQE are intra-borough trips (this is car traffic, not truck, which I’ll address later). If the BQE was shut down without a complicated second highway to pick up the current traffic then large portions of users could switch to mass transit. The DOT, by their own admission, would not consider this since the MTA is a state agency in which they have no say, and admitting that their own users could use a different service altogether would be an admission that their highway doesn’t need to exist.

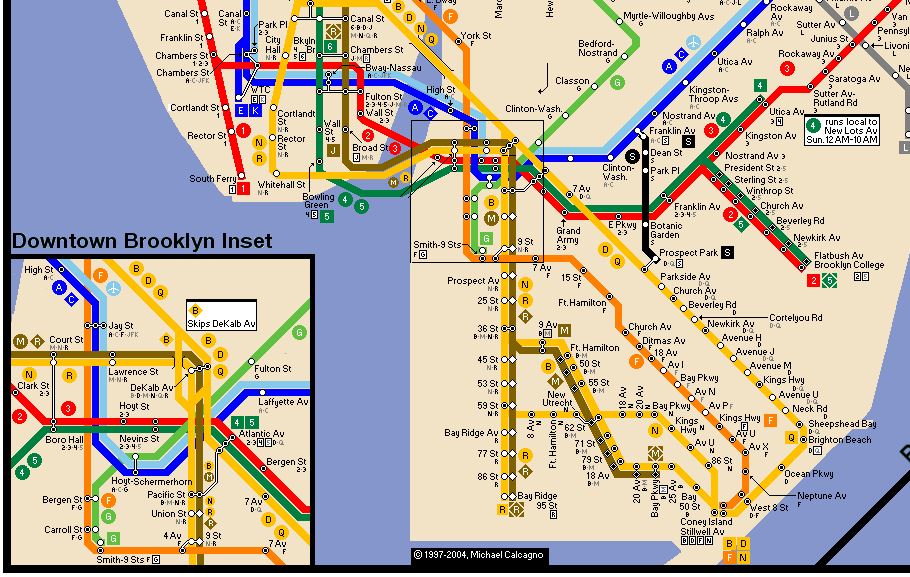

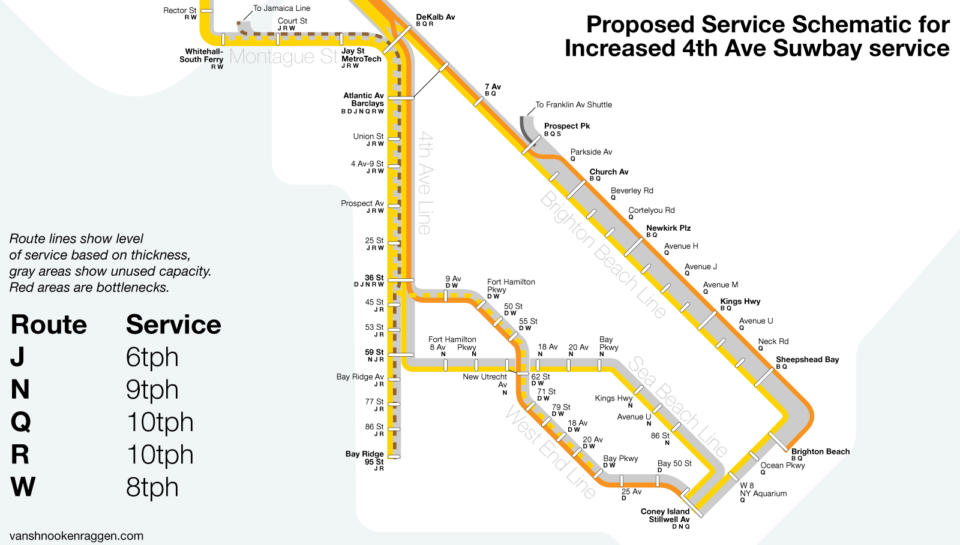

Of course, the MTA in its current state could probably not easily handle the extra traffic. While southern Brooklyn is well served by subway lines, the service on these lines is lacking. Bad routing has created bottlenecks which limit service on the B,D,N,Q, and R trains. I outlined an alternative solution for this problem but service could be improved even without an expensive new yard.

Currently both J and W trains terminate in lower Manhattan. When the BMT Nassau St Subway was built it was the last link in a great subway loop network. Trains from northern and eastern Brooklyn would swing through the Lower East Side and Financial District and loop back into southern Brooklyn. However, as new subway lines replaced the old elevated lines and jobs in lower Manhattan began moving to midtown this loop service began to be less effective.

Previously M trains looped south to Bay Ridge or Coney Island. There were even rush hour R trains between Bay Ridge and Chambers St. As recently as 2010 there were rush hour M trains making the journey down to Bay Parkway to allow for super-express D trains in Brooklyn (budget cuts combined the M and V trains to reroute M trains through midtown and back into Queens, which has been a popular change).

