It amazes me that I’ve had this website, in one form or another, for 10 years now. It started out as a place where I could just keep my files online and then when I discovered my interest in the subways and abandoned infrastructure a place to show off my work (maps and photography). Even today people still seek me out for my urban exploration. The basic story is that one day while walking with a friend through the debris of the Big Dig we happened upon an old subway portal which lead down to the abandoned Haymarket Station (which was relocated in the 1970s). This sparked my interest in urban exploration and I immediately began to look for new sites.

In places like the mid-West where factories have been abandoned for generations now and there isn’t much to replace them you get some pretty spectacular exploration opportunities. But in active cities like Boston and New York (and other, but this is where I’ve been in the last decade) the once abandoned parts of the city have been rediscovered and repurposed through gentrification. Once abandoned row houses are rebuilt, theaters are reopened or turned into schools, and old warehouses are converted into lux condos. This gave urban exploration a new purpose: to beat the approaching wave of development and capture a brief moment before all was lost. That’s a little dramatic for sure since nature will reclaim everything one day. But since I’m here now I want to capture what’s left while it’s still there.

Through my travels exploring mostly abandoned infrastructure I discovered a layer of the city that has been forgotten in our mad dash to throw all of our eggs into the newest, fastest, thing. My grandparents lived next to an abandoned canal system in upstate New York which wasn’t far an abandoned railroad that lead to an abandoned bridge over said canal system. The canal was bested by the rails and the rails were bested by the highway. So when I walk the city streets I see these layers of time very clearly. And in many places they still exist.

When I moved to the Boston area as a young teenager we lived just down the street from a very active commuter bike path. I found later of the Rails-to-Trails program which would convert abandoned rail right-of-ways into paved bike and pedestrian paths. It was a beautiful ride and a very quick way through town; a bike highway in every regard (grade separated and there was even a bike shop right on the path which was like a rest stop on the highway). The path itself had been built after a failed attempt to extend the MBTA Red Line through my town in the 1980s. While I loved the path I also saw it as a double edged sword. In a crowded urban environment it is very expensive to build a brand new right-of-way. Cities expand and traffic gets worse. You can only fit so many cars on the road until you need a more efficient way of transporting people.

Therein lies the fundamental flaw in the American business model, that new is always better. When we elected cars as kings we let the rest of our infrastructure fall apart. Today, when many have finally realized we can’t pave enough lanes to make things any better and a balanced approach is needed, we run into the problem of forgotten infrastructure. In cities all over the US there are tracks that have been ripped up and destroyed for highways that now could be used in alleviating the problems of growth. But there is a new problem: what happens when people are used to these railroads being abandoned? What happens when these abandoned spaces run up against the need for more open space in crowded urban environments?

When I first moved to New York City the first thing I wanted to see wasn’t the Empire State Building, Times Sq, or the Statue of Liberty; it was the High Line. Sure, I could believe abandoned buildings and tunnels are in the heart of Manhattan… but an abandoned elevated railroad? That is just nuts. But there it was. And even more incredible was the fact that while walking atop the tracks you entered into another world ABOVE the city. Walking through a tunnel under the city is an incredible experience but one where you must imagine the city above you. Here you are actually going through the city on a level with no people, through the tree tops as it were. It was quiet in a way that you can’t imagine. Then it was turned into a park, a Rails-to-Trails on a whole new level. Many people thought it was crazy, even Mayor Bloomberg who now takes credit for it was once a detractor. And I have to admit they did an amazing job at creating the High Line Park.

But then a funny thing happened: people started to look at other abandoned infrastructure and think “Hey, that could be a park too!” And worse they thought that building a High Line knock-off would have the same economic effects as the original one did in West Chelsea. Except the thing is North Philadelphia isn’t Chelsea, Manhattan. Neither is Humbolt Park in Chicago or Woodhaven in Queens or any of the other rust belt cities that saw the High Line and said I want some of that too. All the High Line did was allow the already hyper-gentrification in the West Village and Chelsea to continue west. It was fuel to the fire, not the spark itself.

So when I look at all the High Line 2.0s (HL2s) out there I want to take a deep breath for each one and make people realize that it isn’t all flowers and condos. Yes economic development is good and yes parks are good but how do you get people around? These aren’t toxic sites or landfills you are cleaning up to create a nature preserve, these are once very active and important infrastructure parts of a once larger system that still can offer their services which are desperately needed.

