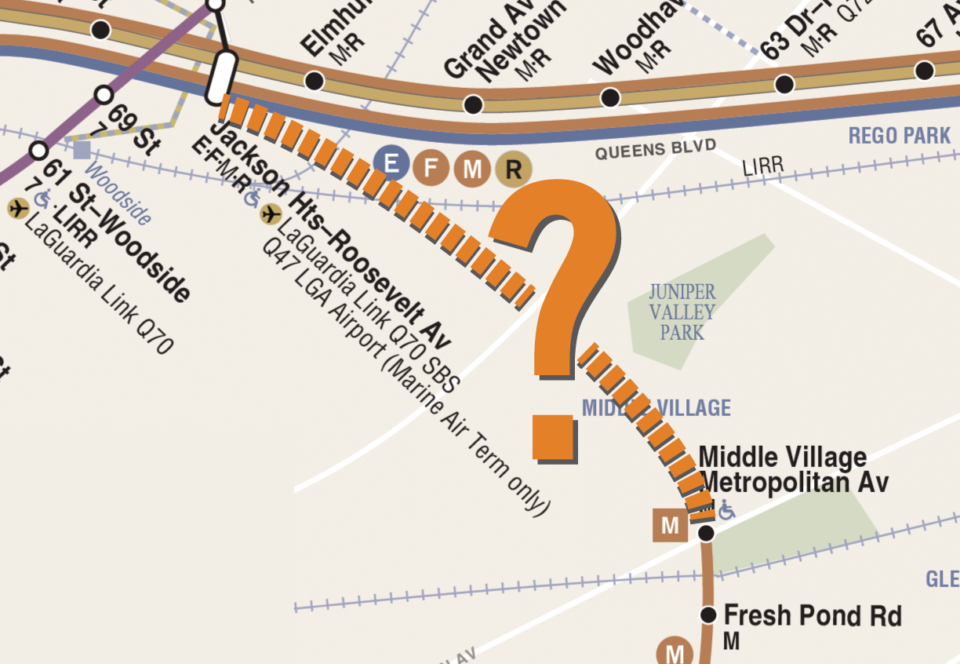

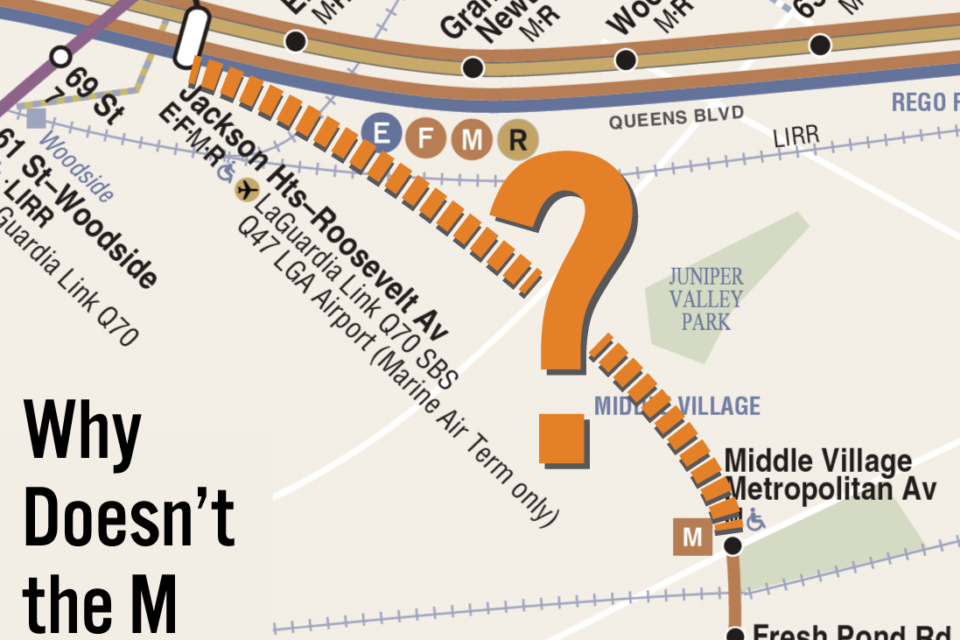

In my efforts to build community support for the QueensLink, I find myself talking to people about extending the M train. Since the M loops back into Queens, some folks thought that we were planning on extending it from its Middle Village end, not from Queens Blvd. Once people realize this, the inevitable next question I get is, “Why doesn’t the M train loop up to Roosevelt Ave to make a loop?”

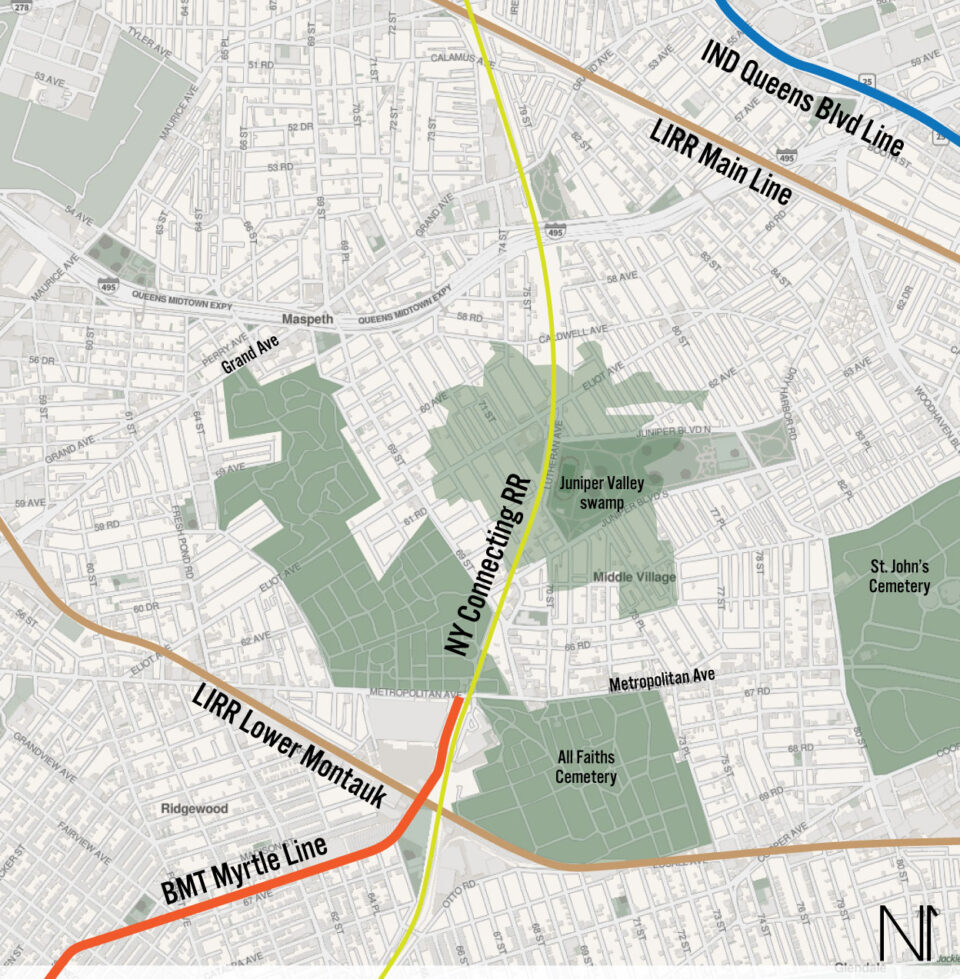

It doesn’t take a rail fan or subway foamer to see how close this connection is. The M train has always been a bit of an oddity, ending its run seemingly in the middle of nowhere. While Middle Village is very much in the middle of Queens, the neighborhood is a relatively sleepy low density suburb, surrounded on two sides by cemeteries (which are even sleepier). But just north of here is Queens Blvd, and the very busy neighborhoods of Woodside, Elmhurst, and Jackson Heights. Not to mention, there is an existing rail line cutting through the center of them all.

History

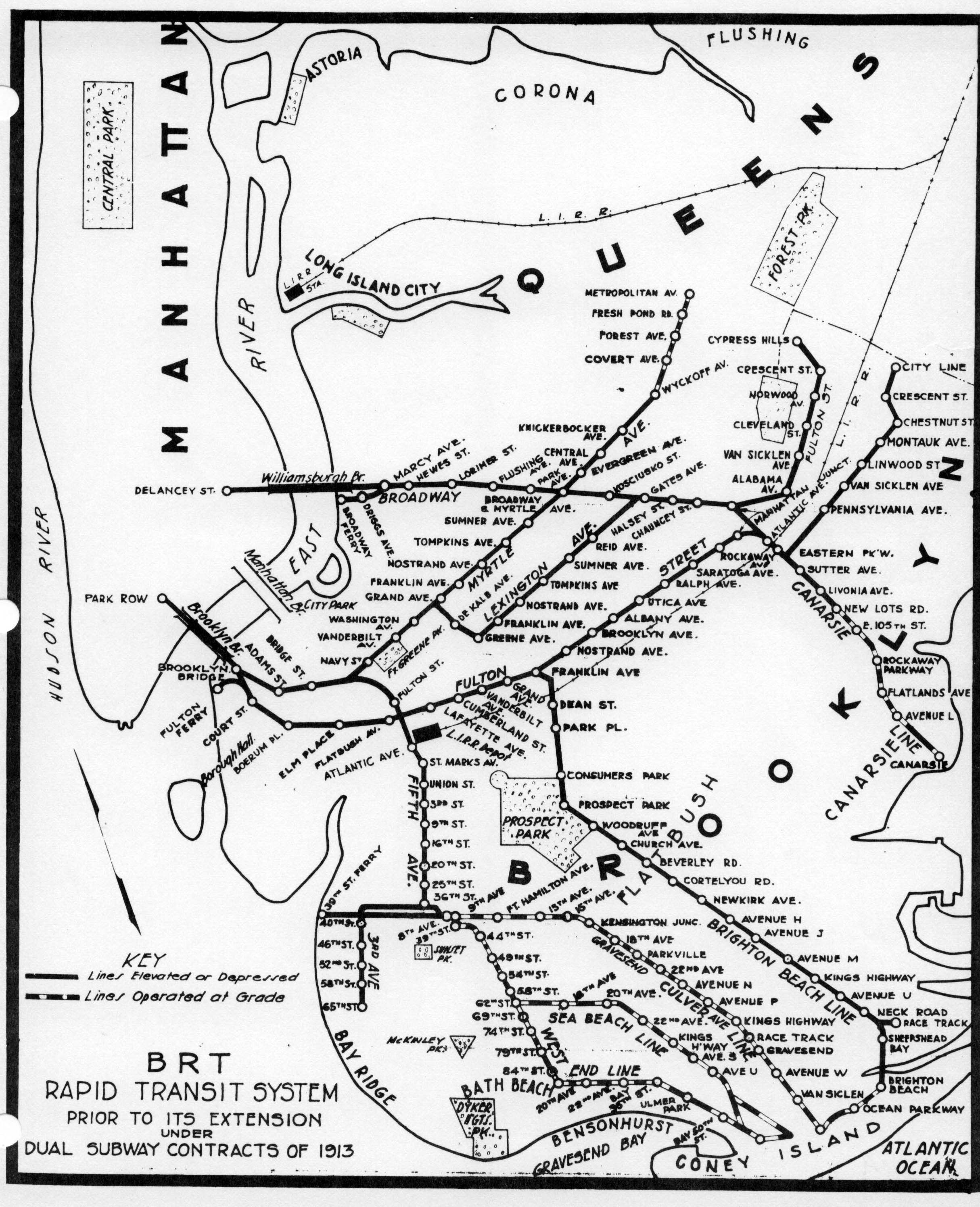

What we know of today as the M train began running in 1889 as the Brooklyn Elevated Railroad, running from Sands St in Downtown Brooklyn to Broadway along Myrtle Ave. This was quickly extended from Broadway to Wyckoff Ave, at the border between Kings (Brooklyn) and Queens Counties. In 1898, a track connection was made to the Brooklyn Bridge, extending trains to City Hall at the Park Row terminal.