The main reason J and W trains terminate in lower Manhattan is more rational than technical. J trains terminate at Broad St because there isn’t enough demand between lower Manhattan and Brooklyn for a train which doesn’t go to midtown. W trains terminate at Whitehall St due to a lack of yard access in Astoria. But in the mornings and evenings there are a number of W trains which start at the 86th St station in southern Brooklyn so they can access the Coney Island Yard. The Montague Tunnel, through which the R train runs, only sees up to 10 trains per hour at rush hour since R trains are limited by a bottleneck in Queens. This leaves plenty of space for extending J and W trains south during the day. W trains would continue along the D to Bay Parkway, allowing some D trains to run express, while J trains would service Bay Ridge. This would more than double service along 4th Ave and southern Brooklyn.

Some may argue against this increase in service since it would only add local service; express trains are maxed out. But there is more to a commute than how long a train takes to get from A to B. Wait time is often more of an impact on ridership than travel time. Wait times along the R in southern Brooklyn are notoriously long to the point that, even with traffic, it’s often faster to drive. At 10tph a rider must wait AT LEAST 6 minutes for the next train (more often it is much longer) and, as is often the case, must transfer to a midtown bound express that could also have another 6 min wait. That is up to 12 min of just waiting, at rush hour no less. But with added local trains, that wait time could be cut in half. A potential rider knows that a train is only a couple minutes away so it’s worthwhile to wait. Since riders are already going to transfer to express trains to midtown, extending the J, which doesn’t go to midtown, still helps reduce the overall trip time. Crowding at transfer stations on the R in Brooklyn can reach dangerous levels during rush hour and cause delays due to boarding. More trains means less crowding and fewer delays which speeds up the entire network. Extending the J would also allow riders to have more choices about where they transfer, further reducing crowding at popular stations. Other services could be considered as well, such as bringing back super-express D trains or adding the much-discussed express F train.

(In the case of the schematic above this is just one option. A further study should be done which takes into account the disadvantages of interlining to find the best balance of service. But the point is there are more than a few different ways to increase service to southern Brooklyn.)

It’s not technical, it’s political

Commissioner Trottenberg brings up the point that the city DOT cannot tell the state MTA to add service. Except that Polly Trottenberg sits on the board of the MTA. It’s at best disingenuous to suggest that she has no say in the matter or that the city and state couldn’t–just for once–work together on something so crucial. Furthermore, it turns out that one of the neighbors of the project in Brooklyn Heights to be personally affected is none other than the head of the MTA himself, Joe Lhota. In a now-deleted tweet Lhota said “I always wondered what would turn me into a Community Organizer. This is it. NIMBY (and proud of it)”. The feud between Mayor de Blasio and Governor Cuomo is old hat at this point, but this is an easy win for de Blasio. The costs involved with extending service would be a fraction of building a temporary highway, and not building the road would speed up the reconstruction considerably since the contractor could begin work sooner and not have to work in such dangerous conditions.

A traveler will chose the path of least resistance. No doubt some drivers will still opt to drive, especially commuters from Staten Island and New Jersey . But if there could be even a 25% reduction in driving by the removal of the BQE via an increase in subway service then the local streets wouldn’t see much of an impact. Additionally, the DOT could adjust light timers on more heavily used avenues throughout Brooklyn to handle the offset traffic. What the DOT should then focus on is how to handle the truck traffic which will spill over onto city streets. According to DOT numbers, 79% of trucks are headed to northern Brooklyn with half headed into Queens with slightly fewer headed from Queens into Brooklyn. If the DOT can paint bike lanes everywhere then surely they can have truck lanes on designated roads at the same time; 4th Ave, Atlantic Ave, Flushing Ave for example. But this is exactly what the DOT is trying to avoid. Billions of dollars, prestige and, most importantly, jobs are all at stake.

The alternatives are clear. Whether the DOT wants to take their blinders off is a harder question.

A highway through Brooklyn Heights? Those brownstones would crumbled to the ground if the construction process evens started. Those people are in the right when it comes to being a NIMBY at least just this once. Especially for a city like ours-there is no need for this but better subway service and newer larger lines.

A long term service disruption of a major highway isn’t even out of question for the region. NJDOT closed all traffic lanes going into New York City on the Pulaski Skyway for four years along with periodic outages going the other way. However, that required a lot of coordination with other agencies and the Skyway had several nearby detour routes.

I think the big issue for a temporary closure is going to be truck traffic. There is no good detour between Staten Island and Queens for trucks.

umm… nycsubway.org does not have an extra “s†at the end of “subway.†Also, nice work on all your ideas and I agree that the MTA should extend W and J service if they do repair the BQE.

It’s just a bit over eight years since the M and V were merged as a cost saving move. Has that been such a success that it couldn’t be undone for this? Checking the current schedules, which unfortunately don’t list the shared stations, I interpolate a savings of about nine minutes for the F over the R from Bryant Park to 4th Ave/9th St.