Why is it easier to get money to tear down a railroad and turn it into a park than it is to reactivate it and serve just as many or more people?

I want to look at a couple examples around New York City which seem to be in vogue at the moment: the Low Line and the QueensWay.

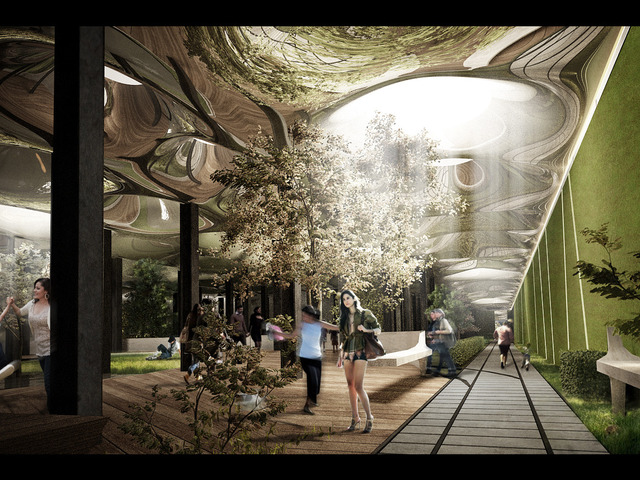

The Low Line is by far the sexiest of the HL2s out there: a subterranean park lit with futuristic fiber optic pods that transmit light from the surface to the underground. May as well be on a spaceship. The space itself was once a large trolley terminal for trolleys coming from Williamsburg. When trolleys were phased out the space was abandoned. Not only that but when ridership declined from Williamsburg to lower Manhattan on the BMT Jamaica Line half of the subway from Essex To to Chambers St was moth balled. That’s right, literally half of the subway on the J/Z line from Chambers St to Essex St is not used. Only half of the Canal and Bowery Stations are in use and while most of Chambers St is open trains only use two platforms (out of 5 but at one point 6).

So you’d think there is some extra space to use down there. But is building an expensive park the right use for it? The Lower East Side was once at the turn of the century considered the densest urban neighborhood in the world due to the slums. 100 years later after much urban renewal the area has changed dramatically. High rise housing projects have transformed a good chunk of the LES and added much needed open space but there is a catch; it isn’t “park” land. It may be a lawn but that doesn’t mean it’s a park. Much of the land that looks like park space down there is off limits and is located in the center of housing projects which may not actually be as dangerous as they look but are still perceived as places that you don’t want to hang around.

At the same time across the river Williamsburg has exploded with development. Take the L or the M train and you will see the crush of commuters in the mornings and nights. Even weekend service has had to be adjusted because so many people commute between the boroughs. And with major projects in the works like the redevelopment of the Domino Sugar plant one doesn’t have to argue too hard of the need for improved transportation. Unlike the Hudson Yards which the mayor so generously bought the IRT 7 Line extension for no one has stepped forth to suggest improved subway or other transit services for Williamsburg.

So with the need for more and better transit service between Manhattan and Brooklyn and the dearth of underused open space in this area of the LES it begs the question: is building a futuristic underground “park” the best use of our money? More to the point if it was built the Low Line would need to have an income stream to make it sustainable. Sure a theater or community space might bring in some dollars but nowhere near what it would take to make it last. And there are plenty of other spots throughout the LES that could be opened up for similar uses for much less (look no further than under the elevated part of the Williamsburg Bridge which is 8 city blocks of parking.

The land adjacent to the proposed Low Line is now being planned for a massive urban renewal program which will add thousands of apartments, offices, retail, and community space. The new and old residents of the LES need real parks to use, not a tourist attraction. The Low Line will also be built in the only available space for improved transit service between boroughs that doesn’t involve building new tunnels under the East River. It isn’t hard to imagine that when offices open at the former Dumbo factory that many of the workers will live in the LES. The space in the old trolley terminal would be perfect for a third subway platform at the Essex St station or even more radical (but not really) would be to bring back trolleys with a new light rail system connecting Brooklyn to Manhattan once again. Building light rail would be a much cheaper alternative to expanding subway service and would work better in the outer boroughs than in congested Manhattan.