The Wyckoff Ave terminal was a major transfer point for trolleys in Brooklyn and Queens. Initially, there was also a steam dummy line which also ran from Wyckoff Ave out to Lutheran Cemetery, on the other side of Ridgewood. This line was first connected to the el tracks via a ramp in 1906, so that el trains could continue to the cemetery, at Metropolitan Ave.

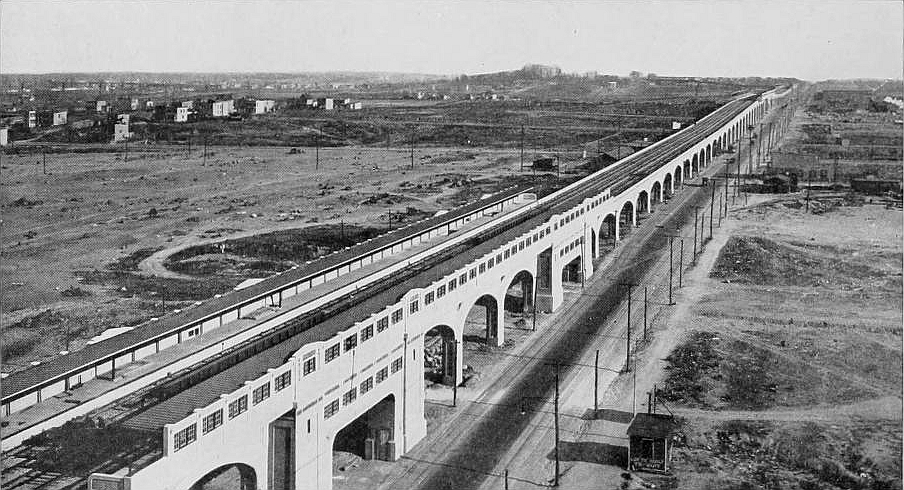

After the success of the first subway in Manhattan, the Brooklyn Rapid Transit Co. (BRT), which operated the Myrtle Ave Line, wanted to connect its elevated lines with new subways in Manhattan. As part of their contract with the city (known as the Dual Contracts), the BRT was given the right to elevate their tracks between Wyckoff Ave and Metropolitan Ave, as well as built a track connection between the Myrtle Ave and Broadway elevated lines. Previously, riders would have to transfer between the upper level (which sits abandoned today) and lower level.

As part of the Dual Contracts, the section of elevated track between Broadway and Metropolitan Ave was reinforced to support the larger, heavier subway cars. Elevated cars were often built of wood, and required less power due to their lower weight. Subway cars were made of steel, and needed more power. The older section of track, from the Brooklyn Bridge to Broadway, would have been upgraded had a proposed subway-bridge connection at Chambers St been built. But since this plan was scrapped, the older track structure was allowed to deteriorate until 1969, when the MTA moved to demolish this line. Service had been cut back to Jay St when the elevated train tracks on the Brooklyn Bridge were removed, and ridership had slowly declined as the Navy Yard was slowly mothballed after World War 2.

Until 2010, the M train ran to Chambers St in Lower Manhattan. The M shared the same brown colored bullet that the J and Z trains use. At various times, the M would also be extended back into Brooklyn via the Montague St Tunnel, serving various lines to southern Brooklyn. Most recently, the M had been extended at rush hour along 4th Ave and the West End Line (D train) to Bay Parkway.

Like so many New Yorkers, the M was forced to relocate due to economic conditions. Back in 1968, as part of the Chrystie St Connection, the tracks west of Essex St station were connected to a new tunnel that linked up to the 6th Ave local tracks at Broadway-Lafayette St station. This connection was served by a new KK train, which initially operated between 168th St-Jamaica Center and 57th St-6th Ave. But budget cuts and declining ridership led to the KK train being cut back, and by 1977, eliminated entirely.

In 2001, at the other end of town, the 63rd St Tunnel (which had been built in fits and starts since 1969) was finally connected to the Queens Blvd Line in Long Island City. This connection allowed 50% more service between Queens and Manhattan, and required the creation of a new subway line. The V train was selected to run between Forest Hills and 2nd Ave-Lower East Side via 6th Ave during the day. But like the KK before it, budget cuts soon threatened this service.

To save on operating costs, the MTA chose to combine the M and the V using the Chrystie St Connection. Initially, the MTA wanted to eliminate the M designation, replacing it with the V in Bushwick and Ridgewood. But the M had been around much longer than the V, and the swap was unpopular. The M, therefore, was rerouted from Lower Manhattan to Midtown, and back out to Queens.

The Left Overs

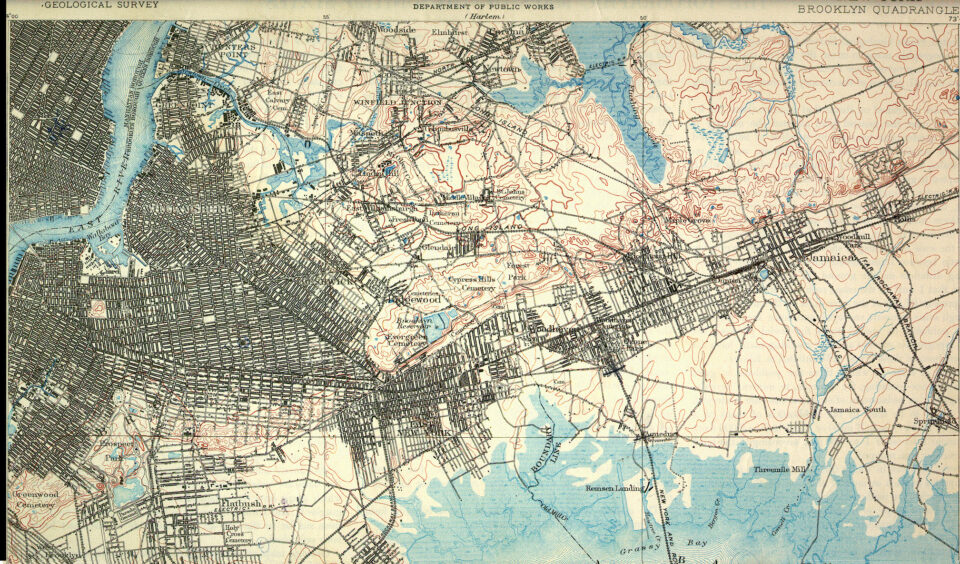

To understand why the M was never extended north, we must understand the land. Long Island is a glacial moraine, created when glaciers repeatedly rocked against the landscape and scraped all manner of dirt and rock, depositing them at their mouths until land built up. This build up as glacial debris can be seen in the form of the backbone of hills which runs down the center of Long Island. South of the moraine, the land is low and flat as it approaches sandy beaches along the Atlantic Ocean. North of the moraine, the land is hilly and uneven, with jagged peninsulas lined by rocky beaches stretching into Long Island Sound.

Between Downtown Brooklyn and Ridgewood, Myrtle Ave was relatively flat and easy to develop. After Ridgewood, the M train tracks runs right up to the moraine. Going further would be more difficult, though not necessarily from an engineering point of view, as the New York Connecting Railroad was able to cut an elegant path through these hills. But these hills made real estate development harder. This made the land cheaper, and more ideal for building a freight rail line through.

Until 1898, Brooklyn was an entirely separate city from Queens. A transit company would therefore need to get a separate operating charter from the state if they wanted to operate between counties. This was made all the easier when the City of New York consumed the City of Brooklyn and County of Queens to create the City of Greater New York that we know today.

Prior to this, the trolley and elevated lines ran right up to the border. This is still reflected in our modern bus lines, which often use Ridgewood as a terminal or transfer point. In the 1880s and 90s most of the industry was concentrated in Lower Manhattan, downtown Brooklyn, and Williamsburg. New streetcar and elevated lines allowed workers a way out of the cramped, dangerously overcrowded tenements that were located in these same industrial areas. Soon, older farms were being ripped up and converted into middle class neighborhoods with names we recognize today: Bedford, Stuyvesant, Bushwick, and Ridgewood.

The relatively flat land and robust transit were ideal places for dense housing. Higher up on the hills between Queens and Brooklyn, where land was harder to develop, a longer term form of housing was developed. With the population of both New York and Brooklyn exploding in the second half of the 19th Century, the cities realized that they needed somewhere to keep their former citizens. The cheap land in the hills became the perfect place for cemeteries.

Today, central Queens is home to some of the largest cemeteries in the city, including Calvary, Mt Zion, All Faiths (formerly Lutheran), St John’s, Evergreens, Most Holy Trinity, Mt Judah, Union Field, Mount Carmel, Mount Neboh, Mount Lebanon, Cypress Hills, and other smaller ones. While the phase “the dead don’t ride the subway” has often been said in response to why the M doesn’t travel deeper into Queens, the truth is that the M was first extended, back in 1906, to serve these very cemeteries. People still had to get to the cemetery to bury their loved ones, and cemeteries acted as park space for the cramped city.