This is one of the most intelligent analyses I’ve read since this debacle was proposed.

I live in the one building that sticks all the way out from the Heights; it touches the Promenade. It’s not just the added highway lanes next to the existing promenade that are bad, but the sidewalk itself would be turned into two lanes, up against the yards of all the houses along the current garden.

The proposal to “stabilize†the existing retaining wall foundation that anchors the triple cantelever involves excavating on the residential side of this foundation, all the way down to the level of the street at the foot of the cliff, and building an interstate at grade on top of the Promenade.

Besides the 1950s lunacy of replacing a deservedly-famous park with a copy of the Jersey Turnpike, we are given the dubious promise of six years of construction.

The Second Avenue subway and Bruckner Boulevard kinda are poor examples of what the City means when someone says “six yearsâ€.

I already have elderly neighbors who are moving away.

Listen to the recording of the DOT presentation: they are so disturbed that traffic will move SLOWLY if the repairs are done one lane at a time.

What could be worse, right? Our mayor feels that six years of an interstate at level with peoples homes, just feet away, is like “pulling off a bandaidâ€. Better that slowing him up on the way to the gym.

Sorry, I couldn’t help that last crack.

A third of the Brooklyn originating trips on the expressway go to the Bronx. Yet the subway increase proposal doesn’t address increased service there. Maybe because there aren’t a lot of options, what with the Bronx having only one B division corridor and Brooklyn only one A division trunk. What might be doable is extending the B train up Concourse midday. LEX express is maxed out but perhaps some additional runs could be added to the 2.

The second biggest group of trips is within Brooklyn at 29% of the total and looping the J back looks like the best thing to do for that.

Surprisingly there are even more Manhattan than Queens destinations but I wouldn’t think much of that is headed for the Financial District what with the tunnels and bridges. And seven subway services already connect them. So I think more of the faster trips to midtown and uptown via the Rutgers tunnel would be preferable to extending the W.

Why extend the J Train to Bay Ridge-95th Street instead of the W Train? Extending the W there would allow it easier access to Coney Island Yard, whereas the J already has a Yard to access at East New York Yard on it’s own existing line. Other than that, I think the Transit Option is 100% the way to go

In the DOT study they mention that about 2/3s of the traffic on this section of the BQE is intraborough. The J therefore would serve this market better than another line that goes to midtown.

Did you mean to say interborough? While the study shows traffic remaining in Brooklyn to be more than that ending in either Manhattan or Queens there are more trips ending in The Bronx by about 12%. The W extension would add service to the boroughs that placed last and next-to-last so why do that at all unless it supports a more meaningful change?

Since you consider the DeKalb switch to be maxed out at 62% of optimum I can see why you’d be inclined to leave The Bronx out of your solution. But if you’re bring more service down from Queens in the form of the W then how about offsetting some of that by replacing some N runs with Ds? We’d most likely want the W to go down Sea Beach then; we’d have increased service on all three 4th Ave branches.

If we’re looking for more than a genius challenge/ESI type of window dressing here then we should look at making the service attractive to the car drivers by looking at total trip time. Will the delay at one place under construction be great enough to exceed the time consumed by all the stops a local line makes plus the time to get to the boarding station plus the time to get from disembarking station to the destination? To ensure that it’s important to look at route speed and to spread destinations out as much as we can.

That makes the F’s time advantage over the W look pretty important. Maybe splitting the M and V is too big a step so we can shift the E and F mix a bit. Some E runs go out towards the F terminal already so it’d be a minimal effect in Queens. C short runs would cover for the dropped Es on 8th Ave and could also justify keeping some B trains express on CPW and temporarily extended up Concourse.

This is more complicate of course but the complication is primarily in scheduling.

No I meant intra-borough. Most of the trips are within Brooklyn. But you are right, the devil is in the details. I was only advocating the J since it was the lowest hanging fruit for increased service. Perhaps a total review would be needed. The B could be bumped up to full time. There isn’t all that much more you can do without CBTC and deinterlining DeKalb, though adjusting the timers and fixing the merging ops at DeKalb would be a good quick start. Another rational for the J is since riders are going to chose to transfer regardless then all we can shoot for is reduced wait times and more transfer options.

The third bulleted item on the DOT slide for car traffic that you included breaks down the 58% of total car traffic that originates in Brooklyn as 19 – Bronx, 17 – Brooklyn, 12 – Manhattan, and 10 – Queens. Now there is a big blue ‘66%’ label on the map but I took that to mean the amount of traffic fed into the construction section from Gowanus as opposed to Prospect or local.

Still 29 or 67% the Brooklyn only traffic is considerable and the J extension well justified. Keeping the Canarsie Tunnel related G extensions around for this might make sense too.

Wow, I was hate reading your article preparing to explain how wrong you were……until I read the article……..Excellent analysis. Thanks