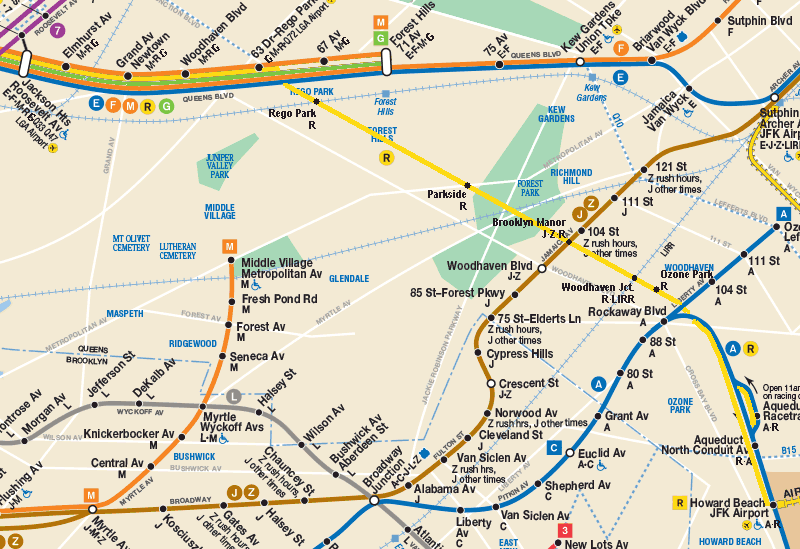

The QueensWay is a more typical Rails-to-Trails proposal but is along a much more crucial transportation link. Many of the traditional Rails-to-Trails are throughout suburbs and rural areas that may be already served by transit of some type. In the late 1800s the railroad boom lead to many lines over building in areas (and lead to a nasty economic collapse) so it’s a safe bet that in many places there won’t be the need for a extra railroad. But the only railroad through New York City that could directly connect both JFK Airport and the Rockaways directly to Penn Station and Midtown Manhattan? That’s important.

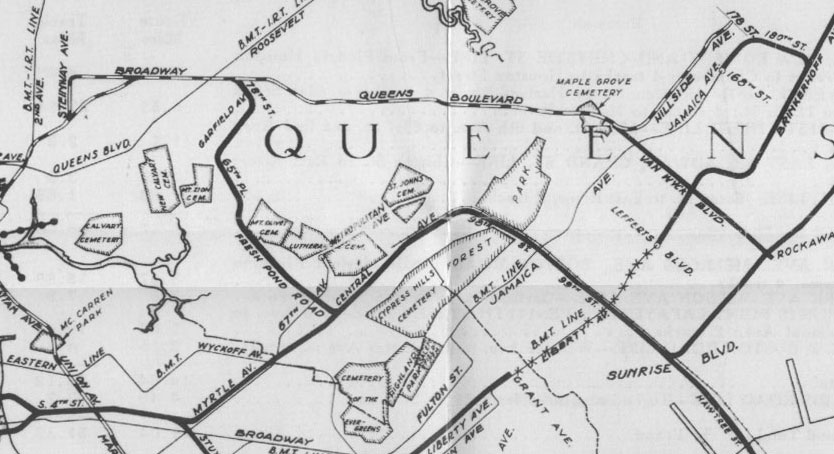

The LIRR Rockaway branch was built through the heart of southern Queens to speed rail travel from Long Island City to the Rockaways back when they were a huge summer destination on the scale of Coney Island or Atlantic City. When the subways were being built in the first half of the 20th century planners saw the need to capture this right-of-way and integrate it into the subway system. The IND Queens Boulevard subway has not one but two separate sections built so that any number of extensions to the Rockaways could be built. At Roosevelt Ave station there is an abandoned terminal section which even had tiles installed for a line out to the Rockaways and between 63rd Dr and 67th Ave stations there are two bell mouth portals in the walls of the tunnel to allow for connections to a line to the Rockaways.

The line itself branched off the LIRR Main Line after Rego Park and ran south through Forest Park to Woodhaven and Ozone Park where it island hopped through Jamaica Bay to the Rockaways. In 1956 the city finally converted the southern section from Ozone Park to the Rockaways to subway service, cutting off the northern section which was left to rot. At the same time Idlewild Airport was opened as well as new Robert Moses built highways to connect the airport to the city. The Rockaway branch was left to rot while the people of the Rockaways had their commutes increased as their once quick ride into midtown was increased by a more roundabout route through downtown Brooklyn and lower Manhattan.