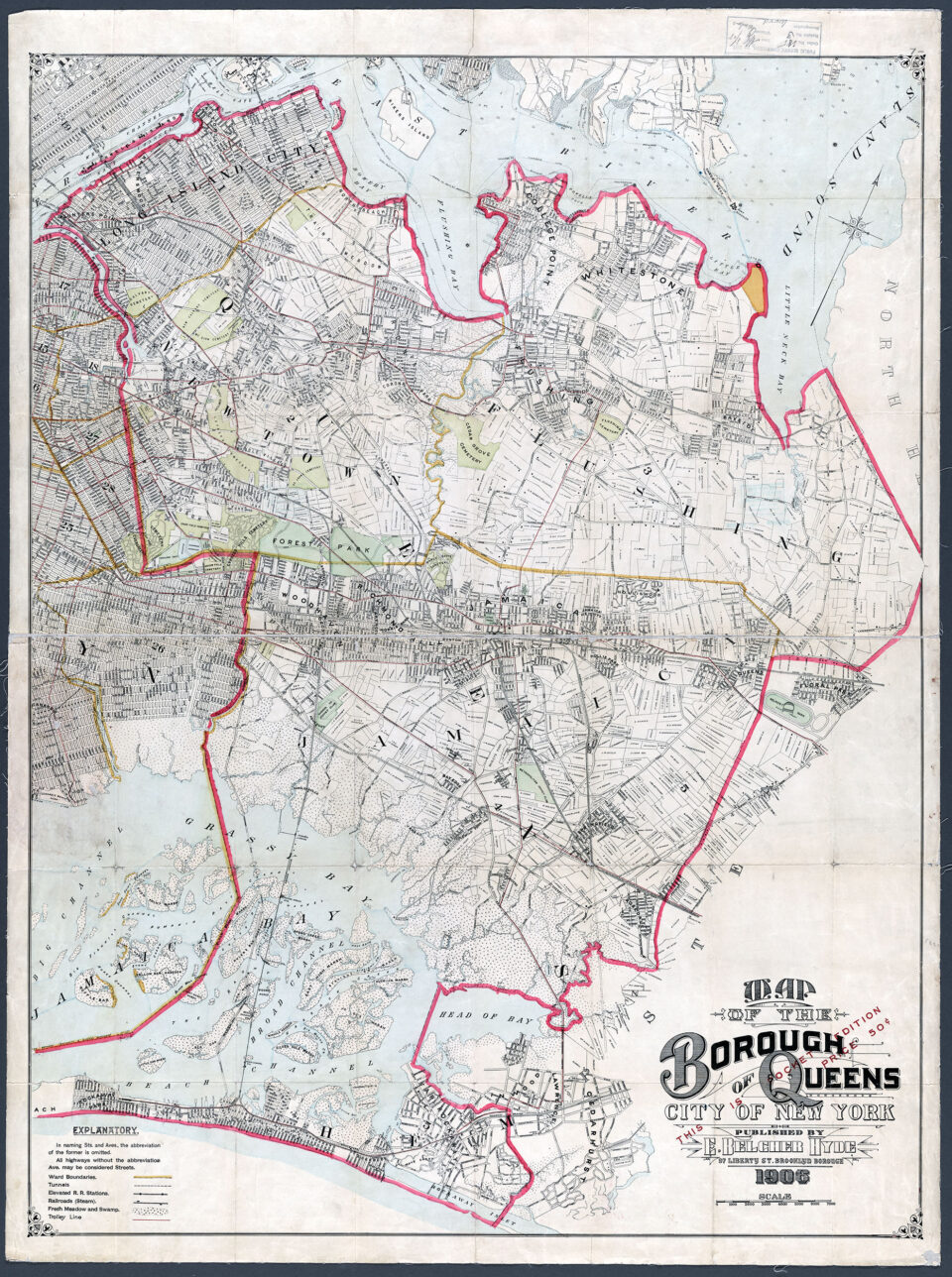

The former towns of Newtown, Flushing, and Jamaica that came together to create Queens were very much that, small towns. Jamaica had developed more because of the Long Island Railroad. Flushing was vying to be the next great port city, but was too remote to be a real contender. Newtown had no center, and instead was better known by the smaller settlements that grew up around unpaved highways or LIRR stations: Woodside, Elmhurst, and Corona.

Queens was persuaded to join New York City by the promise of infrastructure; New train lines, water mains, sewers, roads, bridges and highways. In 1901, plans for the first of these projects, the Queensboro Bridge, were finalized. The new bridge would also carry streetcar and elevated train tracks. After it opened in 1909, Long Island City exploded. New development was limited by lack of existing paved roads and sewers (something that the former corrupt political bosses of Long Island City had used to enrich themselves instead of building), so these were often left to private developers.

This is one of the main differences between Manhattan and Brooklyn, and Queens. The streets in the older cities had been planned and surveyed before development came in. Queens never had the luxury of such foresight and planning, which is why the borough has such a mess of street grids. Development radiated from the Queensboro Bridge, and soon crystallized along the two new elevated subway lines that opened as part of the Dual Contracts. The Astoria Line (today, N, W trains) served the spine of the old Long Island City, while the new Corona Line (7 train) ran eastward into the farmlands between LIC and Flushing. This was the catalyst for the creation of Jackson Heights.

It wasn’t only subways which brought development. Prior to 1910, all Long Island Railroad trains ended their journeys at the edge of the East River. Riders would transfer to ferries to continue their journey to Manhattan. In that year, the Pennsylvania Railroad (which owned the LIRR), opened the East River Tubes between Pennsylvania Station and Long Island, and for the first time since the last ice age, connected Long Island to the mainland of North America.

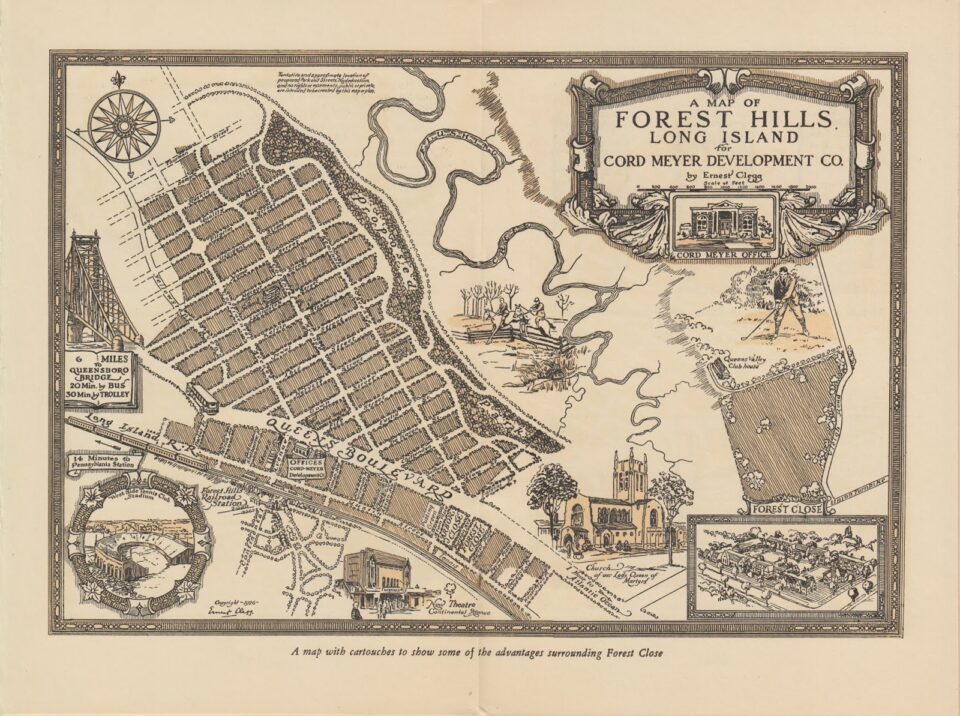

The LIRR had consolidated smaller railroads, and expanded its Main Line through Woodside to Jamaica. The new 4 and 6-track main line featured express and local stations between Penn Station and Jamaica. While streetcars and subways were driving middle class housing development, the higher priced LIRR spurred on housing for the well-to-do. This included new neighborhoods designed in the new Garden City model, with more open space and large single family housing, and names like Rego Park, Forest Hills, and Kew Gardens.

Notably, these improvements and developments were being built further north of the hilly inland terrain sandwiched between Brooklyn and Queens. That isn’t to say that there wasn’t transit in central Queens. One of the many smaller railroads that had been consumed by the LIRR, the South Side Railroad, had built its main line along Newtown Creek, through Ridgewood, Glendale, and Jamaica, before turning south and running out to Babylon and Patchogue. Today, the section of track west of Jamaica is used by the LIRR Babylon Line. Due to the slow, windy nature of the route through Queens, the LIRR opted to upgrade and connect its Main Line to Manhattan, leaving the older line, today known as the Lower Montauk Branch, with less service and no direct service into Manhattan. Passenger service here limped along until 1998. Today, the line is active with freight.

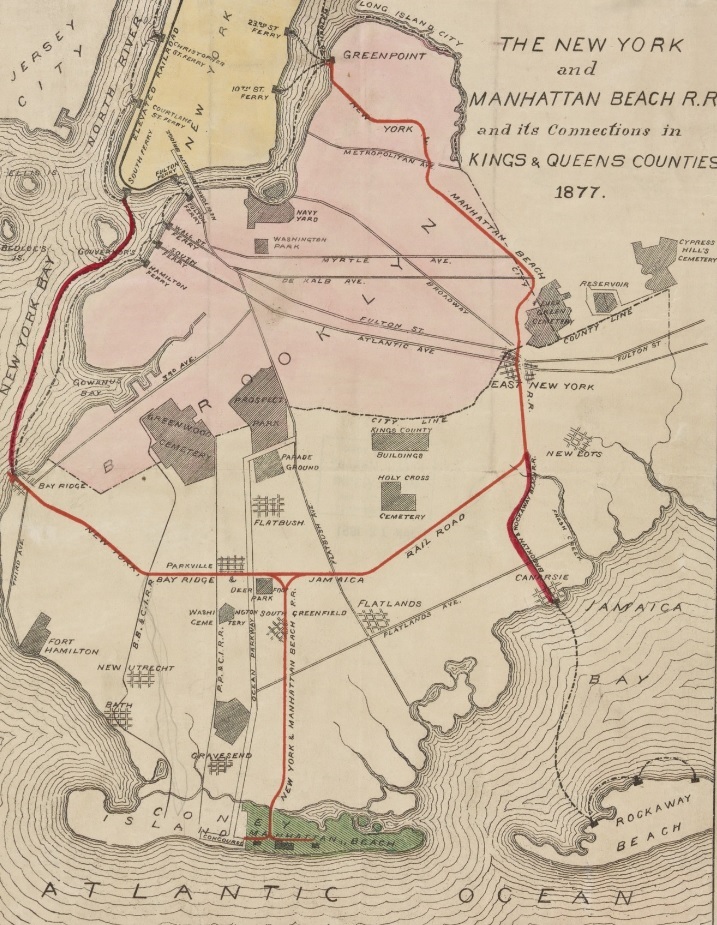

When the Pennsylvania Railroad set out to finally connect Manhattan Island with the mainland, it did so on two fronts. The North River Tubes connected to New Jersey to the west. To the east, the East River Tubes connected to both Long Island and New England via a new bridge, the Hell Gate. Due to freight trains been virtually banned from Penn Stations (first steam, then diesel), the Pennsylvania RR opted to build out a new freight terminal in Sunset Park, Brooklyn, and use an old LIRR line to act as a bypass around the city, linking up with the Hell Gate Bridge.

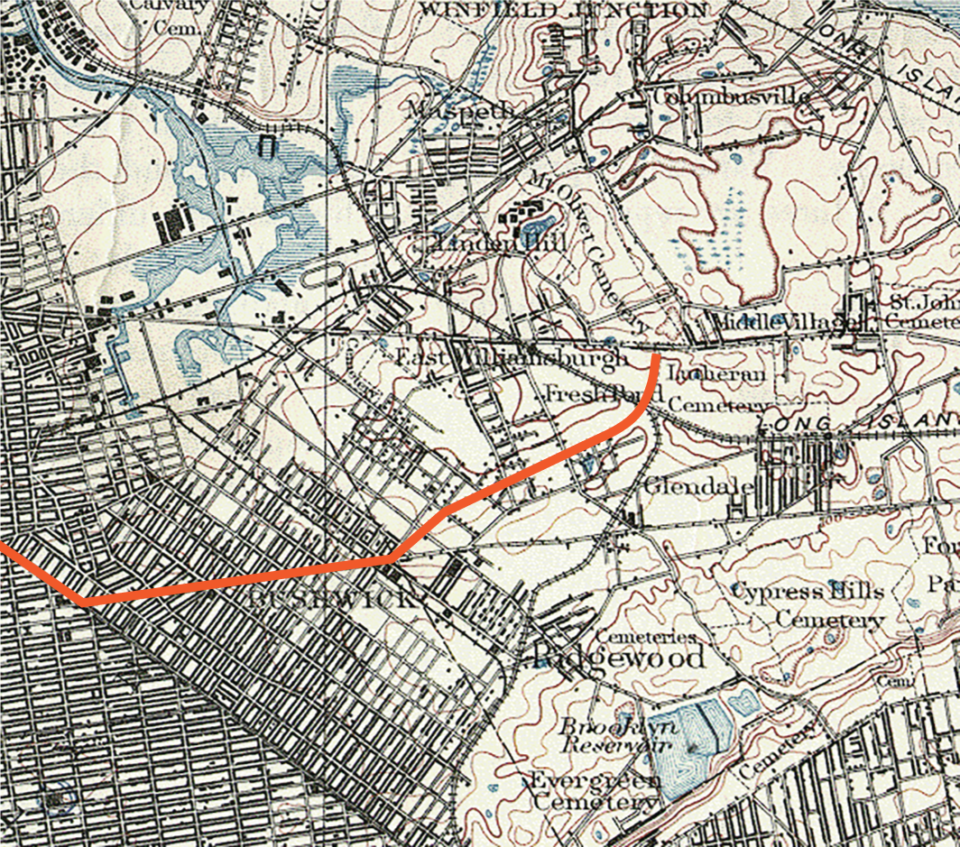

The LIRR Bay Ridge Branch had first been built, like all rail lines in southern Brooklyn, to get riders to Coney Island. The railroad ran ferries from New York to Bay Ridge, where riders would transfer and take the train to the beach. The Bay Ridge Branch ran east to west, where it met up with the former Manhattan Beach Railway, that once ran from LIC to Manhattan Beach via East New York. By combining both railroads, the LIRR created a belt line. This belt line was directly linked up to the Lower Montauk Branch at Fresh Pond.

The new rail link between Fresh Pond and the Hell Gate Bridge was called the New York Connecting Railroad. Freight from New Jersey would be floated across New York Bay by barge, then loaded onto trains and run up through Queens and over the Hell Gate Bridge. This service is still operated today, and is slated to see more freight as the Port Authority tries to reduce truck traffic on local roads. Passenger rail service was operated on the older LIRR Bay Ridge and Manhattan Beach Lines, but not along the New York Connecting Railroad. While the M train terminated directly adjacent to the new rail line, there was no other passenger rail service in this location.

Much of the LIRR had been built along city streets or at grade as it crossed them. The state had mandated that the LIRR eliminate these crossing for safety. In doing so, the railroad took on massive debt. By the 1920s, the LIRR was losing ridership to the new, cheaper subways. The LIRR had contracted with the private transit companies for joint service before World War 1, running their trains into Manhattan via BRT lines. When the US Government nationalized the railroads for the war effort, the subway companies were able to get out of this by claiming they were not freight railroads. This legal distinction barred the LIRR from sharing tracks with subway lines, requiring them to run their own, more expensive service.

By 1924, the LIRR closed many of its local stops in Queens. Local stops that had larger developments, like Rego Park, Forest Hills and Kew Gardens remained open. But smaller stops along the same line, at Grand St and Matawok (between Rego Park and Forest Hills) were closed. All service on the Bay Ridge Branch was eliminated.

The Marsh and the Mobster

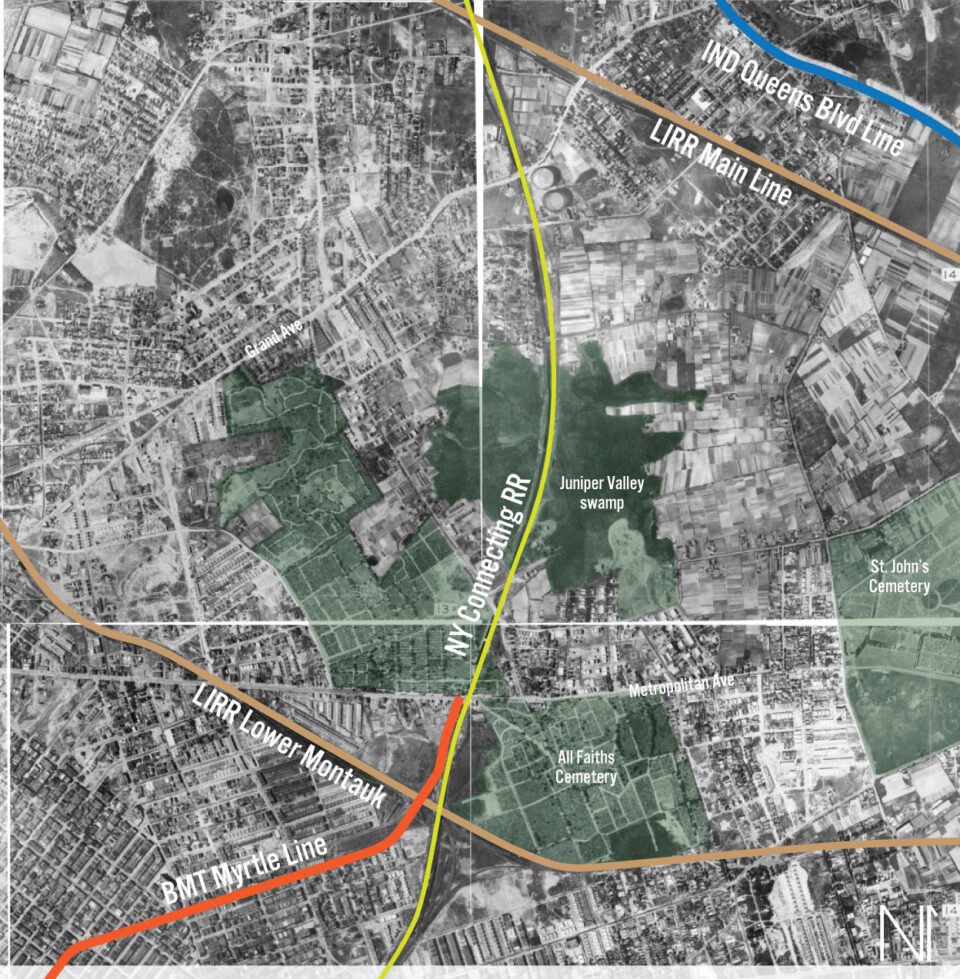

To understand why a large area of land, bisected by a rail line and sandwiched by two others, was not prime real estate, we must strip away the city that now exists and see what was there before. Until the early 20th Century, what is now Middle Village was a high plateau basin. While the general elevation of the land was higher than the surrounding lands (leading to the southern side having a gentile, sloping “ridge”), the top of the plateau had an elevated lip around it. This created a swampy area with poor drainage.

The swamp had provided peat for fuel, giving it some value. But the poor drainage made any development more costly. Besides being hard to access at the higher elevation, the swamp would ultimately need to be drained and filled. Neither the city nor private developers were willing to pay for the new sewers when so many other areas of Queens were flat and available for development for much cheaper.

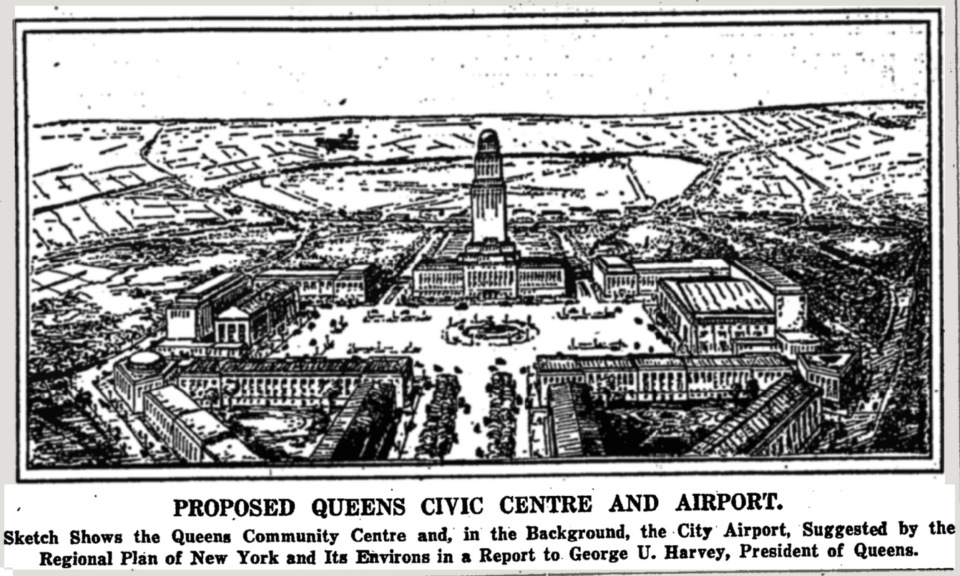

Being cheap and undesirable, the land was seen as the perfect opportunity to launder money. Arnold Rothstein, famed NYC gambler and gangster, acquired the land in the early 1920s, supposedly with his winnings from fixing the 1919 World Series. At the same time, the Federal government was looking for sites to build new airports in the NYC area. The high plateau in the center of Queens was selected as it offered better weather (less fog) than lower lying areas.