Today as the population of the city and number of travelers entering New York through JFK Airport both grows the need for improved transit in the outer boroughs becomes paramount. New York has now surpassed the last population peak following World War II and shows no signs of stopping. The only answer, as it was then, is to grow in the boroughs. Land prices have increased not only in Manhattan but in the areas of Brooklyn and Queens closest to Manhattan. Middle class residents will be pushed further and further out and while some sections of the city have the transit to serve them others are being left behind due to neglect.

Right now the only way into Manhattan from southern Queens via transit is by subways which only run through Brooklyn first or by the more expensive LIRR at Jamaica. This leaves thousands of residents and travelers from JFK with a 40+ minute commute just to get to lower Manhattan, not to mention further when you consider many of these commuters would work uptown, the Bronx, or in northern Queens.

While one might characterize much of Woodhaven and Ozone Park as suburban compared to Manhattan they are still dense urban areas that have little park space themselves. While there are large parks such as Forest Park or Spring Creek Park those aren’t exactly a park you are going to stroll down to with your kids unless you happen to live a few blocks away. And even then there aren’t many facilities to be had when you arrive. So to say this section of the city is in need of better recreational facilities isn’t a stretch.

The QueensWay project aims to take the northern section of the Rockaway Branch from Rego Park to Ozone Park and make a High Line out of it. From Rego Park to Woodhaven the line runs through mostly wooded parks as it is so this would add a commuter trail along existing facilities. But from Woodhaven to Ozone Park the line is an elevated railroad running through the air like the High Line. There would be new open space for residents, so they claim. Like with the Low Line the QueensWay would create a “park†that isn’t really a park. The elevated line through Ozone Park is at most 60ft wide, hardly enough to have a soccer field. A trail style park like the High Line would be … not like the High Line at all since we are looking at something about twice as long and without any of the population to support it. Proponents of the QueensWay show a landscaped ribbon park with community centers and retail. As I said before Ozone Park is not Chelsea. The High Line already can’t pay for itself and it’s one of the most visited landmarks in the city. The QueensWay would end up being a fraction of any fanciful designs they are proposing out of purely sustainability factors.

And at the end of the day what would serve the city better: a park or a new transit line? The transit needs of southern Queens are obvious. A branch of the subway or even the LIRR would cut travel times dramatically and make access to JFK significantly easier for millions of travelers. Proponents of the QueensWay would argue that why should they allow a train line to be built through their backyards only to help commuters and tourists that won’t even spend money there while a park would directly serve the community?

If you built a park the city would be making the same zero sum mistakes as it’s made time and time again. A park is very hard to get rid of. A train line would open the area not just for commuters but for locals too. It would connect many of the large parks in Queens along the railroad so that parks that were once far away would now be a quick 5 minute subway ride away. Not only that but improved public transit to these undeserved sections of the city would improve air quality by reducing taxi trips out to the airport and car trips to and from the city. This would combine the need for better park access with improved transportation.

What ultimately worries me is that we are falling into the same trend of New is Always Better. We no longer invest in infrastructure in the country at the levels we desperately need. Right now we have a golden opportunity, a blessing in disguise because we’ve let these sections of infrastructure fall apart. While it would have been ideal to keep them in service we still can save them and control growth more effectively. But I worry that we are still stuck on the failed idea that one great idea can save us. People think the High Line is the silver bullet but in reality it was one part of a complex puzzle. Places that aren’t as fortunate to have the economic vitality as Manhattan still see the silver bullet as the only answer. How many forgotten civic centers or disused stadiums dot the landscape? It was Urban Renewal in the 1950s and 60s, downtown malls in the 1970s and 80s. Now it will be ripping up precious infrastructure to hopefully drive the High Line Effect.

We can’t afford to keep taking our valuables and selling them off to the highest bidder to just to get a flashy new toy every generation. That also isn’t to say there aren’t many deserving proposals out there where a new park or development would be the best way to go. We just need to know where the line is and not be pulled over to one side by smoke and mirrors (or rather, unproven economic growth and fiber optic light pods).

RT @vanshnook: The High Line Effect: Thoughts on Reusing Infrastructure http://t.co/6pppEgbHB0

Mike Russo liked this on Facebook.

Teddy Montee liked this on Facebook.

James P. Shaw liked this on Facebook.

Daniel Rogers liked this on Facebook.

RT @vanshnook: The High Line Effect: Thoughts on Reusing Infrastructure http://t.co/6pppEgbHB0

Sally Foster liked this on Facebook.

Kate Farrish liked this on Facebook.