Rothstein knew his land could be worth more if there was already development on it, so he created a Potemkin Village of empty homes in an attempt to raise the property’s value. But before the land could be sold, Rothstein was gunned down in response to an unpaid gambling debt. The land was seized by the city for unpaid taxes. Because of the interest in an airport, as well as the stigma of being mob connected, few were willing to develop the land.

The Regional Plan Association proposed a large airport and convention center here in 1930. They saw the area having good rail and road access, especially once the new Queens-Midtown Tunnel opened. Even with this support, the Federal government chose Barren Island off Jamaica Bay, since it had already been filled and flattened for development, and was accessible by seaplanes. This became Floyd Bennett Field.

In 1937, the city turned the land over to the Parks Commissioner Robert Moses to create a new park, suitable for residential development. Moses, using Works Progress Administration money, began work on Juniper Valley Park. Developers were chosen to build homes on the eastern side of the park, away from the swamp. The swamp areas, with no other suitors, became a secret dump. In 1939, Sanitation Commissioner William Carey and Health Commissioner Dr. John Rice were indicted for dumping garbage into the swamp.

In 1940, the Queens-Midtown Tunnel was opened. While not directly accessible from Juniper Valley, road improvements along Borden Ave and Laurel Hill Blvd allowed new residents relatively quick access to the new tunnel. Though the western side of Juniper Valley Park took longer to develop, by the time the Long Island Expressway was extended through Maspeth and Middle Village in 1955, the land hand been fully covered by the homes.

That Time They Almost Built a Loop

At the same time that Arnold Rothstein was building a small empire through racketeering, the Mayor of New York City, John Hylan, was imagining his own dominion. By the early 1920s, the private transit companies were anything but loved. Due to post-War inflation, the five cent fare that was legally mandated was not enough to cover costs, and the companies began to cut service and defer maintenance.

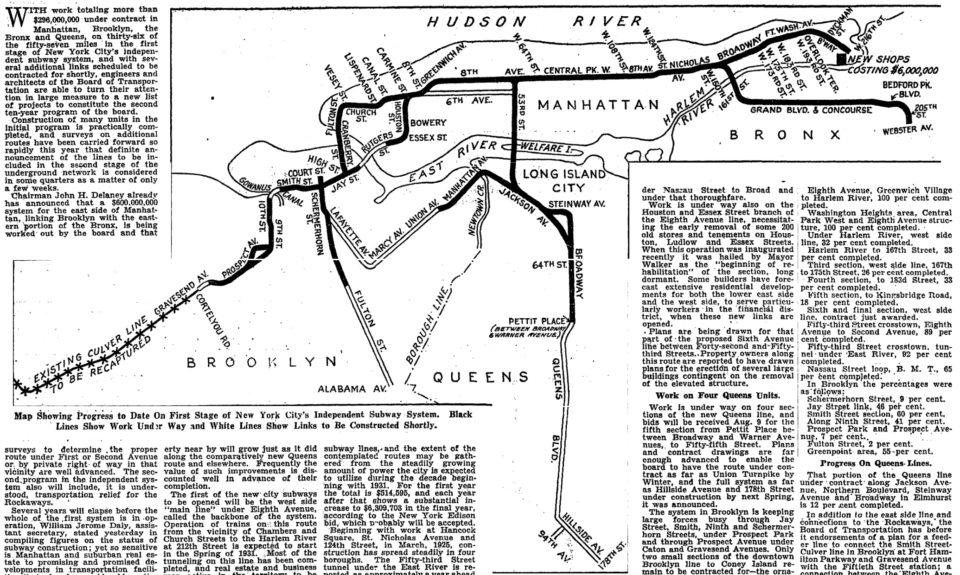

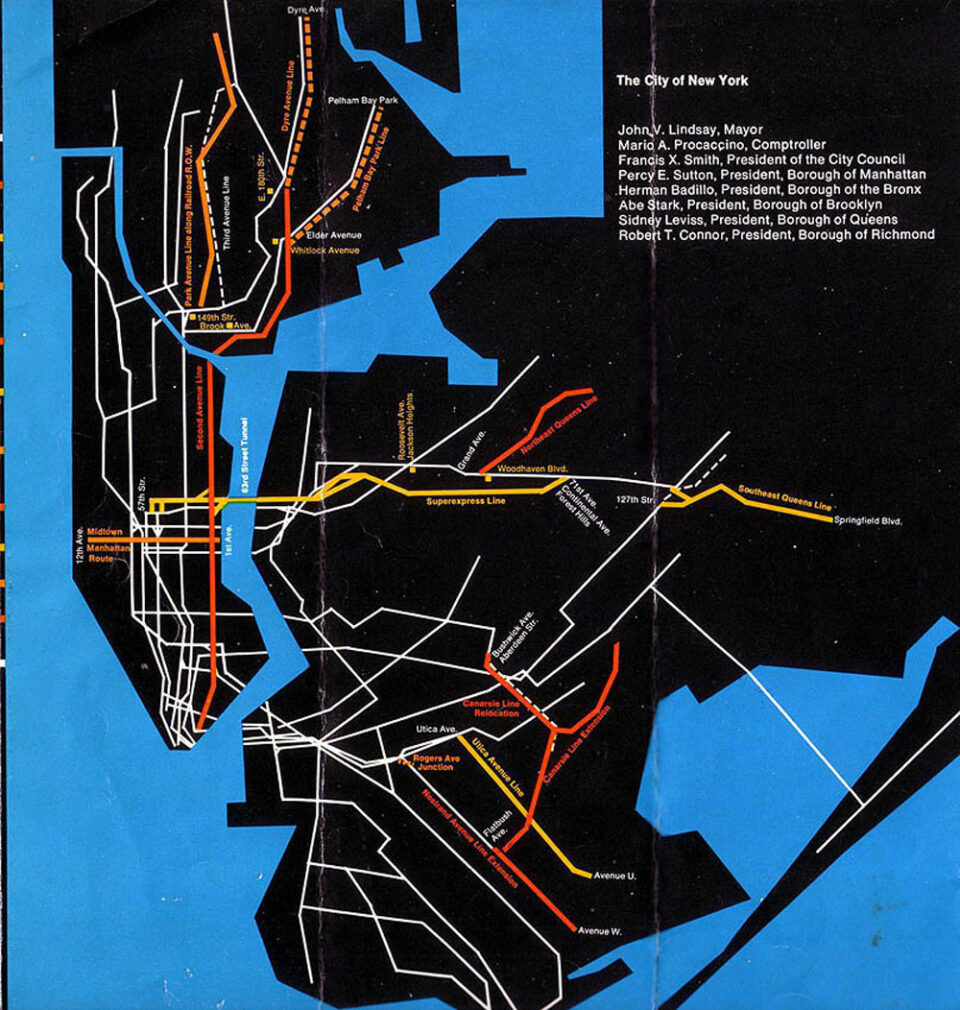

The mayor thought that the city should run the subways, and created a plan for a third subway system, the Independent City-Owned System (IND). Instead of extending existing lines, all new lines would be part of the city-owned system. While planners had initially drawn up new lines for Manhattan and Brooklyn, Queens was where the real growth was.

A new 4-track trunk line was devised for Queens as part of a larger improvement project for Queens. The new subway would be built underneath an extension of Queens Boulevard. Queens Blvd had initially been built alongside the Corona Line in Sunnyside, with a stately concrete viaduct down the center of the road. The extension would bring the highway all the way to Jamaica, connecting Jamaica to Manhattan via the Queensboro Bridge.

The IND was legally mandated to start making money after 3 years in operation. This meant that many parts of the new system had to be built in already developed areas, as it would take farms longer to redevelop. This led to a number of unique design choices for the IND. Today, you will notice two areas where the local tracks leave the express, forming a small loop, before linking back up with the express. In both Windsor Terrace and Astoria, the express tracks were built on a more direct path, so that express trains could run at higher speeds, while the locals would creep around tighter corners.

A third loop was initially proposed in Woodside, that would serve a neighborhood that is now almost lost to history: Winfield. Winfield is mostly known to railfans and the name of the junction point between the LIRR Main Line and Port Washington Branch. It’s name also lives on at St. Mary’s Winfield, a Catholic Church just off Queens Blvd. Winfield had developed around the LIRR, but lost service when the railroad ended its local service in 1924.

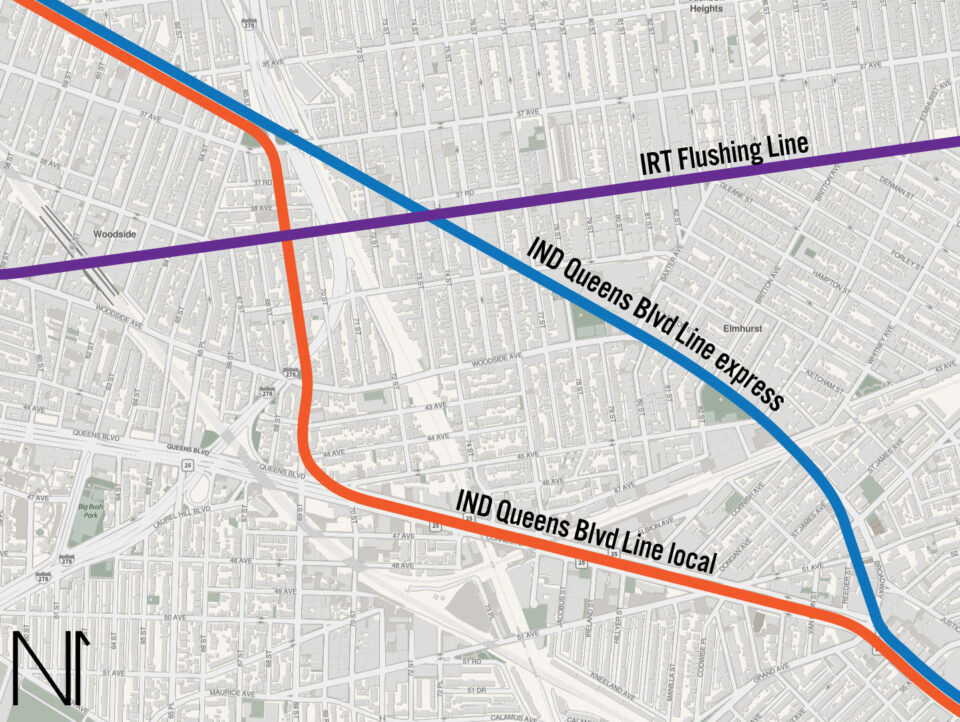

The loop worked like this: the 4-track trunk would run from Northern Blvd, along Broadway (as it does today). At 69th St (then known as Fisk Ave), the local tracks would turn south, while the express tracks would continue east-southeast along Broadway until they reached Queens Blvd. The local tracks would run along 69th St to Queens Blvd, where they would turn east, linking back up with the express tracks at Grand Ave. While no stations are proposed, it can be assumed that there would be local stations at Roosevelt Ave-69th St (connection to the 7 train), and along Queens Blvd near 72nd St.

Residents of Winfield demanded that the city include the loop as a replacement to the lost LIRR service. But members of the Board of Transportation balked at the idea, saying that it would remove the “rapid” from “rapid transit”. While the number of stations would have likely been the same today with the loop, the additional curves would have slowed down the local trains even more. As construction on the IND began, the real costs started to become apparent. The loop would have been more expensive to built, and the plan was cut.

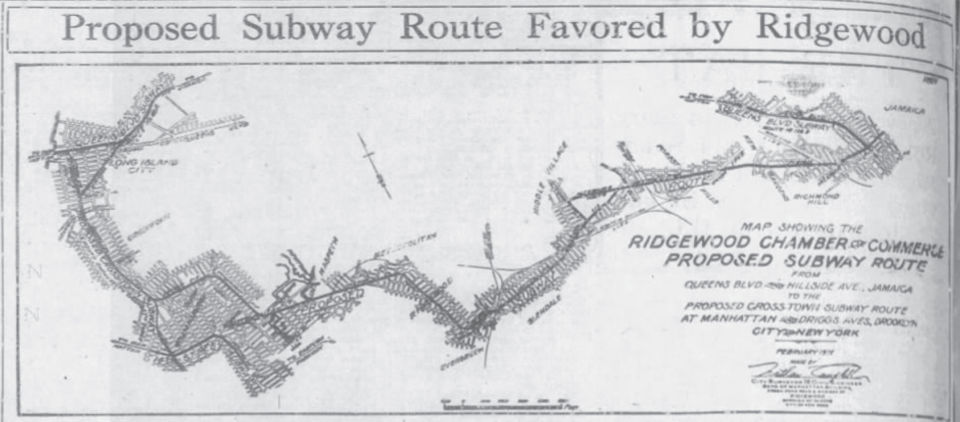

One of the aims of the IND was to replace the aging and much hated elevated train network. The main focus had been in Manhattan, but the IND had their eyes on the lines which served northern Brooklyn. Residents of Williamsburg, Bushwick, and Ridgewood already had relatively good transit coverage, but they too wanted to see the elevated lines replaced with subways. In 1928, the Ridgewood Chamber of Commerce published a plan for a new line that would have run from Greenpoint, through Maspeth, Ridgewood, Glendale, Forest Hills, and Richmond Hill before linking up with the new IND Hillside Ave Line.

The IND had focused the next round of expansion on the Utica Ave Line, running from the Lower East Side, through Williamsburg, Bed-Stuy, Crown Heights, and East Flatbush. Building off of this, planners added a second branch that would run along Myrtle Ave out to Glendale, then take over the LIRR Rockaway Beach Branch. A third element was a new branch of the Crosstown Line (G train) would be built along Lafayette Ave, linking up with the Myrtle-Rockaway Line.

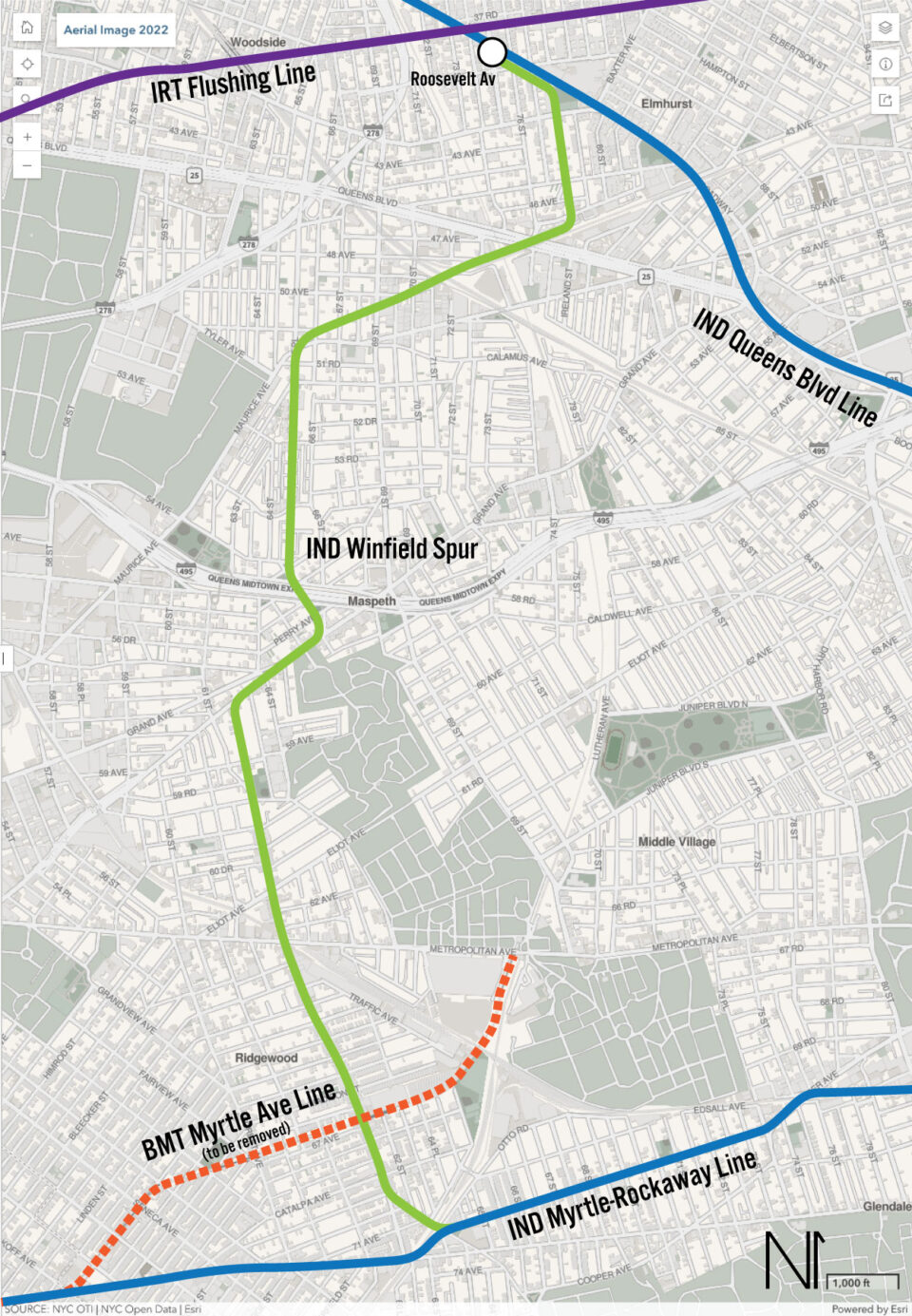

To build support for continued funding, planners developed a plan to connect the Queens Blvd Line with a new line running through Winfield and Maspeth. The Winfield Spur, as it became known, began at the Roosevelt Ave station. Here, a 2-track terminal would be built, while two more tracks would connect to the Queens Blvd Line local tracks. The line would turn down 78th St, turning southwest at the LIRR Port Washington Branch, and running alongside the LIRR until Garfield Ave. Here, the subway would come above ground, running elevated, south along 65th Pl to Grand Ave. The line would turn down Grand Ave and dive back underground before turning south under Fresh Pond Rd.

The line would run down Fresh Pond Rd until it met up with the Myrtle-Rockaway Line. There is little detail about the line from here, but it appears that the IND planned to turn the spur east, towards Rockaway, rather than have the line loop back to downtown Brooklyn. Had the line ever been built, it’s possible this would have changed, and the G today would have run in a giant loop through central Queens.

The IND released their ambitious plans, known today as the Second System, mere weeks before the stock market crash of 1929 that heralded the Great Depression. At this point, no sections of the IND were even close to being complete, and the cost overruns soon began to impact future plans. Quickly and quietly, the IND began to pare back its future plans, focusing on finishing what it had started. The first to get cut was the Myrtle-Rockaway Line and Winfield Spur. The Rockaway Line would be reconfigured to connect to the Queens Blvd Line further east, at 63rd Dr, and also connect with the Fulton St Line in Ozone Park.

It’s worth pointing out that the IND didn’t fully give up on the Winfield Spur. The IND incorporated a number of unfinished provisions along their lines for future extensions. Many of these were contracted well before the future lines were cut, so it seems strange to have these abandoned parts knowing that they would never be used. A 2-track terminal for the Winfield Spur was actually built at Roosevelt Ave station (with tiles installed!), and all four trackways exist (no tracks were ever installed.) More well known is the middle track at Bedford-Nostrand Avs station on the G train, with dual tail tracks extending east under Lafayette Ave for another block.

It can also be supposed that the IND never really intended on building the Winfield Spur, or if it did, would have chosen a more direct route. The route of the Winfield Spur is far more convoluted than a typical IND line, owing much to the geographic difficulties of the area, and aim to serve as much of the existing neighborhoods as possible.

Once the Depression hit, all talk of building a subway through central Queens died. In 1933, the first leg of the Queens Blvd Line opened to Roosevelt Ave. This station is only a half mile from the neighborhood of Winfield (though, admittedly, it is still hard to access due to the crisscrossing of LIRR tracks.) A station at Grand Ave and Queens Blvd, opened 3 years later, which was accessible by bus. But mostly, by the end of the 1930s, it was clear that residents were switching to cars.

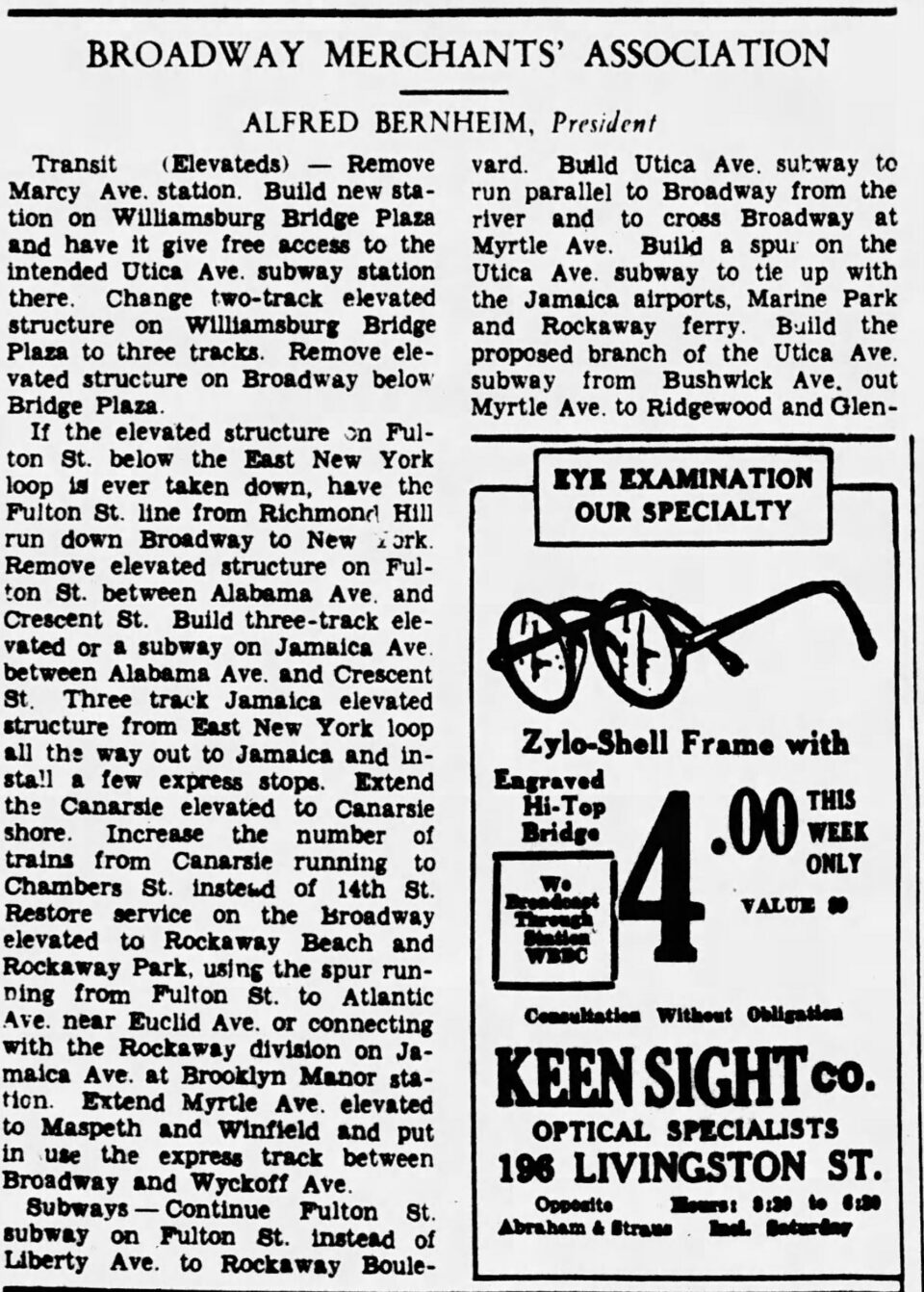

In 1931, Alfred Bernheim, president of the Broadway (Brooklyn) Merchants’ Association, proposed extending the M north into Winfield. As far as I can tell, this is the only published proposal to extend the M, specifically, northwards. This was never official, and at the time many groups and individuals would post their ideas in local papers.

Missed Connections

In 1940, the bankrupt private IRT and BMT were sold to the City, which consolidated all three companies under the Board of Transportation. Years of deferred maintenance, as well as the beginning of the post-War automobile culture, left the city holding the bag in terms of ballooning maintenance costs.

The city struggled to expand the subways, finally turning things over to the new Transit Authority in 1953. The TA was able to float bonds to pay for new projects, the largest being the conversion of the LIRR Rockaway Branch into the Rockaway Line (A train). When the Federal Government passed the Federal-Aid Highway Act, paying 90 cents for every dollar of highway, all was lost for subway expansions. By the time that planners realized that expressways were not the solution that all had believed, it was too late. Despite this, ridership in Queens was still very high, due to the density of development and limited number of rail lines. Plans were drawn up for new lines, but extending the M north was never in the cards.

It could be argued that in the 1930s there may have been enough demand for an extension of the M train. At the time, the M train reached both the Financial District and Downtown Brooklyn. But, technically, so did the new IND. The G train originally ran all the way to Forest Hills, and provided direct or indirect (transfer) access to these same places. Ridership between Brooklyn and Queens turned out to be a small fraction of the overall demand, overwhelming express trains as riders dismissed the G. Focus quickly shifted to providing more service between Midtown and Queens, with the TA and MTA building two new tunnels connecting to Manhattan over the next half century.

A very real possibility is that planners simply didn’t want to funnel more people through Roosevelt Ave. Roosevelt Ave station, being a major transfer point for both express and 7 train riders, is one of the most congested stations in the subway network. Riders would literally delay trains as they run to swtich between local and express. The proposed super-express subway bypass was designed as a way to reroute express riders around the station. Had the M train been extended north to Roosevelt Ave, there was a very real possibility that the additional ridership would overload the station.

After the war, many of the neighborhoods that the old Myrtle Ave El served quickly deteriorated, due to old age and disinvestment. Many residents opted to move out to the new suburbs, where homes were brand new and had more space. Once middle class and working class sections turned into slums for newly arrived immigrants; blacks from the deep south and Puerto Ricans. Red lining had limited investment in these neighborhoods, and ridership began to drop as residents moved out.

Racism played a large part in this migration. Even today, Maspeth and Middle Village are far whiter and more conservative than its neighbors to the south. Extending a subway that ran through neighborhoods full of poor minorities would have been fought, had the TA even had the money to dream of such an extension. That isn’t to say that conservatives are inherently anti-transit. QueensLink has found a lot of support in “red” areas of the city because people understand that improving transit also means improving property values.

Today, the bus lines which run through the heart of Queens are often so convoluted that they likely dissuade through travel. Due to the geography, there are relatively few straight north-south roads through central Queens. 69th St is one of the few, and could easily support a crosstown bus line between the end of the M and 7 train in Woodside. Yet this bus does not exist, and instead snakes its way through Maspeth and Sunnyside to LIC. Similar bus routes make awkward jaunts through Middle Village on their way to Queens Blvd. During the day, car traffic makes these runs far longer than they need to be.

Are We There Yet?

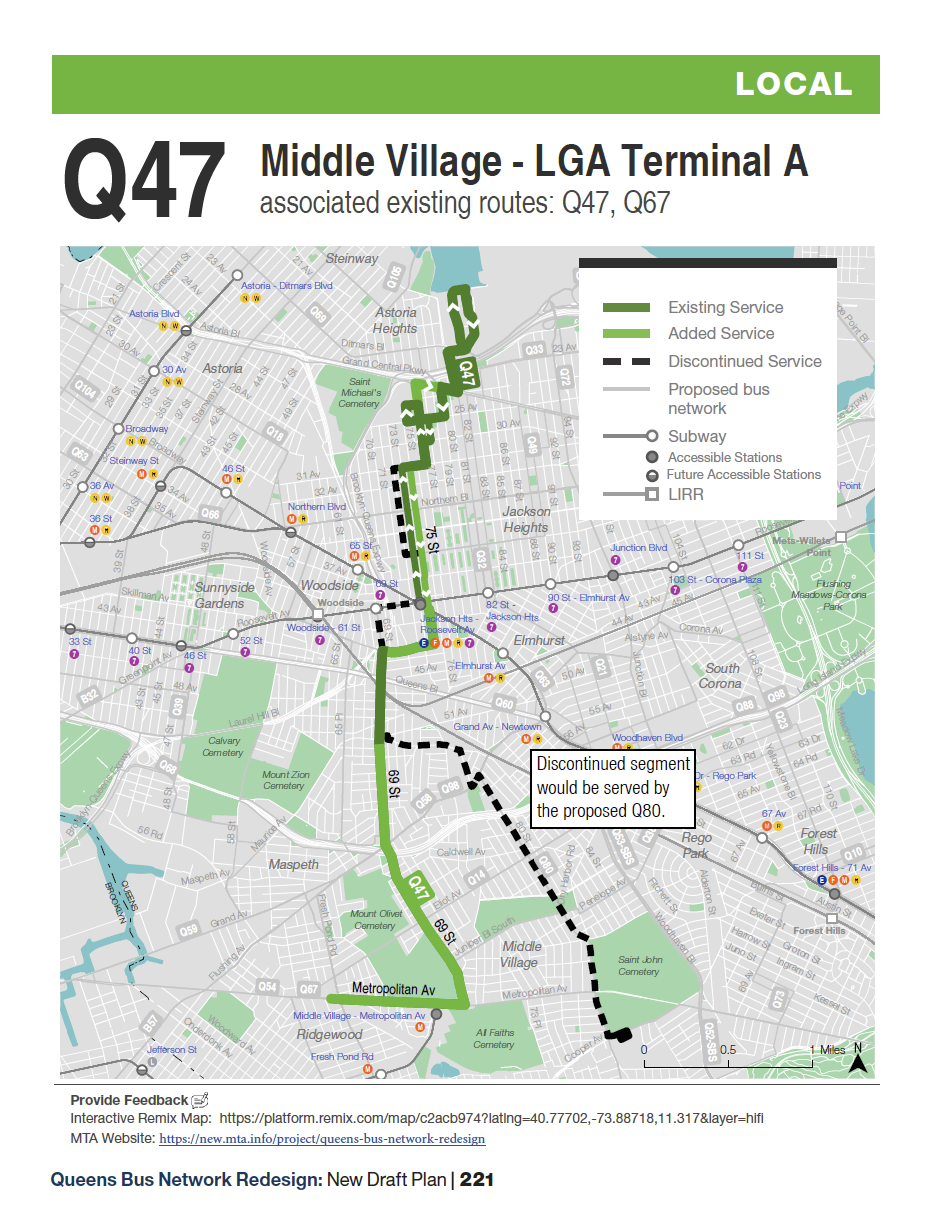

Since 2019, the MTA has been working on an overhaul of the Queens bus network. This long overdue project aims to radically change how we navigate the city. As bus lines can often be hyper-local, I will refrain from going into detail about the pros-and-cons of each. As it pertains to this corridor, the proposed Q47 realignment was a good first step, but the MTA backpedaled after locals complained. The proposal moved the Q47 line west, from 80th St ending at Atlas Park, to Metropolitan Ave and Fresh Pond, running north along 69th St to Jackson Heights and on to LGA Terminal A.

The final plan leaves far more unchanged, and adds no direct bus service between the M train at Metropolitan Ave and Jackson Heights. Instead, service on the Q58, which runs along Fresh Pond Rd and Grand Ave, is supposed to be improved. But these are two traffic choked commercial strips. Having an alternative along 69th St would have been a game changer.

Other lines such as the Q38 to Rego Park and Q39 to LIC will still have long, windy routes. Even the new Q14 service was cut back from reaching the M train at Fresh Pond, and instead will loop around up at Eliot Ave, leaving riders a half mile from the nearest subway transfer. It’s disappointing that the original concept to provide faster service to nearby subway stations has been tossed. Perhaps the only good idea that wasn’t scrapped was the Q98 SBS, which would create a Select Bus Service between Myrtle-Wyckoff and Flushing via Fresh Pond Rd and Grand Ave.

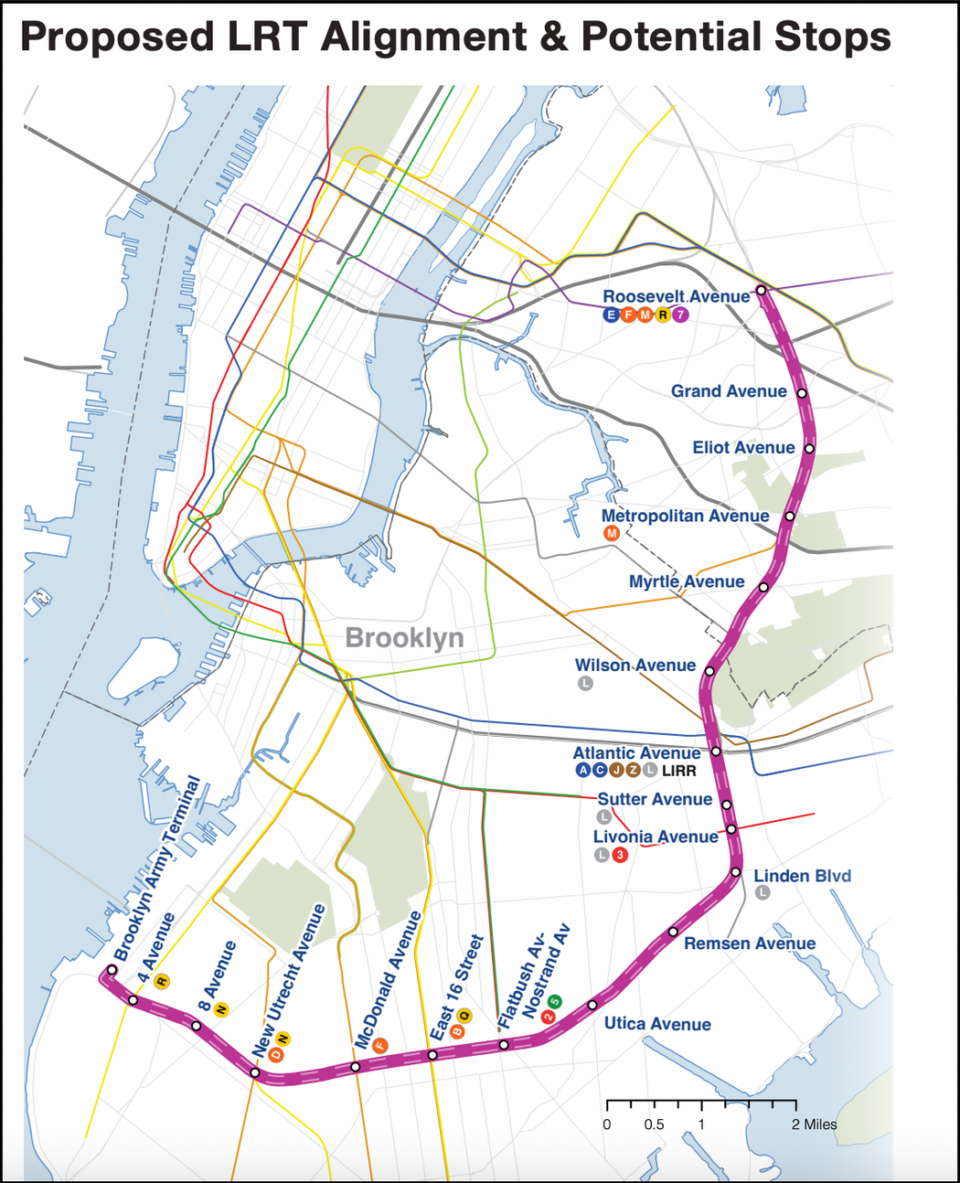

As for rail, the Regional Plan Association first proposed using the New York Connecting Railroad and Bay Ridge Branch as part of a new passenger line back in the mid 1990s. Their plans evolved into the Triboro RX, which was a light rail line from Bay Ridge to the Bronx, over the Hell Gate Bridge. In 2021, Governor Kathy Hochul proposed a modified version, the Interborough Express (IBX), that ended service at Roosevelt Ave to due to the limited capacity of the Hell Gate Bridge. This is the first official proposal for a north-south rail line through central Queens, and which would provide for a station at Metropolitan Ave and Roosevelt Ave, finally linking the M and Queens Blvd (though not directly).

At Metropolitan Ave, the MTA initially proposed requiring light rail trains run along the street, avoiding the All Faiths Cemetery. But political and community push back has, hopefully, pushed them to reconsider. I’ve written about the issue before, and when attending a public engagement event for the IBX, spoke to planners about the alternative. The number one issue brought up at that meeting was the street running.

With Governor Hochul’s pause of congestion pricing, large projects like the IBX are in doubt. While it may certainly be possible to find the funds to construct the project, these would still be competing with basic maintenance and state-of-good-repair projects. Time will tell what happens here.

Conclusion

I often hear people call certain subway extensions “low-hanging fruit”. But if low-hanging fruit has not been plucked yet, there is often a reason. For an extension of the M train north, those reasons were bad timing, bad geography, and a general preference for people to travel into Manhattan.

It’s worth pointing out that it’s really only been within the last 20 years that people have taken the outer boroughs seriously. The IBX was kicking around for a generation before MTA planners were able to focus on anything outside of Manhattan. Only since the internet has allowed us to work from home has it made sense to consider better transit between the outer boroughs as a way to move away from car travel. This is still an uphill battle, as ridership between Queens and Brooklyn has always been historically lower than ridership to Manhattan.

I’ve long been a proponent of extending the M northwards. But I would absolutely settle for better bus service between northern Brooklyn and Queens Blvd. I also think that the light rail IBX may serve this corridor well for less than a full subway extension. As an M train rider, I know that my trains aren’t all that crowded (especially compared to the L), so an M train extension may be overkill. A very real unanswered question when it comes to any transit service along this corridor is what it will do for ridership on the already congested 7 and E/F trains at Roosevelt Ave? Will more riders take the IBX to Queens to get to Midtown? I know I would. Either way, if it does eventually prove popular, this end of the IBX could be converted into an M train extension in the future.

I am not sure how the IBX will help M riders. Yes there needs to be bus service from the M terminal at Metro to Queens Blvd. As you mentioned the Q58 is long and winding. Even the Q58 Limited can take 1 ½ hrs to reach Flushing. The IBX would help those at Myrtle/Fresh Pond because it is a huge shopping district. Missing is a mention of running a service from around Western Beef at Metropolitan Ave. through an unused office building on Flushing (which can be repurposed) straight through Eliot Avenue, Fresh Pond, 80th St Atlas Mall in Glendale to Jamaica. It could help distribute people along bus routes.

Extending the M to Roosevelt Ave Jackson Heights makes plenty of sense for riders going to Downtown (if the M was rerouted back to its original configuration).

I’m curious what the travel time would be for that vs, say, taking the E, F or 7 and transferring.

Edit: A quick look at Citymapper shows that, currently, it takes 32 min from Roosevelt Ave to Chambers St via the E to the 6, while it takes 37 min from Metropolitan Ave-Middle Village to Chambers St via the M to the J. If the M was extended to Jackson Heights, and rerouted back downtown, it would be a longer trip overall.

I scanned that 1898 map and uploaded it to subway.k2nesoft.com, which later became nycsubway.org. Found a stack of them in Brooklyn College in the early 90s, where they had been used in topography classes, and asked if I could take one home. Still have the original document somewhere in my mother’s house in Brooklyn, mounted on foam board.

That’s awesome! I had a similar experience when I first moved here. I did a year at Lehman College in the Bronx, and one day while I was waiting for class to start, I noticed a large pile of papers in the corner of the room. I rummaged through and it was all maps! I still have two large 1954 maps of New Jersey and Brooklyn. They were 2 of 8, but I never found the others. I want to get them framed one day.

An extension of the M or even the IBX between Middle Village and Jackson Heights could create a pretty strong network and demand for Ridership overtime in my opinion. Couple that with the scrapped proposal for the Q47 to run straight down 69th Street (missed opportunity) could create for a really strong link. I also think that it could probably justify converting Woodhaven Blvd into an Express Station if demand proves to overwhelm Roosevelt Avenue/74th-Broadway.

Thanks for a fascinating article loaded with history that I only had the vaguest notion of! Having grown up across Myrtle Avenue from Fort Greene Park, I remember when they tore down that part of the Myrtle Avenue El. While I initially missed it a lot, later on I appreciated the free transfer to the B54 bus at Myrtle Avenue and Broadway when I was coming home from college in Manhattan which actually made it more convenient to get home at night. Which leads to my appreciation of having better design of the bus routes in the parts of Queens that the article discusses as an important way to be able to take advantage of the existing rail lines. And all of this needs to consider the drop in overall ridership following the pandemic. So many work from home now and the vacancy rate for office space in Manhattan, as I understand it, just keeps going up. This makes the question of how economical future subway expansion is at this point a difficult one.

Great post but slight inaccuracy with the historical context; the D train never ran express on the west end line when the Brown M train once operated there during rush hours

Thanks! I’ve changed it.